Author: Antonia Dimou

Abstract

Overcoming gender bias has been increasingly important to counter ongoing threats to national and international security. The article focus on the institutional framework that exists for the participation of women in peace and security at the United Nations and NATO levels. It expands to the success story of women’s inclusiveness in the Jordanian armed forces, as well as to the challenges of health security, and concludes with a set of concrete policy recommendations.

Keywords: women, peacebuilding, conflict resolution, human dignity, human security, Jordanian Armed Forces, UNSC 1325, Jordan, NATO, women’s empowerment

THE INTERNATIONAL CONTEXT

Women’s role is critical for resolving conflicts, fostering peace, promoting reconciliation,

and safeguarding national security. No country can maintain national security if half of its population is left behind. National security or national defense engulfs military and non-military dimensions like security from terrorism, economic, health, and energy security. One should not ignore national security risks with most prevailing violent non-state actors and the effects of natural disasters. The role of women in peacekeeping, peace-making, and peacebuilding and their overall inclusion in the decision-making of conflict resolution and post-conflict reconciliation processes can contribute to the maintenance of international peace and security. Equal representation however is not yet a reality, especially at senior levels of decision making even though women are increasingly present in defense and foreign affairs and hold positions in government and the military establishment around the world.

International organizations have put in place all instruments to ensure the vital participation of women in peace and security. The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 1979 requires States in article 7 to ensure that women are guaranteed the rights to vote, to hold public office, and to exercise public functions . This includes equal rights for women to represent their countries at the international level according to article 8 of the Convention. The United Nations Security Council adopted on 31st October 2000 Resolution 1325 that calls for a more gender-representative and responsive security sector thus having launched the Women, Peace, and Security agenda . The resolution reaffirms the important role of women in the prevention and resolution of conflicts, peace negotiations, peacebuilding, peacekeeping, humanitarian response, and post-conflict reconstruction and stresses the importance of their equal participation and full involvement in all efforts for the maintenance and promotion of peace and security. It also urges all actors to increase the participation of women and incorporate gender perspectives in all United Nations peace and security efforts.

