Hybrid Threat Assessment Through Security Analytics: A Clark–Heuer Integrative Model

(Vol. 6 No. 2, 2025. Security Science Journal)

Author:

Prof.dr Miroslav Mitrović

Faculty of Business and Law, MB University, Belgrade, Serbia

DOI: https://doi.org/10.37458/ssj.6.2.9

Review paper

Received: September 17, 2025

Accepted: November 22, 2025

Abstract: This paper develops an integrative analytical framework for assessing hybrid threats by combining Robert M. Clark’s target-centric (PMESII) approach and Richard J. Heuer Jr.’s cognitive-analytical (ACH) model. The study argues that merging systemic mapping and cognitive safeguards enhances both the external validity and internal reliability of intelligence analysis. Employing a qualitative, theory-driven design, the research contrasts the added value and operational limitations of the Clark–Heuer dual framework across Euro-Atlantic security contexts. Three illustrative cases, the Baltic States, Moldova, and the Israel–Hamas conflict, demonstrate how the model improves attribution confidence, analytical timeliness, and proportionality in hybrid threat assessment. The integration of PMESII and ACH enables real-time validation checkpoints within crisis-monitoring processes, reducing analytical error and reinforcing institutional resilience. Findings confirm that the Clark–Heuer model bridges the gap between academic theory and operational practice, offering a replicable meta-framework that strengthens analytical accountability, adaptability, and democratic legitimacy in security governance.

Keywords: Hybrid threats, intelligence analysis, Clark–Heuer model, PMESII, ACH.

Introduction

Hybrid threats, fragmented information environments, and rapid technological change increasingly undermine traditional models of risk assessment and intelligence analysis. (Mitrovic, 2018). Linear and hierarchical frameworks are no longer sufficient to address the complexity, uncertainty, and accelerated pace of today’s security environment. Contemporary challenges include cyberattacks, disinformation campaigns, transnational terrorism, and institutional subversion. These require analytical approaches that are anticipatory, adaptive, and resilient (Vu et al., 2025; Ionita, 2023). In this context, security analytics has emerged as a multidisciplinary field that combines insights from strategic studies, cognitive psychology, data science, and systems engineering. Beyond the technical processing of intelligence, security analytics provides tools for interpreting uncertainty, evaluating strategic risks, and supporting strategically robust decisions under conditions of contested narratives and information ambiguity (Clark, 2016; Heuer, 1999).

This article addresses a critical gap in the literature by integrating Clark's structural-systems approach with Heuer's cognitive-analytical framework. The Clark–Heuer framework combines systemic mapping with cognitive safeguards, aiming to enhance both the external validity of the analysis and the internal reliability of the reasoning. The integration is examined through its application to contemporary hybrid threat environments, with direct relevance to NATO and EU security institutions (Clark, 2016; Heuer, 1999).

Research Question and Hypotheses

This study asks whether the integrated Clark–Heuer framework enhances the analytical accuracy, timeliness, and proportionality of institutional responses to hybrid threats compared to existing approaches (e.g., NATO Hybrid Threats Framework, EU Hybrid Fusion Cell methodology).

H1: Integration of PMESII and ACH results in higher attribution confidence than dominant institutional frameworks.

H2: The model enables more timely and coordinated decision-making under hybrid pressure.

H3: Built-in cognitive control mechanisms mitigate the risk of over-securitisation and political misuse of hybrid threat narratives.

Theoretical Framework

The epistemological foundation of this study rests on two mutually reinforcing paradigms: Robert M. Clark’s structural-systems model and Richard J. Heuer Jr.’s cognitive-analytical model. While their emphases differ, Clark highlights external system complexity, and Heuer addresses internal cognitive processes. Both seek to enhance the validity, reliability, and sustainability of security-related decision-making (Clark, 2016; Heuer, 1999).

Clark’s target-centric approach redefines intelligence analysis as an iterative, collaborative process of system modelling. It involves collectors, policymakers, and operational actors in building a shared understanding of the target environment. Central to this approach is the PMESII framework, which captures interdependencies among political, military, economic, social, infrastructural, and informational domains, thereby enabling systemic diagnosis and scenario-based forecasting in complex security environments (Clark, 2016; Miętkiewicz, 2025; Mitrovic, 2021; Iskandarov et al., 2024).

In contrast, Heuer’s cognitive-analytical model addresses the inherent psychological limitations of human judgment. By emphasising the mitigation of cognitive biases through structured reasoning, it introduces a systematic safeguard against distortions in analysis. The Analysis of Competing Hypotheses (ACH) method operationalises this principle, testing alternative explanations in a disciplined manner and reducing the risks of premature closure, confirmation bias, and groupthink (Heuer, 1999; Jervis, 2010; Côté-Boucher, 2008).

Together, Clark’s structural mapping and Heuer’s cognitive diagnostics provide a coherent link between the target system and the analyst’s reasoning. This integration supports the creation of analytical ecosystems that are both structurally adaptive and cognitively resilient. Such capacity is vital for NATO, EU, and national institutions that operate in environments of uncertainty, multidomain interaction, and information asymmetry (Bigo, 2002; Hansen, 2006; McDonald, 2008; Iskandarov et al., 2024).

