Prof.dr Miroslav Mitrovic, Union University "Nikola Tesla", Faculty of Law, Security and Management

Senior Research Associate Milovan Subotić, PhD, Strategic Research Institute, Belgrade

Research Paper

Received: August 9

Accepted: November 3

Abstract: The Kosovo conflict is a frozen intergroup ethnonational conflict, historically long-lasting, complex, and burdened with accumulated conflicting interests and stereotypes. By relying on several analytical instruments, work in the paper focuses on determining the typology of conflict and its characteristics. Based on Hofstede's scale of cultural factors, the components of the strategic culture of Albanians and Serbs have been determined, which determines their attitude toward resolving the conflict. The essential preconditions for establishing the environment necessary to create a sustainable solution to the conflict are presented. The Circle model was the basis for a hypothetical answer to the Kosovo conflict that would lead to a stable and mutually acceptable solution. With all the limitations and generalizations of this complex conflict, the paper provides a general framework for the possible "intersection" of the Kosovo conflict, a kind of Gordian knot in the Balkans.

Keywords: conflict resolution, intergroup conflict, ethnonational conflict, Kosovo, Albanians, Serbs.

Introduction

Conflict can be defined as a sharp disagreement or opposition in terms of interests or ideas and includes a marked divergence of interests with the belief that the parties' current aspirations to the conflict cannot be realized simultaneously. There are different forms of conflict (personal, interpersonal, and intragroup), and for analysis within this paper, we observe intergroup conflict. Intergroup conflict is between organizations, ethnic groups, warring nations, or homogeneous entities within fragmented communities. The characteristics of such conflicts are their complexity, multi-layered causes, and the probable presence of a third party involved. Therefore, resolving such conflicts is the most complex. Intergroup conflicts have tremendous destructive potential. In his work, Lewicki (Lewicki et al. 2016: 20) Sublimating the conclusions of previous research (Deutsch 1958; Folger et al. 1993), Lewicki expressed the complexity and destructiveness of intergroup conflicts, which are expressed through:

Competitiveness – the parties have ultimate requirements that represent a zero-tolerance relationship. The parties believe that both of them cannot achieve their goals. The goals are highly opposed.

Misperception and bias; The intensity of the conflict leads to a distortion of perception and subjective positioning. Therefore, there is a tendency to characterize the whole conflict environment (participants and non-participants) as if they were with or against them. In addition, thinking is burdened with stereotypes and bias, and the parties support people and events that represent their position and reject entirely those who oppose them.

Emotion strongly marks intergroup conflicts; The emotional charge leads to the parties' anxiety, irritation, anger, and frustration. Emotions overwhelm clear and rational thinking, and the parties can become more and more irrational as the conflict escalates.

Reduced communication; Productive communication declines with conflict. The parties communicate less with those who disagree with them and more with those who agree. The communication that takes place is often an attempt to defeat, humiliate or expose the position of another or to strengthen one's previous arguments.

Blurred problems: Considering all the above, we come to a situation where the central issues in the dispute become blurred and poorly defined with the escalation of generalization. The parties are becoming less and less clear about how the dispute started, what it is "really about," or what will be needed to resolve it. The conflict becomes a whirlwind that draws in unrelated questions and innocent observers.

Firm commitments; The parties are closing in on their positions, responding to challenges from the other side, and thinking processes become rigid. Parties tend to see questions as simple, "or/or" rather than complex and multidimensional. They become more and more committed to their points of view and less willing to give up on them for fear of looking defeated and humiliated.

Increased differences, minimizing similarities; By closing in on their positions, the parties experience more and more blurred and superficial obligations and issues but already tend to see each other as complete opposites. This distortion leads the parties to believe that they are further away from each other than they are, which reduces the capacity to find a common language. The factors that distinguish and separate them become emphasized, while the similarities become too simplified and minimized.

Conflict escalation. As the conflict progresses, each side becomes more rigid in its views, less tolerant and communicative, and more emotional. The result is an attempt by both sides to win by increasing their commitment to their position and increasing the resources and perseverance invested in winning. Both sides believe adding more pressure (resources, commitment, enthusiasm, energy) can force the other to capitulate and admit defeat. The escalation of conflict levels and commitment to victory may increase so high that the parties will destroy their ability to resolve the conflict or will never be able to have a relationship with each other again.