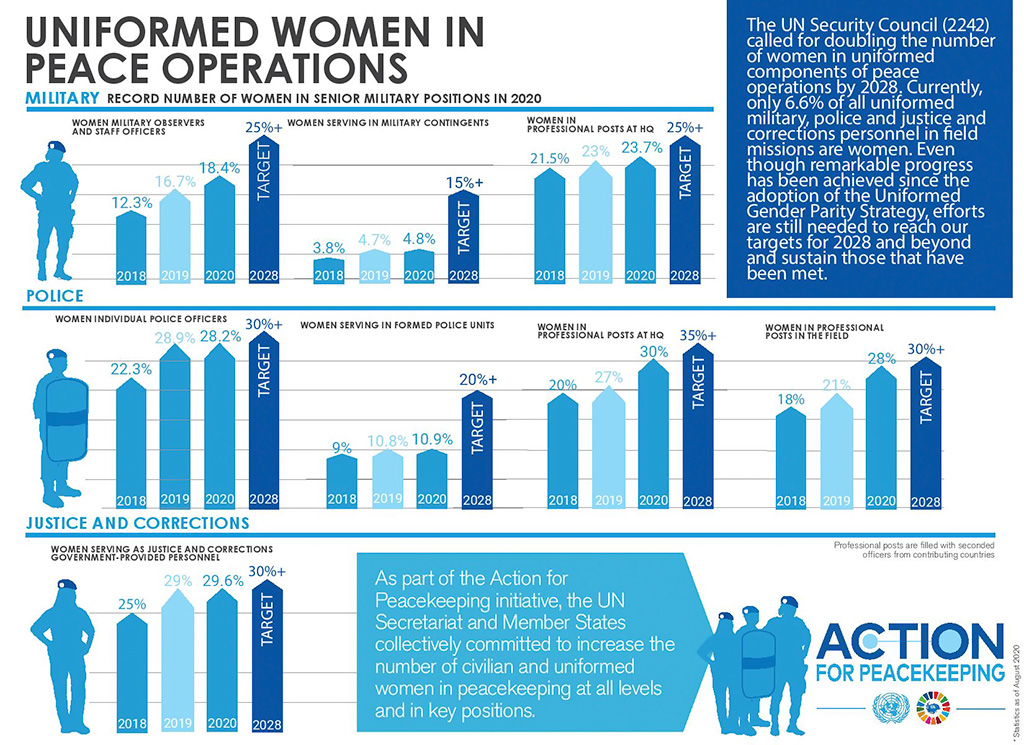

Ten additional resolutions followed since 2000 revising the Women, Peace and Security agenda like Resolution 1820 on sexual violence during wars, resolution 1888 that mandates peacekeeping missions to protect women, girls from sexual violence in armed conflict, and others (1889, 1960, 2106, 2122, 2422, 2467 and 2493). The UN Security Council Resolution 2242 calls for doubling the number of women in uniformed components of peace operations by 2028. Currently, only 6.6% of all uniformed military, police, and justice and corrections personnel in ¬field UN missions are women. Even though remarkable progress has been achieved since the adoption of the Uniformed Gender Parity Strategy, efforts are still needed to reach the UN targets for 2028. For example, as it can be seen in Table 1 below, the target for women military observes and staff officers are from 18,4% in 2020 to reach 25% in 2028; the target for women serving in military contingents is from 4,8% in 2020 to reach 15% in 2028; the target for women in professional posts in military headquarters is from 23,7 % in 2020 to reach 25% in 2028 .

TABLE 1: Uniformed Women in Peace Operations

Source: (United Nations)

It is also noteworthy that women have extremely limited involvement in peace-making processes. The UN looked at 24 peace processes in 2012 and saw women as only 2.5% of the signatures, 5.5% of witnesses, and 7.6% of negotiators . A study of different approaches to Resolution 1325 found that some countries have been successful in including women in peace processes but have not changed the basic way in which they conduct these negotiations, while others have more successfully changed working models even while failing to include women in the process .

NATO’s WOMEN, PEACE AND SECURITY POLICY

According to the original UN Resolution 1325, international security organizations and countries strive to change the traditional conceptual framework in which “security” tends to be a man’s narrative.

NATO’s approach to the Women, Peace, and Security agenda is framed around the principles of integration, inclusiveness, and integrity. In 2018, NATO endorsed the revised Women, Peace, and Security policy agenda, while NATO Secretary-General appointed a Special Representative for Women, Peace, and Security serving as the high-level focal point for NATO’s work in this domain.

The 50-nation Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council (EAPC) which is a multilateral forum for dialogue and consultation on political and security-related issues among Allies and partner countries have agreed on the Women, Peace and Security policy in addition to eight partners beyond the Council’s (EAPC) framework that have associated themselves with the policy, namely Afghanistan, Australia, Israel, Japan, Jordan, New Zealand, Tunisia, and the United Arab Emirates.

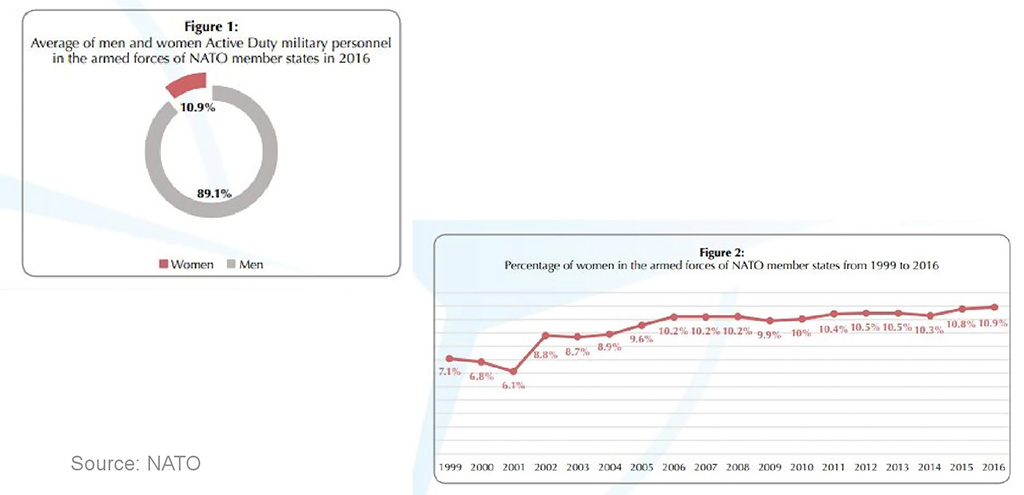

As it can be seen in Table 2 below (Figures 1 &2), only a few women deployed on NATO member states’ Common Security and Defense Policy (CSDP) missions and operations from 1996 to 2016, while in 2016 the average of women active-duty military personnel in the armed forces of NATO member states was 10,9 percent. This reality has prompted NATO to embrace the Women, Peace, and Security agenda with the aim to integrate gender perspectives in NATO from policy, planning, and training to missions and operations.

