Dr (Col.) Shaul Shay

Senior Research Fellow, Institute for National and International Security, Tel Aviv, Israel.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.37458/ssj.3.2.6

Research Paper

Received: August 19, 2022

Accepted: November 08, 2022

Abstract: The Russia-Ukraine conflict is witnessing the intensive use of information warfare and psychological warfare which are part of the cognitive warfare. The main goal of cognitive warfare is to wage a war on what an enemy community thinks, loves or believes in, by altering its representation of reality and the art is an important asset and domain of the cognitive warfare. The Venice Biennale serves as a major international art exhibition celebrating achievements in contemporary art, architecture, film, theater, and dance. Some experts call it “the Olympics of the art world.” This article provides analysis of the case study of the Biennale of Venice as a theater of cognitive warfare between Russia and Ukraine. It’s still uncertain how the war will end in Ukraine, but at the 2022 Venice art biennale it is clear which side has prevailed on the art and cultural front.

Keywords: cognitive warfare, information warfare, psychological warfare, art, Venice Biennale.

Introduction

The cognitive warfare and information strategies have been always existed and incorporated into more traditional military warfare to produce effects across traditional warfighting domains and using false information to gain an advantage over one’s opponent is nothing new in the history of strategy but its relative weight in these wars has risen considerably in recent decades, (Kuperwasser, Siman-Tov, 2009).

In World War II, Winston Churchill made his now famous statement: "In wartime, truth is so precious that she should always be attended by a bodyguard of lies", (British National Archives).

NATO currently recognizes five warfighting domains: land, sea, air, space, and cyberspace. An increasing amount of literature suggests adding a sixth: the cognitive domain. The gap this new domain is supposed to fill is the territory fought over in the battle for the hearts and minds of a country’s population,(Bjorgul,2022).

The cognitive warfare is the combination of the newer cyber techniques associated with information warfare and the human components of soft power, along with the manipulation aspects of psychological warfare, (Claverie, Prébot, Buchler Du Cluzel, 2022).

The aim of cognitive warfare is arguably the same as within the other warfighting domains; to impose ones will upon another state .

One way of thinking about it is as a “psychological-social-technical warfare” on the one hand and of a form of “influence warfare” on the other, using cyber means.

Cognitive warfare takes well-known and novel approaches within information, cyber, and psychological warfare to a new level by not only attempting to alter the way people think, but also how they react to information (Bjorgul,2022).

The new momentum for cognitive warfare acknowledges the current digital and social transformations of warfare, which increase both the magnitude of traditional information operations and the range of audiences.

The increasingly widespread and well-planned use of social media, digital and other means of communications has made it possible to reach larger audiences with customized and targeted content at a lightning speed (Pradhan ,2022).

Targets are no longer limited to political and military decision-makers; broader populations are also susceptible to manipulation at a large scale and may be leveraged to influence national decisions. The digital revolution has exacerbated competition in the information domain, by empowering many-to-many communication and drastically increasing the flow of data (Pappalardo,2022).

Definitions of cognitive warfare

To understand cognitive warfare, it is useful to start with the concept of cognition, possibly defined as “the mental process of acquiring and comprehending knowledge, which implies the consumption, interpretation and perception of information” (Ottewell, 2020).

The term cognition refers to the mental process of reasoning, emotions, and sensory experiences that allow us to understand the world, form an internal representation of it, and ultimately act in it. It is therefore a major element of the decision-making process, during which our brain brings into competition different functions (Pappalardo,2022).

Perception is a product of cognition, which is the “mechanism” cognitive warfare attempts to tap into.

Cognitive warfare attempts to alter people’s perceptions, which is the fundamental basis for action.

A cognitive attack aims to change the interpretation of the situation by an individual and in mass consciousness. Cognitive attacks are actively using cognitive biases as automatic shortcuts for the mass consciousness, (Pocheptsov,2018).

There are many definitions of the term cognitive warfare:

- Cognitive warfare - maneuvers in the cognitive domain to establish a predetermined perception among a target audience in order to gain advantage over another party (Ottewell 2020).