Table 1. Comparative Characteristics of Clark’s Target Centric and Heuer’s Cognitive Analytical Models

|

Analytical Dimension

|

Clark – Target-Centric (Structural) Approach

|

Heuer – Cognitive-Analytical Approach

|

Integrated Model – Dual Framework

|

|

Primary Focus

|

System-level

modelling of the external operational environment using iterative and

collaborative mapping (PMESII)

|

Internal

cognitive processes, bias recognition, and structured reasoning discipline

(ACH)

|

Simultaneous

external system mapping and internal cognitive control

|

|

Epistemological Orientation

|

Constructivist–systemic:

emphasises networked interdependencies and structural complexity.

|

Cognitive–psychological:

emphasises limitations of human judgment and the need for procedural

safeguards.

|

Critical–reflexive:

incorporates both structural context and epistemic self-awareness.

|

|

Role of Analyst

|

System

modeller and facilitator of shared situational awareness

|

Bias

mitigator, cognitive assessor, and hypothesis tester

|

Hybrid

role: systemically aware and epistemologically self-conscious

|

|

Data Interaction

|

Integration

of multi-source, multidomain data (PMESII) for scenario forecasting

|

Evaluation

of ambiguous, contradictory, and incomplete evidence

|

Data

triangulation guided by structural mapping and validated by cognitive testing

|

|

Key Methods

|

PMESII

framework, network modelling, scenario simulations

|

ACH

methodology, red teaming, assumption testing

|

Cross-referenced

scenario mapping with structured hypothesis evaluation

|

|

Strengths

|

Comprehensive

situational awareness; strategic foresight

|

Analytical

rigour; bias awareness; transparent reasoning process

|

Balanced

breadth and depth; enhanced resilience to analytic error

|

|

Limitations

|

Potential

neglect of internal cognitive distortions

|

May

overlook the systemic context of the target behaviour

|

Reduced

blind spots; mitigates both structural and cognitive vulnerabilities

|

|

Security Governance Implications

|

Enhances

anticipatory capacity in complex environments

|

Protects

decision-making from interpretive decay

|

Supports

adaptive, proportionate, and politically legitimate responses

|

Integrative Potential

When combined, Clark’s structural framework and Heuer’s introspective approach create an analytical architecture in which Clark maps the system’s external dynamics. Together, they integrate the target system and the reasoning process within a coherent and transparent analytical framework. (Marrin, 2012; Renz & Smith, 2016).

From a critical perspective, this synthesis functions as a dual safeguard. It not only strengthens the technical accuracy and reliability of analysis but also contributes to the “epistemological resilience” of institutions operating under conditions of strategic uncertainty and informational overload (Buzan et al., 1998: 213–218; Hansen, 2006). This dual resilience capacity is particularly relevant for NATO and EU institutions, which must simultaneously model complex hybrid threat environments and protect their decision-making processes from distortion, escalation, or politicisation.

By embedding both structural adaptability and cognitive vigilance, the integrative approach enables the design of analytical ecosystems that can adjust to dynamic hybrid threats while remaining self-aware of their own knowledge limitations. In practical terms, such a framework can inform the development of training curricula for analysts, the institutionalisation of red teaming procedures, and the creation of cross-sectoral analytical units. In this way, the Clark–Heuer model not only makes a conceptual contribution to security studies but also provides an actionable instrument for enhancing the resilience, accountability, and legitimacy of security governance in Euro-Atlantic institutions.

Materials and Methods

This research adopts a qualitative, theory-driven design aimed at synthesising existing analytical paradigms within security studies. Rather than empirical testing, the focus lies on comparative conceptual analysis of established theoretical models and their methodological applications across different security contexts. The primary objective is to construct a normative framework that supports integrative and reflexive practices in security analytics, while situating this integration within both epistemological and political dimensions relevant to Euro-Atlantic security governance (Bigo, 2002; Huysmans, 2006: 1-13).

Methodological Approach

The methodological approach is structured around four interrelated segments:

• Conceptual Synthesis: Drawing on foundational works in intelligence analysis and cognitive science (Clark, 2016; Heuer, 1999), the study systematically compares Clark's target-centric model with Heuer's cognitive-analytical framework. Their respective contributions and limitations are assessed in relation to NATO and EU institutional practices, acknowledging that analytical methods are inseparable from broader political and organisational structures (Bigo, 2002; Côté-Boucher, 2008).

• Typological Mapping; Modalities of security analysis (intelligence, forensic, operational) are categorised and examined in terms of their methodological and temporal characteristics. This mapping enables the assessment of not only technical capacities but also the discursive practices that define what is labelled a ‘threat,' thereby linking academic theory with policy practice (Balzacq, 2011: 39–47; McDonald, 2008; Mitrovic, 2019).

• Bias Risk Assessment: Building on insights from cognitive psychology and decision-making theory, the study identifies dominant heuristics and biases (e.g., confirmation bias, anchoring, availability heuristic) that undermine analytical validity, particularly in institutional settings under hybrid pressure (Heuer, 1999; Jervis, 2010). Recognising and mitigating these risks is presented as a requirement for institutional resilience.