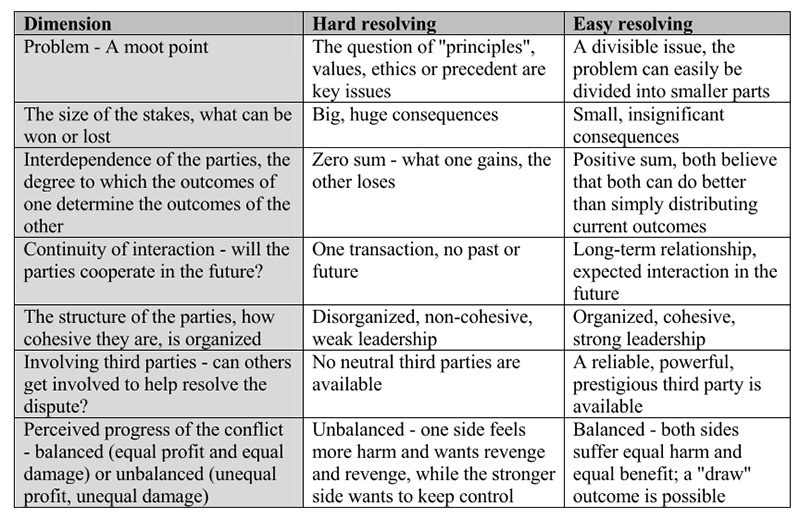

Intergroup conflicts are not balanced and equal in terms of resolution difficulty. Several factors influence whether an integrative conflict is more manageable or more challenging to resolve. A framework for analyzing the severity of intrinsic conflict can be found in Greenhalgh's (Greenhalgh 1986:45-51) work, which identified the characteristics of easily and difficultly resolved conflicts based on conflict issues, interdependence, and projection of relations, the cohesion of parties to the conflict, existence of an objective third party and balanced development of conflict resolution.

Table 1: Assessment of the degree of difficulty in resolving intergroup conflicts

Genesis and Classification of the Kosovo Conflict

The history of relations between Serbs and Albanians has an extended historical connotation. Namely, both nations have shared the same space for almost a whole millennium, and their relations have followed historical trends that have affected the space of Kosovo and Metohija. Furthermore, the Balkans are from the Middle Ages until now (Woehrel 1999).

Centuries of coexistence in the same area are marked by relations of centuries of conflict, metaphorically described as a "pendulum of domination" (Nikolić 2003:55).

- Early history of relations and the beginning of the conflict (Middle Ages-mid-19th century); Before the Ottoman occupation of the Balkans, Serbs and Albanians lived on good terms based on their affiliation with the Christian Orthodox Church (Zdravković 2021: 183-204). The following contributed the most to the further development of relations, which grew into a state of continuous conflict in the pursuit of domination: 1) Islamization, 2) taking over the role of Grand Vizier by the Albanians and 3) great migration of Serbs. A severe conflict arose during the liberation wars of 1876-1888, when Albanians, in fear of losing their privileges, intensively inhabited certain areas, permanently changing the ethnic structure of the population. From then until today, the roles of the subordinate and superior people in Kosovo and Metohija have changed alternately (Nikolić 2003:55-63).

- The middle of the nineteenth century until the Balkan wars. The late Ottoman rule over Kosovo was marked by the domination of Albanians and discrimination against Serbs with their emigration from these areas and the establishment of the ‘Prizren League’ as the embodiment of the idea of a single Albanian nation.

- The period of the Balkan wars (1912-1914). An attempt to establish Serbian domination over the Albanians in Kosovo and Metohija, the formation of the Albanian state, and the opposing attitude toward the disappearance of the Ottoman Empire.

- World War I (1914-1918). Albanian domination and discrimination against Serbs, with strong revanchism and cruel acts against the Serb population and Army in the retreat through Albania in 1915, took about 150,000 Serb lives.

- First Yugoslavia (1918-1941). The dominance of Serbs over Albanians. Serbia was a victorious power in the First World War, Albanians were not recognized as a constituent people of the new state, and the privileges they enjoyed in the Ottoman Empire were revoked , leading to dissatisfaction and ethnic distancing with frequent Albanian armed uprisings.

- World War II (1941-1945). The Albanian National Liberation Movement, which aims to unite Kosovo with Albania, joins the communist revolutionary movement of Josip Broz, promising that after liberation and a revolution, Kosovo will receive the status of a republic. At the same time, most Albanians support the Italian fascist occupation, which allows them a dominant position and constant repression of Serbs.

- The period after the Second World War (1945-1966). The domination of the Serbian communist elite over the Albanians and some of the expelled Serbs who were not allowed to return. Kosovo still needs to receive the promised status of a republic, which caused dissatisfaction and disappointment among Albanians. The stern measures of the communist leadership additionally influence the creation of the cohesion of the Albanian national identity in Kosovo.