- Cognitive warfare - is manipulation of the public discourse by external elements seeking to undermine social unity or damage public trust in the political system (Rosner and Siman-Tov 2018).

- Cognitive warfare - is a strategy that focuses on altering, through information means, how a target population thinks – and through that how it acts. (Oliver Backes and Andrew Swab ,2019).

- Cognitive Warfare - the modes of action available to a state or influence group seeking to manipulate an enemy or its citizenry’s cognition mechanisms in order to weaken, penetrate, influence or even subjugate or destroy it, (Underwood, 2017).

- Cognitive warfare - is the weaponization of public opinion, by an external entity, for the purpose of influencing public and governmental policy and destabilizing public institutions (Bernal, Carter, Singh, Cao & Madreperla 2020)

Together these definitions highlight the core elements of cognitive warfare. They argue that the aim is to influence and/or destabilize through altering how people think and act. It is a war on how the enemy thinks, how its minds work, how it sees the world and develops its conceptual thinking.

The cognitive warfare is more than the sum of various dimensions of information warfare (IW). It integrates all the elements available in the information, cyber and psychological domains and takes them to a new level not only by manipulating the perception of the target population but also by ensuring that the desired reaction is achieved (Pradhan ,2022).

However, they also emphasize that the end goal is to gain some sort of advantage over another party. In sum, the purpose of cognitive warfare is to bring about a change in the target community’s policy, via the cognitive process, advantageous to the attacking state (or non-state actor).

The implementation of cognitive warfare

A cognitive attack is aimed at the transformation of understanding and interpretation of the situation by an individual and in mass consciousness. It is using the emotional stress in order to lower the rational thinking of the object of influence, (Pocheptsov,2018).

The shaping of cognition during a conflict between adversarial actors includes several stages:

- Formulating the narrative of the conflict by describing the reality that prevailed before.

- The need and the legitimacy to change the situation or to maintain it, due to an assessment that the possible end states are inferior to the current situation.

- The reasons for defining the political-military objectives.

- The principles for conducting the campaign such that it will influence the consciousness of the various target audiences in a way that serves the strategic objective.

The various measures and powers exerted need to match the “story” that the actor wishes to convey to the designated target audiences. This is so that the construction of cognition is effective and strengthens the legitimacy of exerting hard power, especially military power, so that the achievements of exerting hard or soft power are translated into political and international achievements; so that is possible to shape an image of victory that illustrates the achievement of the political-military objectives, or offsets the achievements of the adversary (Dekel, Moran-Gilad, L. 2019).

The Russia-Ukraine conflict and cognitive warfare

The Russia-Ukraine conflict is witnessing the intensive use of information warfare and psychological warfare which are part of the cognitive warfare.

During the war between Russia and Ukraine, the same events in the battlefield (the physical domain) were covered by Ukrainian, Russian and International media but they audiences were receiving different interpretations of the same events, leading as a result to different interpretations and conclusions, (Pocheptsov,2018).

Ukraine

President Zelensky, a former TV actor is making appeals for help and assistance to the world on various TV channels projecting Russia in poor light. His acting skill is of great help in projection of the Ukrainian narrative.

Ukrainians were able to show through images and stories that Russia wouldn’t get the quick defeat it had expected, so Ukraine needed help to continue to fight. The videos and images of 13 Ukraine soldiers on Snake Island asking the Russian warship to buzz-off and an old couple daring the Russian soldiers show the determination of Ukrainians to face the Russians and the world treats them as heroes.

Many Ukrainians are functioning as warriors of cognitive warfare which help them in pushing their narrative on social media platforms.

Ukraine’s ability to win the narrative has significant implications for three important constituencies: its own citizens and their fighting spirit, outside nations that can provide financial and diplomatic support, and people within Russia who sympathize with the cause.

US/NATO/Ukraine narrative is carefully planned to project that Ukrainians are giving a tough fight to the Russians and are winning despite disadvantages. Russian loses are shown as its defeat in the conflict and that it is involved in war-crimes and violation of human rights. In this warfare the first movers have the advantage, (Feiner,2022).