• Structured Integration: A comparative matrix (Table 1) operationalises the integration of structural and cognitive paradigms by presenting their dimensions, instruments, and assumptions. That facilitates the development of a dual analytical framework that supports both systemic mapping (PMESII) and introspective cognitive control (ACH), with direct applicability for institutional procedures in NATO/EU hybrid threat analysis.

Data Sources

The analysis relies exclusively on secondary sources, including:

• Peer-reviewed literature on intelligence methodology, cognitive bias, and security decision-making;

• Strategic manuals and institutional doctrines employed in national and Euro-Atlantic security contexts;

• Contemporary academic syntheses addressing hybrid threats, systemic modelling, and anticipatory risk management (Renn, 2020; Borch & Heier, 2024; Mitrovic, 2018, 2025).

All sources are critically evaluated against the criteria of theoretical coherence, methodological rigour, and relevance for developing sustainable and politically accountable practices of security analysis.

Analytical Procedures

The research employs a matrix-based comparative analysis aligning the key features of Clark's and Heuer's models across multiple dimensions: analytical focus, reasoning logic, the role of the analyst, risk factors, and applicable tools. That enables the identification of complementarities and epistemological synergies. Particular attention is devoted to the risk of cognitive distortions in group settings and the role of structured techniques in mitigating them (Bigo, 2002; Huysmans, 2006: 37–43).

For practical applicability, the study proposes a preliminary synthesised approach that combines target modelling (systemic mapping via PMESII) with structured cognitive introspection (bias mitigation via ACH). This framework serves as both a theoretical foundation for future empirical research and a policy-relevant tool for institutional adaptation. It directly supports NATO and EU priorities in strengthening analytical resilience, transparency, and accountability in security decision-making (Côté-Boucher, 2008).

Results

The comparative analysis of Clark's target-centric model and Heuer's cognitive-analytical approach demonstrates a significant degree of functional complementarity. Clark’s work was primarily directed toward external systemic complexity, whereas Heuer concentrated on internal cognitive vulnerabilities. Although their models were developed to address different dimensions of the analytical process, their combined application suggests the potential for a more holistic and methodologically balanced framework of security analysis (Table 1). From a critical perspective, this integration can also be understood as an epistemological practice that connects structural modelling and cognitive introspection with broader questions of political legitimacy and institutional accountability (Bigo, 2002; Huysmans, 2006).

Synergistic Dimensions

The analysis identifies four key dimensions of synergy:

1. Analytical Focus: Clark's system-level modelling at the macro scale supports a comprehensive understanding of the operational environment, while Heuer's introspective orientation enhances reliability by mitigating cognitive distortions. Together, they provide analytical breadth and depth, directly addressing Bigo's (2002) argument that analytical practices both shape and legitimise security regimes.

2. Role of the Analyst: Clark frames the analyst as a modeller and facilitator of shared situational awareness, whereas Heuer highlights the analyst as a “guardian” of cognitive integrity. Their integration creates a professional profile that is simultaneously systemically aware and epistemologically self-reflexive (McDonald, 2008; Mitrovic, 2018). That has practical implications for training curricula within NATO and EU analytical units.

3. Data Processing: Clark's reliance on multidomain data integration (PMESII) complements Heuer's insistence on evaluating ambiguous or contradictory evidence. Together, they enable robust triangulation of data and defensibility of conclusions, which is particularly relevant for hybrid threat environments characterised by contested narratives (Glapiak, 2023).

4. Risk Management: Clark highlights structural risks (e.g., incomplete subsystem modelling), while Heuer emphasises psychological risks (e.g., confirmation bias, anchoring). Their joint application allows each to compensate for the other’s “blind spots,” increasing the reliability of analysis and reducing vulnerabilities in institutional decision-making (Heuer, 1999; Phythian, 2009; Mitrovic, 2021; Juberte Krūmiņa, 2024).

Analytical Instrumentation

The methodological instruments of both models rely on structured techniques but differ in scope:

• Clark employs scenario simulation, network modelling, and dynamic mapping to strengthen strategic forecasting and systemic projection. These tools support anticipatory capacity and align with NATO’s emphasis on resilience and “future-proofing” in security management (NATO 2024).

• Heuer applies ACH, red teaming, and assumption testing to ensure methodological discipline in cognitive processing. These techniques address the institutional risk of “closed epistemological loops” (Côté-Boucher, 2008; Iskandarov et al., 2024), reinforcing objectivity in politically sensitive contexts.

The integration of these tools creates a multilayered analytical architecture in which systemic representation and cognitive control coexist, each reinforcing the robustness of the other.

Functional Integration

The synthesis of Clark’s structural logic and Heuer’s cognitive tools creates an integrated framework. Clark’s systemic modelling organises the representation of threats across the political, military, economic, social, infrastructural, and informational (PMESII) domains, while Heuer’s cognitive instruments ensure discipline in the analytical process and protect against distortion or premature closure.

This integrated approach enables strategic anticipation, operational relevance, and institutional resilience, essential qualities for informed decision-making in hybrid threat environments. (Bigo, 2002; Huysmans, 2006: 23–25; McDonald, 2008). Importantly, it confirms the thesis that analytical models do not merely describe threats but also actively co-create institutional and political practices of security.