TABLE 2: Percentage of Women in the Armed Forces of NATO member states

Through their cooperation programs with NATO, Allies and partners are encouraged to support the implementation of the Women, Peace, and Security agenda through the development of education and training activities, the inclusion of a gender perspective in the curriculum of NATO Training Centres and Centres of Excellence. The Nordic Centre for Gender in Military Operations is hosted by Sweden, one of NATO’s partners .

In addition, NATO improves gender balance in its civilian and military structures and encourages Allies and partners to do the same. Gender Advisors are appointed across NATO’s military structures and in all operations and missions. The first NATO Gender Advisors were deployed in 2009 to NATO’s two Strategic Commands, and to the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) in Afghanistan that was replaced in 2015 by the Resolute Support Mission (RSM). Men and women operate at strategic and operational levels, and their Commanders are responsible for the integration of gender perspectives into planning, execution, and evaluation.

To integrate women’s voices within and outside NATO, the defense organization has initiated a project called “Women’s Defence Dialogues”, which is practically a platform for women so that their voices are heard across intersectional spectrums about defense and security. NATO intends to host these dialogues in each allied and partner country.

Equally important, NATO changes the way it traditionally works by exploring the gender dimensions of terrorism, recognizing that women are not only victims of terror but also powerful actors who can prevent or perpetrate terrorist actions. For example, women of the Islamic State (ISIL) most of whom live in camps in Syria, Iraq, and Libya could pose a significant threat to these countries and to the broader global community. Deradicalization researchers state that a significant number of ISIL women continue to indoctrinate their children with the group’s ideology and tell them that they must avenge the deaths of their fathers by carrying out attacks when they grow up.

Of course, there are many women who were forced to join ISIL and do not subscribe to its ideology. This reality surfaces the necessity for more women to join military intelligence and counterterrorism operations. At the political level, it is evident that governments must develop gender-specific deradicalization/integration programs which reflect the different roles played by different women within terrorist organizations. UN agencies should also work with local governments to develop high-quality educational curricula and extracurricular activities to help women resist radicalization and to enable them to find meaningful work in their home countries.

WOMEN’S INCLUSIVENESS IN THE JORDANIAN ARMED FORCES

The 2005 Amman bombings is another example where an Iraqi female participated in the terrorist attacks having stressed the need for more women to join the Jordanian counterterrorism and intelligence forces. In fact, Jordan is a NATO partner and UN member country that has advanced the Women, Peace, and Security agenda expanding opportunities for women’s participation in the Jordanian armed forces. Throughout 2006 and 2016, recruitment and training of more women in the armed forces have been successful in pursuance with a National Action Plan (NAP) to implement UNSCR 1325 and subsequent resolutions which were drafted by the Jordanian National Commission for Women (JNCW) . Recruitment success has partly been evidenced by the fact that female applications have exceeded the needs of Jordan’s armed forces.

According to a Jordanian national statistical report, as of 2018, there were approximately 4,800 women in uniform out of which around 1,200 are officers, 2,400 are servicewomen and 1,260 are civilians. These figures represent almost 3 percent of all of the kingdom’s military forces . Jordanian women have access to the Air Force, the Military Police, the Royal Guard Protection Unit, and Military Intelligence. Jordanian women have reached the ranks of brigadier general in the Armed Forces General Command and major general in the Royal Medical Services. Women receive all specialized training programs identical to men since 2006.

In addition, the Directorate of Women’s Military Affairs established in 1995 has created the first female company for special security tasks through which servicewomen receive the necessary training to carry counterterrorism and crisis management operations, protect personnel, and provide security at airports and conferences. Their training includes shooting, raiding, and evacuating hostages by sea, air, and land. In 2015, the female company for special security tasks was the first Arab female armed forces company to participate in the 15th NATO Days in Ostrava, the largest security show in Europe .

Jordanian servicewomen in the military, police, and civil defense also participate in the United Nations Peacekeeping operations and other NATO missions like for example in Afghanistan where Jordanian servicewomen took part in Task Force 222, Task Force 333, and other NATO International Security Assistance Force missions as trainers . Despite women’s contribution in peacekeeping operations, the target of 12 percent for women’s participation has not been achieved yet.