Russia

Russia has a more controlled and centralized system that does not help in disseminating information.

The Kremlin described the war as a "special military operation", making it sound quick and relatively painless. The Russian people are the primary audience for its disinformation campaign including a false pretext for the invasion, but narratives outside of state-controlled media betray that account, (Feiner,2022).

Morale is critical in this war. It looks like the Kremlin was hoping that Russia would be able to destroy Ukraine’s morale by making a Russian victory seem like a foregone conclusion, and encouraging Ukrainian fighters to give up, but Russia had underestimated Ukraine’s resilience, including in the information sphere.

Russia’s external disinformation efforts have been largely ineffective because Ukrainian messages are transmitted quickly and target allied populations already skeptical of Russian media.

The Western powers gained advantage over the Russian narrative by releasing intelligence regarding the Russian operations before they occurred. Besides carefully selected videos and images have greater impact.

Jeremy Fleming, the head of Britain’s GCHQ intelligence service wrote in August 2022,

that both Russia and Ukraine have been using their cyber capabilities in the war in Ukraine but

“So far, president Putin has comprehensively lost the information war in Ukraine and in the West, (Arab news, 2022).

The art and the cognitive warfare

The main goal of cognitive warfare is to wage a war on what an enemy community thinks, loves or believes in, by altering its representation of reality and the art is an important asset and domain of the cognitive warfare. Art, sculpture, music and literature were essential for the healthy morale of a nation the community, the family, and the individual.

The war had a major impact on society and on people’s beliefs and attitudes and artists responded to these impacts. Artists searched for an appropriate language to express the chaos and carnage that resulted from modern industrial warfare, reevaluating subject matter, techniques, materials, and styles, as well as their positions and responsibilities as cultural producers (Bourke, 2017).

In the past decades, scholars have traced the effect of war on artists' style, and how these evolutions in artistic modes of expression have influenced the manner in which war is remembered. In doing so, they have examined not just the narratives that art has produced about war, but also the generative influence of war itself (Margaret Hutchison &Emily Robertson,2015).

There is a permanent tension between artistic freedom and censorship. In the same way as art constructs or reconstructs dominant narratives of war, it can also question or unsettle them.

Many artists identified themselves as independent painters, photographers, printmakers, sculptors, advertisers, graffiti artists or cartoonists who only incidentally addressed the topic of war, (Bourke, 2017).

War images are often contested, and this results in various meanings being imposed upon or derived from them regardless of artists' intentions.

The mark of war has been imprinted on everything from stretched canvases to the fuselages of fighter planes (Bourke, 2017).

The recruited art - governments and leaders have recruited artists to create propaganda to generate popular support for wars and to urge the public to make material sacrifices needed to sustain wars.

Some artists were official appointees, sent by their governments to create a record of ‘what was happening’ or to offer visual slogans to aid morale The artists could use the art to bolster recruitment or demonize the enemy, (Bourke, 2017).

In their work, these artists have depicted the opposing side as aggressive, powerful, and savage in order to stimulate animosity and fear for the opposing side. To evoke a sense of nationalism and pride among compatriots, they have depicted battlefield victories, and to stress the need for continued support, they have portrayed the toll of war on soldiers and citizens, (Dawn Brancati,2018).

Art is used to oppose war - Just as governments have commissioned artists to generate support for wars, anti-war organizations have commissioned artists to undermine sympathy for wars and undercut material support for them. Of course, many artists have also independently produced art to agitate for peace.

In their work, these artists have stressed the need to end wars by depicting their brutality, and have tried to generate empathy for their opponents by showing the suffering their opponents experienced at their countries’ hands. They have also used satire to mock the impotency and values of their countries’ leaders. Well-known artists who have produced important works of art against wars include painters Pablo Picasso and Francisco Goya (Dawn Brancati,2018).

The war against art - destruction of art, is used to demoralize opponents during war. Important works of art and architecture have not only been unintentionally destroyed in the course of wars, but they have also been purposely destroyed as a military strategy to dispirit opponents (Dawn Brancati,2018).