From a policy perspective, this functional integration provides NATO, the EU, and national institutions with a structured yet reflexive framework for strengthening resilience against hybrid threats. By linking systemic modelling with cognitive safeguards, the Clark–Heuer framework bridges the gap between academic theory and operational practice. It offers a replicable model for analytical training and institutional application.

In operational environments, the combined Clark–Heuer framework demonstrates practical utility through its ability to embed validation checkpoints across crisis-monitoring processes. For instance, in real-time assessments of hybrid activities—such as cyber-enabled disinformation or coordinated social unrest—the PMESII mapping stage serves to rapidly delineate affected systemic domains (e.g., information, infrastructure, or economic stability). This step is immediately followed by an ACH-based validation checkpoint, where competing hypotheses about causality or attribution are tested using updated intelligence inputs. If an emerging signal contradicts earlier assumptions, the analyst re-enters the PMESII loop to adjust scenario modelling accordingly. This iterative interaction between systemic mapping and cognitive verification not only strengthens situational awareness but also prevents analytical overconfidence under time pressure.

Practically, these validation checkpoints can be institutionalized as part of crisis-monitoring dashboards or early-warning mechanisms, allowing analysts to recalibrate judgments at predefined intervals (e.g., every two hours during hybrid escalation). Such procedural integration illustrates how the model translates conceptual robustness into actionable workflow, thereby reducing analytic latency and enhancing decision proportionality during hybrid crises.

Discussion

The findings confirm the need to transcend monodisciplinary and linear analytical frameworks in contemporary security analysis. As emphasised by Bigo (2002) and Huysmans (2006), today’s security landscape is not defined by traditional frontlines but by hybrid forms of confrontation that blur the boundaries between war and peace, state and non-state actors, and physical and informational domains (Mitrovic, 2019). Such conflicts, as Mitrovic (2025) notes, operate through the combined use of military, political, informational, and economic instruments aimed at eroding state capacities and social cohesion without necessarily resorting to overt kinetic escalation. In this context, the epistemological and functional integration of systemic structural modelling (Clark, 2016) and cognitive bias mitigation (Heuer, 1999) represents not only a technical innovation but also a paradigmatic shift in the organisation, execution, and interpretation of analytical processes.

Epistemological–Functional Integration

Within the framework of critical security studies, the Clark–Heuer model may be viewed as a dual epistemological matrix. Structural validity (Buzan et al., 1998: 29–31; Mitrovic, 2019) refers to the ability to model, contextualise, and anticipate complex threat vectors, particularly when they span multiple domains and interact in non-linear ways. Cognitive reliability entails recognising and managing the internal vulnerabilities of the analytical process, including biases, institutional path dependencies, and the risks of groupthink (Heuer, 1999; Jervis, 2010).

Operationalised in practice, Clark's systemic approach provides an adaptive representation of the external threat environment, while Heuer's introspective techniques safeguard the internal integrity of analytical reasoning. This reflexive methodological practice (Hansen, 2006) connects the material and discursive dimensions of security knowledge. Importantly, such integration is especially significant in hybrid conflicts, where threats do not manifest solely through discrete events but through cumulative and hardly attributed processes of erosion and destabilization. (Mitrovic, 2025).

Application in Hybrid Conflicts

Hybrid adversaries deliberately exploit seams between sectors, institutions, and perceptions to achieve disproportionate effects with limited attribution. Fragmented intelligence pictures, manipulative narratives, and time-sensitive ambiguities challenge both the speed and accuracy of responses (Côté-Boucher, 2008). Without a model that combines external systemic mapping and internal cognitive discipline, institutional decision-making risks distortion, escalation, or deviation from long-term strategic objectives. The Clark–Heuer framework provides a corrective mechanism, reinforcing both analytical accuracy and resilience to political instrumentalisation of hybrid narratives.

Normative Implications and Recommendations

From a policy perspective, the Clark–Heuer framework can serve as a meta-framework for strengthening analytical resilience in NATO, the EU, and national institutions. Specifically, it supports:

• The design of analytical protocols that integrate structural mapping (PMESII) with cognitive discipline (ACH);

• The development of training programs that embed bias awareness and systems thinking in analyst education.

• The institutionalization of verification mechanisms, such as red teaming, structured challenge sessions, and scenario-based reasoning, for high-risk decisions (Hicks et al., 2023).

The model aligns with current priorities that emphasize durable decision-making in strategic fields, including energy, defense, cybersecurity, and public health. In those sectors, misjudging hybrid threats can trigger cascading failures, reputational erosion, or systemic collapse (Mitrovic, 2021; Glapiak, 2023; Juberte Krūmiņa, 2024).

Empirical Illustrations – Case Applications

The analysis of three hybrid conflict cases, such are the Baltic States (2023), Moldova (2023), and the Israel–Hamas conflict (2021–2022), demonstrates the practical value of the Clark–Heuer framework. In each scenario, the combination of PMESII structural mapping and ACH cognitive validation enabled two-step verification of findings and reinforced institutional resilience against hybrid threats.

• Baltic States (2023). The model increased attribution confidence by ruling out spontaneous unrest or criminal opportunism and confirming a state-sponsored hybrid campaign. Despite improved scenario mapping, inter-agency coordination gaps limited timeliness.

• Moldova (2023); The framework confirmed the external orchestration of destabilisation, allowing for pre-emptive countermeasures. The dual approach accelerated decision-making and preserved analytical objectivity in a polarised political environment.