The success story of Jordan in recruiting female officers lies in that the Directorate of Women’s Military Affairs takes into consideration cultural and religious uniqueness affirming that women who serve in the military do not have to jeopardize cultural and traditional norms. For example, Muslim servicewomen are permitted to wear hijab as part of their military uniform.

It is also noteworthy the Military Women’s Training Centre in Jordan that has been operating since late 2020 was inaugurated by NATO in June 2021 . The Centre aims to help Jordan attain the 3 percent female representation in its armed forces and will provide NATO-standard basic and military training for 550 military students annually.

In general, Arab armed forces are recruiting more females, who nevertheless continue to face a glass ceiling. The Khawla Bint Al-Azwar Military School in the United Arab Emirates was the first in the Gulf to receive 2014, the first batch of female officers for voluntary 9-month military service .

THE CHALLENGE OF HUMAN SECURITY AND HUMAN DIGNITY

Global security has been challenged by the threat of the coronavirus pandemic since 2020. Covid-19 is a grave reminder that biological threats, whether naturally occurring, accidental, or deliberate, can have significant consequences on the national security of nations.

Covid-19 has disproportionately impacted women compared to men globally. The pandemic’s gendered consequences mimic the effects of war; women were the first to lose their jobs during the pandemic and leadership circles have been constrained to include only male decision-makers.

The move to online meetings, discussions, and workplaces has created new opportunities for some women to participate in political, defense, academic, and professional events. However, women in countries with poor internet connectivity or sanctions preventing them from accessing common tools like Zoom have limited access to such events and their voices have been further silenced. Women residing in Syria and Sudan for example face internet problems that have hindered their work.

In addition, the pandemic has reduced funding for Women, Peace, and Security initiatives. Both regional and donor governments have directed their attention and money toward curbing the impact of Covid-19, which has drained funds that are typically allocated to the advancement of the Women, Peace and Security agenda, gender equality initiatives, and human development. Of course, these funding insufficiencies existed before the pandemic but Covid-19 made them more visible.

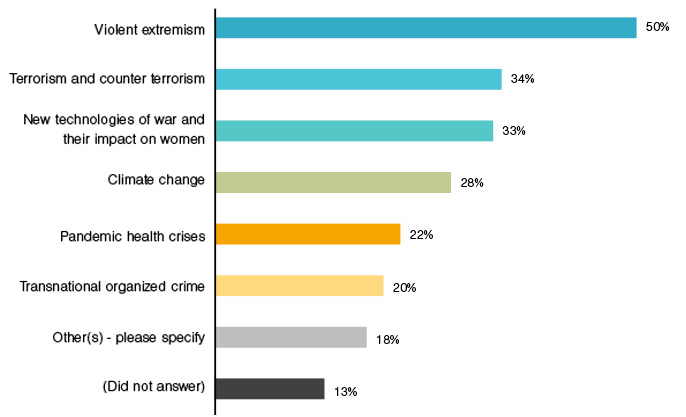

The pandemic has prompted policymakers and academics worldwide to consider human security as an essential element of national security. This has created an opportunity for the Women, Peace, and Security agenda to seek new funding sources from established arms control movements and coordinate with non-governmental organizations like the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, which addresses gender and disarmament. This has also created the opportunity to seize on ongoing discussions of human security during the pandemic to reframe and broaden the Women, Peace and Security narrative and forge partnerships with groups working on demilitarization, disarmament, development, gender equality, and interfaith issues taking into consideration that many local conflicts involve religious issues. As it can be seen in Table 3 below, the women, peace, and security agenda has been negatively affected by emerging global issues with most prevailing the global health crisis, violent extremism, terrorism, and new technologies of war, according to data released by the Global Study on the Implementation of United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325 .

TABLE 3: Emerging Global Issues that have affected WPS agenda.

Source: (https://wps.unwomen.org/data/)

The human dimension of regions or countries under conflict has been impacted by the pandemic. Human dignity is the foundation upon which human rights are based. International human rights law since 1948 recognizes that every human being carries human dignity in that he/she is uniquely valuable and as such he/she is worthy of respect and of having equal basic rights. The Geneva Conventions constituted the basis for international humanitarian law, and the International Criminal Court work relentlessly to protect human dignity and equality envisioning a more just world. Human dignity looking at the human dimension of every conflict and ensuring that the victims’ voices are heard should be at the core of every effort to build a genuinely lasting peace.