The biennale of Venice and the cognitive warfare

The Venice Biennale serves as a major international art exhibition celebrating achievements in contemporary art, architecture, film, theater, and dance. Some experts call it “the Olympics of the art world.”

Since the turn of the twentieth century, countries select artists to represent their nation and respond to a general theme developed by the Biennale curatorial staff.

The war in Ukraine has left its mark on the 59th edition of the world’s most prestigious art event - the biennale of Venice, with Ukrainian artists using it as a showcase of resistance to Russia’s aggression against their people and their culture.

At a time when they are fighting at home, Ukrainian art is taking on special significance in Venice. Ukraine's art is taking center stage at the Venice Biennale, which has made a space at the heart of the Giardini for what is effectively a temporary pavilion for Ukraine.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky opened an exhibition about defending his country's freedom at the Venice Biennale festival. Speaking via video link, he said "art can tell the world things that cannot be shared otherwise". As he talked of his country's fight for freedom, he said: "There are no tyrannies that would not try to limit art. Because they can see the power of art. It is art that conveys feelings," (Katie Razzall,2022).

Pavlo Makov, an Ukranian artist has said: "One of the goals of Russia is to eliminate Ukrainian culture. Culture – the visual arts, literature, music – is how we manage to live together, to answer our questions, to decide complicated questions for society…. it’s a war between two civilizational processes and between two cultures", (Khong, 2022).

Maria Lanko the curator of the Ukraine pavilion at Venice Biennale said:" The cultural barbarism that has accompanied Russia’s countless war crimes is not just collateral damage – the flattening of churches and theatres, the vandalism of school libraries, the burning of museums: these are acts of erasure and eradication. For us being here in Venice to represent Ukraine – it is actually a matter of national security in a way. Which sounds weird, but not weird when a war is going on,” (Khong, 2022).

Art spread rapidly through both traditional and social networks and bolstered Ukraine’s cause in the Western world. The early-stage victory in the information domain has had tangible benefits for Ukraine, which has seen harsh sanctions on Russia imposed by the U.S. and the European Union and grassroots financial support. How long Ukraine can continue to capture the world’s attention is still to be determined.

The "Piazza Ucraina"

The "Piazza Ucraina", is an open-air exhibition which stands at the center of Venice’s Giardini della Biennale. The "Piazza Ucraina", is organized by the curators of the Ukrainian Pavilion (Borys Filonenko, Lizaveta German, and Maria Lanko), along with the Kyiv-based Victor Pinchuk Foundation and an entity known as the Ukraine Emergency Art Fund.

At the piazza looms a tower of sandbags, a replica of the protective measures taken to preserve Ukrainian statues from damage.

Around it, posters are pasted to charred wooden posts, displaying works by Ukrainian artists created since the invasion, either submitted for the event or posted to social media.

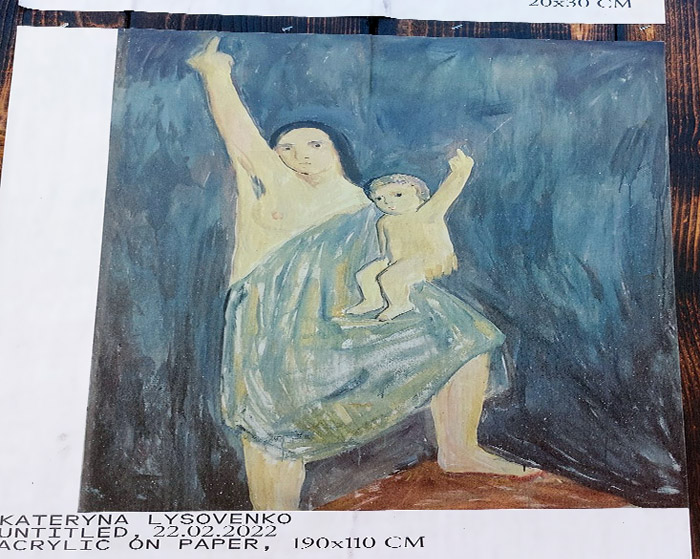

Some are fierce markers of defiance: a mother and child proudly raising their middle fingers, or a crowd pushing back a Russian armored truck. Others reference the many atrocities committed by Russian troops.