• Israel–Hamas (2021–2022); The model enabled differentiation between grassroots activism, criminal opportunism, and strategic hybrid aggression. ACH safeguarded against threat inflation, ensuring proportional responses under political and public pressure.

Across all cases, the Clark–Heuer framework enhanced attribution accuracy (H1), improved timeliness despite some coordination constraints (H2), and consistently mitigated the risks of over-securitization and the political exploitation of hybrid narratives (H3).

Evaluating the Clark–Heuer Model Across Hybrid Threat Scenarios

A comparative review of the three case studies demonstrates the analytical utility and adaptability of the Clark–Heuer integrative model in addressing hybrid threats across diverse geopolitical and operational settings. In each case, the combination of PMESII structural mapping and ACH cognitive validation enhanced analytical rigour and reinforced institutional responses (Mitrovic, 2025; Miętkiewicz, 2025; Praks, 2024). The findings confirm that sustainable hybrid threat assessment requires not only systemic modelling but also cognitive safeguards embedded in institutional practice.

Structural Mapping Across Cases (Clarkian Analysis)

Across all scenarios, Clark’s PMESII framework provided a systemic representation of hybrid threat dynamics:

• Baltics (2023): Analysts identified multidomain threats, including DDoS attacks on public portals (infrastructure), orchestrated narratives targeting ethnic communities (information), and economic destabilisation through manipulation of the energy market. These findings correspond to NATO CCDCOE's observations on converging hybrid vectors in the Baltic region (Miętkiewicz, 2025).

• Moldova (2023): Supported by the EU Hybrid Fusion Cell and Hybrid CoE, the Moldovan SIS revealed a coordinated campaign of protest mobilisation, cyber intrusions, and media manipulation aimed at undermining EU integration and fragmenting the political narrative (Praks, 2024; Pociumban, 2023).

• Israel–Hamas (2021–2022): Israel faced cyber-kinetic hybrid operations combining disinformation, phishing, and deepfake materials with physical attacks on critical infrastructure. Attribution linked these actions to Iranian proxy entities (Microsoft Threat Intelligence, 2024; Ram & Antebi, 2023; Vu et al., 2025).

Cognitive Validation Across Cases (Heuerian Analysis)

Heuer’s ACH methodology proved decisive in narrowing attribution pathways and filtering deceptive indicators:

• Baltics: ACH eliminated hypotheses of spontaneous unrest or criminal disinformation, confirming an externally directed hybrid campaign (Miętkiewicz, 2025).

• Moldova: Structured red teaming and assumption checks exposed external orchestration, reducing the risk of misattribution amid internal political polarization (Praks, 2024).

• Israel: ACH differentiated between grassroots activism, criminal opportunism, and state-linked aggression, confirming attribution through convergent forensic and narrative analysis (Microsoft Threat Intelligence, 2024; Ram & Antebi, 2023).

Indications for Model Development

The comparative cases highlight refinements needed for operationalising the Clark–Heuer framework:

• Baltics: ACH effectiveness increases when PMESII modelling is supplemented with real-time OSINT integration, suggesting the need for standardised open-source exploitation protocols.

• Moldova: PMESII modelling proved less effective without diplomatic and international intelligence inputs, indicating the necessity of formal inter-institutional linkages.

• Israel: ACH remained functional under operational stress but suffered from delays in inter-agency coordination, underscoring the need for accelerated coordination mechanisms in high-tempo environments.

The comparative analysis confirms that the Clark–Heuer model provides a double assurance for institutions facing hybrid threats: systemic mapping enhances anticipatory capacity, while cognitive safeguards mitigate the risks of distortion and politicization. From a policy perspective, the model provides NATO, the EU, and national institutions with a replicable framework for enhancing resilience, accountability, and legitimacy in decision-making under hybrid pressures.

The integrative architecture not only improves attribution and timeliness but also supports proportional and democratically legitimate responses. By combining analytical strictness with commitments to transparency and accountability, the Clark–Heuer framework provides a sustainable model of security governance suited to the challenges of hybrid conflict.

Table 2. Comparative assessment of hypotheses across three hybrid threat scenarios using the Clark–Heuer integrated model

|

Case

|

H1 Supported?

|

H2 Supported?

|

H3 Supported?

|

Key Variables

|

|

Baltic States

|

Yes

|

Partial

|

Yes

|

Inter-agency coordination,

real-time OSINT integration

|

|

Moldova

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

EU coordination, NGO financing

oversight

|

|

Israel–Hamas

|

Yes

|

Partial

|

Yes

|

Cyber-defence readiness, public

diplomacy integration

|

Synthesis: A Dual-Lens for Sustainable Threat Assessment

The three case studies confirm that the integration of the Clark–Heuer model provides a dual analytical architecture that enables:

• Strategic modelling of external threat systems (via PMESII);

• Cognitive control over internal analytical distortions (via ACH);

• A sustainable and resilient foundation for institutional decision-making under conditions of uncertainty and multidomain pressure.

Clark's component maps the dynamic ecological systems of threats, while Heuer's component safeguards judgment from degradation. In combination, they enable the anticipation of multidomain threats, credible attribution, and the formulation of proportional responses, ranging from public communication and cyber defence reinforcement to legislative adjustments and international diplomatic signalling. (Mitrovic, 2025; Hansen, 2006).