Human dignity is causally linked to human security as it is explicitly highlighted in United Nations General Assembly resolution 66/290, according to which “human security is an approach to assist the Member States in identifying and addressing widespread and cross-cutting challenges to the survival, livelihood, and dignity of their people.”

The prime objective of human security is prevention by acknowledging the root causes of risks and by strengthening capacities to build resilience and enhance respect of human rights and human dignity especially for women affected by armed conflict. It is in this context that the creation of a West Asia North Africa Treaty Organization (WANATO), on the pattern of NATO, that is proposed by HRH Prince El Hassan Bin Talal, can serve as a regional institution that will promote not only military and security goals but also enhance human security and cement a process of economic and political cooperation. Just as NATO produced decades of peace and stability in Europe, a regional treaty organization in the WANA region can work in the same direction. Human dignity enabling people to live with respect can lead to the evolvement of peaceful regions.

In times of armed conflicts, human dignity is often not well-protected for women. Thus, compliance with the Humanitarian Law during armed conflicts is not only a legal obligation but a moral duty so that a minimum of human dignity is preserved. The struggle for the promotion of human dignity should go hand in hand with the war on terror and the elimination of weapons of mass destruction.

POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

The natural question that arises is what steps should be taken to advance the Women, Peace, and Security Agenda?

First, the UN and NATO should incentivize the allocation of female military staff to address the gender imbalance in peacekeeping missions, through for example ensuring that the needs of female peacekeepers are met in mission in terms of services, and maternity benefits.

Second, the benefits from a gender balance in peacekeeping missions should be highlighted taking into consideration that women are better suited to work with victims of violence, abuse, and exploitation in conflict and unstable post-conflict zones.

Third, it is important to enhance dialogue with civil society concerning the role of women in conflict and post-conflict situations to attain balanced participation of women in military and defense institutions.

Fourth, institutions and governments should allocate their financial promises and directly support the funding of the Women, Peace, and Security agenda to ensure its efficient implementation. Policies should be transformed into programs and practices to ensure greater gender equality in all aspects of peace and security.

Fifth, dialogue on the security benefits of women’s participation in various capacities, from peace negotiations to governance, should be enhanced. A basis for dialogue is provided by the Global Study on the implementation of UN Security Council resolution 1325 on women, peace, and security which presents clear evidence that women’s participation promotes the implementation and continuity of peace agreements and humanitarian operations.

Sixth, ongoing discussions of human security linked to the pandemic should be seized to reframe and broaden the Women, Peace, and Security narrative and forge alliances with groups working on demilitarization, disarmament, development, and gender equality.

Seventh, women’s participation in Covid action plans must be incorporated for individual countries, including representation on emergency commissions, while public health and education investments in conflict areas should be used to promote gender equality goals and increase the participation of women.

Eighth, governments should reform educational curriculums and textbooks to remove concepts pointing towards traditional and limiting gender roles to empower both men and women equally.

Ninth, non-governmental and international organizations should support women to engage and mobilize constituencies during times of conflict to ensure effective peacebuilding efforts that include resilience and post-conflict rebuilding.

Tenth, leadership programs that seek to elevate women to positions of authority should not simply rely on quotas as benchmarks but focus on recruiting qualified candidates who will promote gender equity, conflict resolution, and responsible governance.

Eleventh, the gains in women’s access and voice made possible by the “Zoom revolution” to support equitable governance and access to the digital policy-making processes should be solidified.

CONCLUSION

The objective of this article was to highlight the roles assigned to women in peace and security with the aim to resolve conflicts, promote reconciliation, and safeguarding national and international security. International organizations like the United Nations and NATO have worked to ensure increased participation of women in peace and security. United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace and Security is unique in that it reaffirms the critical role of women in the prevention and resolution of conflicts, peace negotiations, and peacebuilding. The implementation of UNSCR 1325 in various countries has paved the way for the drafting of Action Plans that foresee equal opportunities for women to join national armed forces. Jordan belongs to that group of countries that has enhanced women’s inclusiveness in the Jordanian armed forces constituting a success story for regional countries to emulate.

The provision of a set of concrete policy recommendations on ways to advance the Women, Peace, and Security agenda aims to underline that inclusion is not only about numbers. It is a matter of expansion of opportunities for women’s increased participation in all aspects of peace and security ranging from counterterrorism and defense planning to peacebuilding processes. 21 years after Security Council resolution 1325, every country and the international community at large should fulfill the expectations and redouble efforts for gender inclusiveness.