Red ballpoint pen sketches by the artist Daniil Nemyrovskyi, show bleak scenes of people hunched close together in bunkers with meagre rations spread on a wooden table.

Each work is stamped with its exact date of creation, as if it were a piece of evidence.

Cecilia Alemani, who organized the Biennale’s main show this year, praised the "Piazza Ucraina" as a potentially defining event at this year’s exhibition.

“In its 127 years of existence, La Biennale has registered the shocks and revolutions of history like a seismographer,” she said in a statement.

“Our hope is that with Piazza Ucraina we can create a platform of solidarity for the people of Ukraine in the earth of the Giardini, among the historical pavilions that were built on the very ideal of nation-state, shaped by twentieth century geopolitical dynamics and colonial expansions.”

Fountain of Exhaustion

The official Ukrainian Pavilion is located in the Arsenale. The Pavilion exhibits the works of Pavlo Makov, whose artistic practices in the early 1990s focused on exploring the parallels between the human body and urban space and have since then largely shifted to elaborating the theme of “the world without us”.

Called the Fountain of Exhaustion, it's a series of funnels arranged in a triangle through which water drips and divides. Makov described it as a metaphor for "the exhaustion of humanity, the exhaustion of democracy", (Katie Razzall,2022).

On the day the Russians invaded Ukraine, co-curator Maria Lanko loaded the funnels into the boot of her car and began the long journey out of Ukraine to Venice.

In Venice, as journalists from across the world queued to interview them, both Makov and Lanko talked of being cultural ambassadors.

Maria Primachenko

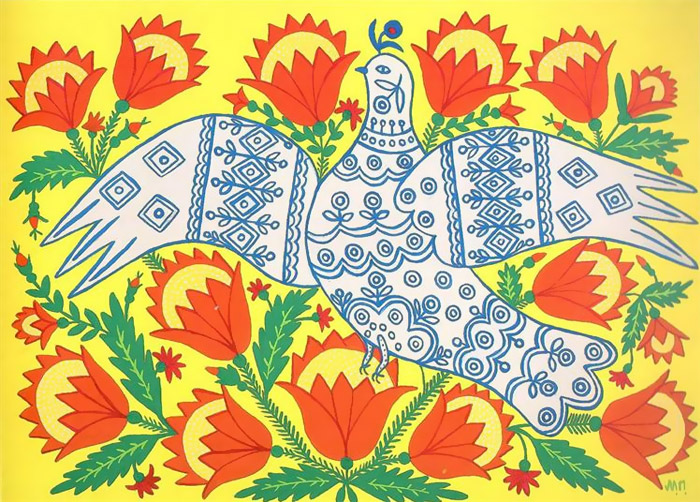

The curator of this year’s main exhibition, Cecilia Alemani, added a gouache titled, Scarecrow, by Maria Prymachenko. Alemani said the addition was “a sign of solidarity [with] Ukrainian culture” (Ruairi Casey,2022).

Twenty-five paintings by Ukrainian self-taught artist were burned during Russia’s invasion. The works had been held by the Ivankiv Historical and Local History Museum, in a town about two hours outside Kyiv that has been shelled by Russian troops.

Maria Primachenko a Ukrainian artist best known for her work in the 1930s who drew on folk traditions. Maria Primachenko has become a symbol of the country's national identity.

Zhanna Kadyrova – "bread"

Kadyrova's exhibition, Palianytsia, which means bread in Ukrainian, features large stones taken from Berezovo, which she has smoothed into loaf-like shapes and sliced. “This stone bread, I changed to real bread for people.”

Since the invasion, this everyday word, which is difficult to pronounce for Russians, has gained a new political valence – a shibboleth separating friends from enemies, (Casey, 2022).

.