Compared with existing institutional frameworks, such as the NATO Hybrid Threats Framework (NATO, 2024) and the methodological approach of the EU Hybrid Fusion Cell (Lasoen, 2022), the Clark–Heuer model provides a unique advantage in the form of dual resilience capacity. While NATO's framework emphasises the identification of multidimensional hybrid vectors, and the EU Hybrid Fusion Cell focuses on cross-sectoral intelligence exchange, both engage less systematically with mitigating cognitive distortions in the analytical process.

The integrative model presented in this study fills this gap by combining PMESII systemic mapping (ensuring external validity of assessments) with ACH cognitive control (ensuring internal reliability of reasoning). This dual architecture not only enhances attribution quality but also increases resilience to time pressure, perception manipulation, and political instrumentalisation of hybrid threats. In this way, the Clark–Heuer approach surpasses linear models of the intelligence cycle, providing a reflexive analytical structure that is applicable in real-time and compatible with democratic norms and transparency requirements (Mitrovic, 2025; NATO, 2024; Lasoen, 2022; Weissmann, 2025).

Theory Feedback Loop

The comparative analysis of the cases also highlights refinements for the theoretical architecture of the Clark–Heuer framework.

• In the Baltic scenario, high-quality OSINT proved decisive in validating ACH outcomes, suggesting that open-source exploitation should be operationalised as a core analytical function (Miętkiewicz, 2025).

• In the Moldovan case, PMESII modelling was less effective without diplomatic intelligence inputs, underscoring the need for inter-institutional liaison protocols to reflect the full spectrum of political dynamics (Praks, 2024; (Pociumban, 2023).

• In the Israel–Hamas conflict, ACH remained useful under operational pressure but was hindered by inter-agency coordination delays, underscoring the need to embed rapid synchronisation mechanisms into cognitive validation (Microsoft Threat Intelligence, 2024; Ram & Antebi, 2023).

These insights reinforce that sustainable hybrid threat assessment requires not only structural–cognitive integration but also adaptive institutional linkages, cross-domain intelligence fusion, and procedural agility in high-pressure environments (Mitrovic, 2021; Ionita, 2023).

Conclusion

As hybrid threats continue to evolve and adapt, security institutions must institutionalise analytical architectures that combine systemic thinking, cognitive vigilance, and anticipatory logic (Mitrovic, 2025). Such models, as emphasized in critical security studies (Bigo, 2002; Huysmans, 2006), are not only technical instruments but also epistemological and political mechanisms that shape how threats are conceptualized and how responses are legitimized. Only through such integration can analytical ecosystems remain both functionally adaptive and intellectually accountable, ensuring that decision-making under uncertainty does not succumb to distortion, escalation, or paralysis (Mitrovic, 2025; Glapiak, 2023; Juberte Krūmiņa, 2024).

The comparative analysis of three hybrid threat scenarios, demonstrates that the Clark–Heuer model enhances attribution accuracy, improves timeliness under hybrid pressure, and mitigates the risks of over-securitization. The model achieves this by uniting:

1. Structural insights derived from PMESII systemic mapping (Clark);

2. Cognitive validation of hypotheses through ACH methodology (Heuer);

3. Integrated institutional responses that balance analytical rigour with proportionality and democratic accountability.

This synthesis demonstrates that integrated modelling is crucial for providing balanced and comprehensive responses in contexts characterized by multidomain, complex, and rapidly evolving threats. It also highlights the need for hybrid threat assessment to move beyond purely technical modelling and develop a reflexive framework that connects the material and discursive dimensions of security. (McDonald, 2008; Hansen, 2006).

The Clark–Heuer framework integrates two previously distinct domains: structural systems analysis and cognitive bias control into a unified, practical model. Unlike NATO and EU approaches, which often treat these dimensions in isolation, this model provides an iterative process that adapts to evolving hybrid threats while protecting analytical integrity. For NATO, the EU, and national institutions, such a model provides a replicable and sustainable foundation for decision-making that is both operationally resilient and democratically legitimate.

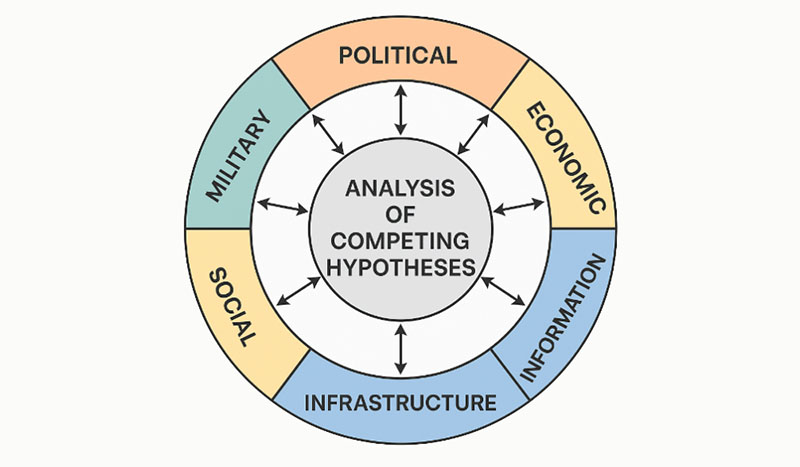

Figure 1: The Clark–Heuer combined model

As the visual representation demonstrates, the PMESII framework forms the outer ring encompassing six structural dimensions: political, military, economic, social, infrastructural, and informational. Thus ensuring a comprehensive mapping of complex adaptive systems affected by hybrid operations. At the centre lies the Analysis of Competing Hypotheses (ACH), which systematically tests causal assumptions, identifies weak evidence, and recognises cognitive biases that may distort analytical judgment (Heuer, 1999; Jervis, 2010).