LITERATURE

• Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action - The Fourth World Conference on Women, 4-15 September 1995, Accessed at: https://www.un.org/en/events/pastevents/pdfs/Beijing_Declaration_and_Platform_for_Action.pdf.

• Claire Duncanson, Gender and Peacebuilding, Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2016

• Catherine Warrick, Law in the Service of Legitimacy: Gender and Politics in Jordan. Ashgate Publishing Limited: Britain. 2009

• Dalia Ghanem and Dina Arakji, Women in the Arab Armed Forces, Carnegie Middle East Center and Lebanese American University, 2020, Accessed at: https://carnegieendowment.org/files/Women_in_Arab_Armies-final_report_English.pdf

• David Smith and Rosenstein Judith, “Gender and the military profession: Early career influences, attitudes, and intentions.” Armed Forces & Society Journal, 43(2), 260- 279, 2017.

• Georgina Waylen, Karenj Celis, Johanna Kantola and S. laurel Weldon (Editors), The Oxford Handbook of Gender and Politics, Oxford University Press, 2013

• Georg Frenks, Annelou Ypeij and Reinhilde Konig (Editors), Gender and Conflict: Embodiments, Discourses and Symbolic Practices, Farham, UK: Ashgate, 2014

• Implementation of the UNSCR 1325 on Women, Peace and Security in the Arab States, 10 December 2015, Accessed at: http://iknowpolitics.org/en/discuss/e-discussions/implementation-unscr-1325-women-peace-and-security-arab-states

• Joan Johnson-Freese, Women, Peace and Security: An Introduction, Routledge, London, 2018

• Jordan’s National Employment Strategy 2011-2020. Accessed at: http://inform.gov.jo/en-us/By-Date/Report-Details/ArticleId/36/National-Employment-Strategy

• Katherine Maffey and David Smith, “Women’s Participation in the Jordanian Military and Police: An Exploration of Perceptions and Aspirations”, Armed Forces & Society Journal, 46(1), pp 46-67, 2020

• Natalie Florea Hudson, Gender, Human Security and the United Nations: Security Language as a Political Framework for Women, Routledge Publications, 2012

• “National Security Policy-Making and Gender”, Geneva Center for the Democratic Control of the Armed Forces, Practice Note 7, Geneva, 2008

• Laura J. Shepherd, Narrating the Women, Peace and Security Agenda: Logics of Global Governance, Oxford Studies in Gender and International Relations, 2021

• Laura Sjoberg, Gender, and International Security: Feminist Perspectives, Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 2010

• NATO National Report: Jordan Armed Forces 2006, Accessed at: http://www.nato.int/ims/2006/win/pdf/jordan_brief.pdf

• Rana Husseini. Role of Jordanian Women in Peacekeeping Missions Lauded. 23 May 2016. Accessed at: http://www.jordantimes.com/news/local/role-jordanian-women-peacekeeping-missions-lauded

• Sara E. Davies and Jacqui True, The Oxford Handbook of Women, Peace, and Security, (Oxford Handbooks), 2018

• Synthesis Report: A National Dialogue on UNSCR 1325 Women, Peace, and Security in Jordan: A Resolution in Action. UN Women. 2016. Accessed at: http://jordan.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/8/a-national-dialogue-on-unscr-1325-women-peace-and-security-in-jordan-a-resolution-in-action

• Titan M. Alon Matthias Doepke Jane Olmstead-Rumsey Michèle Tertilt, The Impact of Covid-19 on Gender Equality, National Bureau of Economic Research, April 2020. Accessed at: https://www.genderportal.eu/sites/default/files/resource_pool/ w26947.pdf

• Policy Brief: The Impact of COVID-19 on Women, United Nations, 9 April 2020. Accessed at: https://www.un.org/ sexualviolenceinconflict/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/report/policy-brief-the-impact-of-covid-19-on-women/policybrief-the-impact-of-covid-19-on-women-en-1.pdf.

• Women, Peace and Transforming Security, Office of the NATO Secretary General’s Special Representative for Women, Peace and Security, NATO, 31 October 2020

• Women on the Frontlines of Peace and Security, National Defense University Press, Accessed at: https://ndupress.ndu.edu/ Portals/68/Documents/Books/women-on-the-frontlines.pdf

Antonia Dimou

Director of the Middle East and Persian Gulf Department at the Institute for Security and Defense Analyses (ISDA) in Athens, Greece.

Review Paper

- Received: June 25, 2021

- Accepted: July 27, 2021