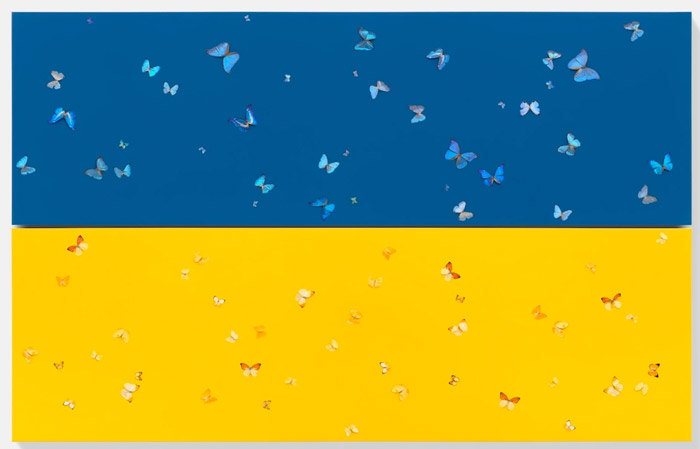

International artists

Another collateral Biennale exhibition, this is Ukraine: Defending Freedom, features work by international artists including Damien Hirst and Marina Abramovic, as well as a blue and yellow sign with a handwritten message from Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, (Ruairi Casey,2022).

The Russian Pavilion

The Russian Pavilion stood locked and empty a sign of the country's isolation. The pavilion, extensively refurbished just in time for last year’s Architecture Biennale, stands completely empty, serving only as a site for protest. The two artists representing the country, Alexandra Sukhareva and Kirill Savchenkov, as well as curator Raimundas Malašauskas, all pulled out of the pavilion shortly after the war began. “This war is politically and emotionally unbearable,” Malašauskas said at the time. (Alex Greenberger, 2022).

Conclusion

War remains unpredictable because it is led by humans, who are emotional and fallible beings. War is not a science but an art, open to evolution and adaptation and complexity in war remains the key word. (Dekel, U., Moran-Gilad, L. 2019).

In cognitive warfare a weaker opponent could achieve strategic victory bypassing the traditional battle-field, if it is fought successfully. This is precisely we are witnessing in Russia-Ukraine conflict (Pradhan ,2022).

It’s still uncertain how the war will end in Ukraine, but at the 2022 Venice art biennale it is clear which side has prevailed on the cultural front.

While an underdog in the ground battle, Ukraine is so far winning the fight for hearts and minds, including in pockets of Russia where protests have broken out, and within many countries that have gone farther than expected in providing support, (Feiner,2022).

The early-stage victory in the information domain has had tangible benefits for Ukraine, which has seen harsh sanctions on Russia imposed by the U.S. and the European Union and grassroots financial support.

How long Ukraine can continue to capture the world’s attention is still to be determined.

Bibliography

- Backes, Oliver & Swab, Andrew. (2019). Cognitive Warfare. The Russian Threat to Election Integrity in the Baltic States. Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs.

- Brancati Dawn, five ways art and war are related, political violence at a glance, January 5, 2018. https://politicalviolenceataglance.org/2018/01/05/five-ways-art-and-war-are-related/

- Bernal, Alonso et al. (2020). Cognitive Warfare: An Attack on Truth and Thought. URL https://www.innovationhub-act.org/sites/default/files/2021-03/Cognitive%20Warfare.pdf

- Bourke Joanna (ed), war and art a visual history of modern conflict, 2017, reaction books. http://www.reaktionbooks.co.uk/pdfs/war-and-art-intro-V2.pdf

- Bjørgul Lea Kristina, Cognitive warfare and the use of force, stratagem, November 3, 2021. https://www.stratagem.no/cognitive-warfare-and-the-use-of-force/

- Ruari Casey, At Venice Biennale, Ukrainian artists defy Russia’s invasion, Al Jazeera, April 22, 2022. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/4/22/venice-biennale-ukrainian-artists-russia-invasion