Bidirectional linkages between PMESII and ACH create a feedback loop: systemic modelling generates substantive hypotheses for evaluation, while ACH provides probabilistic conclusions that can redefine analytical focus. This iterative interaction fosters methodological discipline, enhances attribution reliability, and supports proportionate policy formulation (Hansen, 2006; McDonald, 2008).

Key Findings:

1. Hybrid threats require hybrid methods; Conventional linear models fail to capture the complex, adaptive, and often concealed nature of hybrid activity. The Clark–Heuer framework bridges this gap by integrating systemic modelling and cognitive safeguards (Mitrovic, 2025).

2. Structural modelling enhances anticipatory capacity; PMESII mapping enabled early warning, systemic diagnosis, and scenario planning, as shown in the Baltic and Moldovan cases (Miętkiewicz, 2025).

3. Cognitive discipline preserves analytical integrity; ACH reduces the risks of premature closure, groupthink, and confirmation bias, thereby reinforcing objectivity in politically charged environments (Côté-Boucher, 2008).

4. Integrated analysis enables a calibrated response; The dual model supports timely, proportionate interventions, ranging from cyber defense to legislative reform and diplomatic signalling (Praks, 2024; (Pociumban, 2023).

Beyond methodological innovation, the Clark–Heuer model addresses normative risks in hybrid threat assessment. Without safeguards, securitization can be misused for political manipulation (Buzan et al., 1998: 208–218; Bigo, 2002). The model strengthens resilience while enhancing democratic accountability through transparency in assumptions, structured testing of alternatives, and documentation of reasoning.

To institutionalise analytical sustainability, NATO, the EU, and national security actors should:

• Adopt a dual-framework doctrine integrating PMESII and ACH;

• Introduce training programmes on systems thinking, ACH, and bias recognition;

• Embed reflexive mechanisms (red teaming, challenge sessions, multi-perspective reviews) into high-risk assessments;

• Establish cross-sectoral analytical cells that link security, economic, cyber, and social expertise (Onwubiko & Ouazzane, 2022).

Future research should explore:

• Empirical validation of the framework in non-state conflicts, private sector applications, and international crisis simulations;

• Comparative evaluation of integrated vs. non-integrated teams in hybrid threat exercises;

• Technological augmentation of ACH and PMESII with AI-driven tools (e.g., Bayesian inference, PMESII–ML integration);

• Ethical and procedural safeguards for using structured analysis in coercive or anticipatory policy instruments.

The Final Remark is that in an era shaped by contested truths, algorithmic manipulation, and transnational subversion, sustainable security governance begins with sustainable analysis. The Clark–Heuer framework offers not only a methodology but also a discipline of reasoning that enables institutions to navigate uncertainty with clarity, accountability, and strategic foresight. By integrating structural mapping with cognitive safeguards, the model reduces the costs of analytical error, prevents disproportionate responses, and embeds resilience and democratic legitimacy into security governance (Mitrović, 2025).

References

- Balzacq, T. (2010). Securitization theory: How security problems emerge and dissolve. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203868508

- Bigo, D. (2002). Security and immigration: Toward a critique of the governmentality of unease. Alternatives: Global, Local, Political, 27 (1_suppl), 63–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/03043754020270S105

- Borch, O. J., & Heier, T. (Eds.). (2024). Preparing for hybrid threats to security: Collaborative preparedness and response (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781032617916

- Buzan, B., Wæver, O., & de Wilde, J. (1998). Security: A new framework for analysis. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Clark, R. M. (2016). Intelligence analysis: A target-centric approach (5th ed.). CQ Press/SAGE Publications.

- NATO (2024, June). Hybrid threats and hybrid warfare: Reference curriculum. Brussels: NATO Headquarters https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/2024/7/pdf/241007-hybrid-threats-and-hybrid-warfare.pdf

- Côté-Boucher, K. (2008). The diffuse border: Intelligence-sharing, control and confinement along Canada’s smart border. Surveillance & Society, 5(2), 142–165. https://doi.org/10.24908/ss.v5i2.3432

- Glapiak, A. (2023). Implications of the war in Ukraine for the strategic communication system of the Polish Ministry of National Defence. Security and Defence Quarterly, 43(3), 22–45. https://doi.org/10.35467/sdq/173070

- Hansen, L. (2006). Security as practice: Discourse analysis and the Bosnian war. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203236338

- Heuer, R. J., Jr. (1999). Psychology of intelligence analysis. Washington, DC: Center for the Study of Intelligence, Central Intelligence Agency.

- Hicks, M.-L., Guest, E., Whittlestone, J., Ohrvik-Stott, J., Zakaria, S., Ang, C., Wade, I., & Gunashekar, S. (2023). Exploring red teaming to identify new and emerging risks from AI foundation models: Summary workshop report (Workshop Report No. CFA3031-1). RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/conf_proceedings/CFA3000/CFA3031-1/RAND_CFA3031-1.pdf

- Huysmans, J. (2006). The Politics of Insecurity: Fear, Migration and Asylum in the EU (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203008690

- Ionita, C. (2023). Conventional and hybrid actions in the Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Security and Defence Quarterly, 44(4), 5–20. https://doi.org/10.35467/sdq/168870

- Iskandarov, K. I., Gawliczek, P. & Soboń, A. (2024). Violation of territorial integrity as a tool for waging long-term hybrid warfare (against the backdrop of power games in the South Caucasus region). Security and Defence Quarterly, 45(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.35467/sdq/174507

- Jervis, R. (2010). Why intelligence fails: Lessons from the Iranian Revolution and the Iraq War. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Juberte Krūmiņa, L. (2024). Role of the private sector within Latvia’s strategic defence documents: Dimensions of psychological resilience and strategic communication. Security and Defence Quarterly, 47(3), 19–37. https://doi.org/10.35467/sdq/186719

- Lasoen, K. (2022). Realising the EU hybrid toolbox: Opportunities and pitfalls. Policy Brief. The Hague: Clingendael Institute. https://www.clingendael.org/sites/default/files/2022-12/Policy_brief_EU_Hybrid_Toolbox.pdf

- Marrin, S. (2012). Evaluating the Quality of Intelligence Analysis: By What (Mis) Measure? Intelligence and National Security, 27(6), 896–912. https://doi.org/10.1080/02684527.2012.699290

- McDonald, M. (2008). Securitization and the Construction of Security. European Journal of International Relations, 14(4), 563-587. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066108097553

- Microsoft Threat Intelligence. (2024, February 26). Iran surges cyber-enabled influence operations in support of Hamas. Microsoft Security Insider. https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/security/security-insider/threat-landscape/iran-surges-cyber-enabled-influence-operations-in-support-of-hamas

- Miętkiewicz, R. (2025). Hybrid threats in the Baltic Sea: The results of analysis of countermeasure options. Terrorism – Studies, Analyses, Prevention (Special Issue), 35–70. https://doi.org/10.4467/27204383TER.25.014.21517

- Mitrovic, M. (2018). The Balkans and non-military security threats – quality comparative analyses of resilience capabilities regarding hybrid threats. Security and Defence Quarterly, 22(5), 20–45. https://doi.org/10.5604/01.3001.0012.7224

- Mitrovic, M. (2019). Influence of global security environment on collective security and defence science. Security and Defence Quarterly, 24(2), 5–20. https://doi.org/10.35467/sdq/106088

- Mitrovic, M. (2021). Assessments and foreign policy implementation of the national security of Republic of Serbia. Security and Defence Quarterly, 34(2), 7–19. https://doi.org/10.35467/sdq/135592

- Mitrovic, M. (2025). Invisible fronts: Hybrid warfare and the future of conflict. Columbia, SC: Independently published.

- Onwubiko, C., & Ouazzane, K. (2022). Multidimensional cybersecurity framework for strategic foresight (arXiv preprint arXiv:2202.02537). arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2202.02537

- Phythian, M. (2009). Intelligence Analysis Today and Tomorrow. Security Challenges, 5(1), 67–83. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26459162

- Praks, H. (2024 May). Hybrid CoE Working Paper 32: Russia’s hybrid threat tactics against the Baltic Sea region: From disinformation to sabotage. European Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats. https://www.hybridcoe.fi/publications/hybrid-coe-working-paper-32-russias-hybrid-threat-tactics-against-the-baltic-sea-region-from-disinformation-to-sabotage

- Ram, Y., & Antebi, L. (2023, November 5). Deep fake in Swords of Iron: A battle for public opinion (Insight No 1779). Institute for National Security Studies. https://www.inss.org.il/publication/war-deep-fake

- Renn, O. (2020). New challenges for risk analysis: systemic risks. Journal of Risk Research, 24(1), 127–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2020.1779787

- Renz, B., & Smith, H. (2016). Russia and hybrid warfare: Going beyond the label. Aleksanteri Papers No. 1/2016. Kikimora Publications, University of Helsinki. https://helda.helsinki.fi/server/api/core/bitstreams/9514b166-0249-42a4-a408-9195e7d32292/content

- Rid, T. (2020). Active measures: The secret history of disinformation and political warfare. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Pociumban, A. (2023, October 31). Moldova’s response to hybrid attacks: A learning-by-doing strategy (Campaigning Against Hybrid Threats Paper Series). The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies. https://www.hcss.nl/report/moldovas-response-to-hybrid-attacks

- Vu, A. V., Hutchings, A., & Anderson, R. (2025). Yet another diminishing spark: Low-level cyberattacks in the Israel–Gaza conflict (arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.15592). arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2504.15592

- Weissmann, M. (2025). Future threat landscapes: The impact on intelligence and security services. Security and Defence Quarterly, 49(1), 40–57. https://doi.org/10.35467/sdq/197248