- Claverie B., B. Prébot, N. Buchler and F. Du Cluzel. Cognitive Warfare: The Future of Cognitive Dominance, First NATO scientific meeting on Cognitive Warfare (France) ‒ 21 June 2021, March 2022. https://www.innovationhub-act.org/sites/default/files/2022-03/Cognitive%20Warfare%20Symposium%20-%20ENSC%20-%20March%202022%20Publication.pdf

- Dekel, U., Moran-Gilad, L. (2019). Cognition: Combining Soft Power and Hard Power. In Y. Kuperwasser, D. Siman-Tov (Eds.), The Cognitive Campaign: Strategic and Intelligence Perspectives, Intelligence in Theory and in Practice. 4, 10, 2019, 151-164. The Institute for the Research of the Methodology of Intelligence and The Institute for National Security Studies: Tel Aviv, Israel.

- Feiner Lauren, Ukraine is winning the information war against Russia, CNBC, March 1, 2022.https://www.cnbc.com/2022/03/01/ukraine-is-winning-the-information-war-against-russia.html

- Greenberger Alex,Venice Biennale Adds Last-Minute Ukraine Solidarity Show Days Before Opening, ARTnews, April 15, 2022. https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/venice-biennale-piazza-ucraina-1234625463/

- Hutchison Margaret &Emily Robertson, Introduction: Art, War, and Truth – Images of Conflict, journal of war and culture stidies,Volume 8, 2015 – issue 2, April 29, 2015. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1179/1752627215Z.00000000065

- Khong Liang, “It’s a Matter of National Security”: the Ukraine Pavilion at the 59th Venice Biennale, Art review, April 20, 2022. https://artreview.com/its-a-matter-of-national-security-the-ukraine-pavilion-at-the-59th-venice-biennale/

- Kuperwasser Y., D. Siman-Tov (Eds.), The Cognitive Campaign: Strategic and Intelligence Perspectives, Intelligence in Theory and in Practice. 4, 10, 2019. The Institute for the Research of the Methodology of Intelligence and The Institute for National Security Studies: Tel Aviv, Israel.

- Ottewell, Paul. (2020). Defining the Cognitive Domain. OTH. Defining the Cognitive Domain – OTH (othjournal.com) https://othjournal.com/2020/12/07/defining-the-cognitive-domain/

- Pappalardo David, "win the war before war?"a French perspective on cognitive warfare, war on the rocks, August 1, 2022. https://warontherocks.com/2022/08/win-the-war-before-the-war-a-french-perspective-on-cognitive-warfare/

- Pocheptsov Georgii, Cognitive attacks in Russian hybrid warfare, Information & Security: An International Journal, vol.41, 2018, 37-43. https://isij.eu/article/cognitive-attacks-russian-hybrid-warfare

- Pradhan S. D, Role of cognitive warfare in Russia-Ukraine conflict: Potential for achieving strategic victory bypassing traditional battlefield, the times of India, May 8, 2022. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/blogs/ChanakyaCode/role-of-cognitive-warfare-in-russia-ukraine-conflict-potential-for-achieving-strategic-victory-bypassing-traditional-battlefield/

- Razzall Katie,Venice Biennale: Ukrainian art exhibition opens in shadow of war, BBC news, April 22, 2022. https://www.bbc.com/news/entertainment-arts-61186014

- Remarks before the Nazi War Criminals Interagency, Inter-Agency Working Group, National Archives. https://www.archives.gov/iwg/research-papers/weitzman-remarks-june-1999.html

- Rosner, Yotam & Siman-Tov, David. (2018). Russian Intervention in the US Presidential Elections: The New Threat of Cognitive Subversion. INSS Insight, No. 1031.URL: Russian Intervention in the US Presidential Elections: The New Threat of Cognitive Subversion | INSS

- Ruairi Casey, At Venice Biennale, Ukrainian artists defy Russia’s invasion, Al Jazeera, April 20 ,2022. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/4/22/venice-biennale-ukrainian-artists-russia-invasion

- UK spy chief says Putin is losing information war in Ukraine — The Economist, Arab news, August 19, 2022. https://www.arabnews.com/node/2145941/world