- Period of pronounced autonomy (1966-1989). The period of Albanian domination over Serbs. Although the idea of obtaining the status of a republic was rejected by the communist leadership of the SFRY, the Albanians, by dominating the institutions and strengthening their national identity, worked persistently to make Kosovo independent (Trbovich 2008: 233-234). With the 1974 Constitution, Kosovo gained a dominant role over the Republic of Serbia. There is a sudden Albanian cultural awakening and intensive cooperation with related circles in Albania. Kosovo's significant modernization and industrialization also mark this period to help other parts of the SFRY. However, Albanian society remains much closed, based on tribal relations, which, whenever possible, are placed before the state's law. During this period, organized extremist movements of Albanians (Kosovo Front for National Liberation, Kosovo Marxist-Leninist Organization, Communist-Marxist-Leninist Party of Albanians in Yugoslavia, and the Red National Front) appeared, which represent the core of the later formed terrorist organization, the so-called ‘Kosovo Liberation Army’ - KLA. It is estimated that at least 100.000 Serbs and Montenegrins left Kosovo during this period due to pressure and attacks on property and personal security. The communist government did not respond effectively, and part of the problem was covered up (Blagojevic 2000: 224-230).

- The period of disintegration of the SFRY and armed conflicts in Kosovo (1989-1999). This period is recognized as "a period of Serbian domination, complete paralysis, and discrimination against Albanians" (Nikolić 2003:61). This attitude is a reaction of Serbian institutions to decades of Albanian pressure. In response, Albanians 1990 published their Constitution and proclaimed the 'The Republic of Kosovo,' building parallel institutions. By repealing the provisions of the 1974 Constitution, Serbia is taking control of its province. Massive personnel changes have been made in the Kosovo administration, leaving some 85.000 Albanians out of work. At this moment, Serbs and Albanians are ultimately confronted and separated. Even in reaching certain compromises and agreements with the Serbian state, their compatriots denounce Albanian political representatives as traitors to the national interest (Lulzim 2018). A particular frustration of Albanians arose when they realized that the so-called ’Kosovo issue’ did not fall within the framework of the 1995 Dayton Agreement. Then comes the escalation of the conflict initiated by the KLA. Their attacks aimed not only at Serbs and other non-Albanians but also, according to their criteria, ‘Albanians loyal to Serbia’ (Nikolić 2003:62). At the end of 1998, the FRY, which was attacked, responded with extensive anti-terrorist action. Combat operations and internal KLA pressure on civilians set off a wave of refugees, which served as an excuse for NATO intervention in March 1999. The fighting lasted 78 days and ended with the ‘Kumanovo Agreement,' the main provisions of which envisaged the withdrawal of the Yugoslav Army from the territory of Kosovo and the establishment of an international protectorate. Later, the status of Kosovo was determined by UN Resolution 1244. The Yugoslav Army (YA) withdrawal triggered the exile of Kosovo Serbs and the establishment of a state of domination and repression of Albanians (Nikolić 2003:63).

- The period after the NATO intervention (1999-present). The period of Albanian domination, isolation, persecution, stigmatization, and terror against Serbs in Kosovo and Metohija can be observed through the following periods: 1) until 2004 and the ‘March pogrom of Serbs’ (Sotirovic 2014) , 2) until 2008 and the self-proclaimed independence of the ‘Republic of Kosovo.' , 3) until 2013 and the ’Brussels Agreement’ (GRS, 2013) , and 4) the current period of frozen conflict, negotiations on technical issues, latent conflict, complete separation of Serbs and Albanians, and lack of communication, cooperation, dialogue, and efforts to improve the situation (RSE, 2021).

Ethnonational Characteristics of the Kosovo Conflict

Observing the structure of the Balkans, it can be concluded that it represents a diverse multiethnic entity (Raduški 1997). Throughout history, the imposition of a robust administration that has stifled the ethnic rights of individual peoples in the context of changes in the borders of states that emerged and are extinguished in the Balkans has, as a rule, always led to more or less violent ethnic conflicts (Subotić and Mitrović 2018: 22-33). Ethnic and cultural diversity does not lead to conflicts between ethnic groups. Social conflicts are an essential feature of human society, and only under certain circumstances do they take the form of ethnic conflicts. There are different types of ethnic groups and different types of ethnic conflicts. As for the beginning of the ethnic conflict, it is more appropriate to talk about the period of longer or shorter incubation than the beginning of the ethnic conflict. Also, it is believed that there is no single cause that initiates ethnic conflict, but predisposing and initial factors that initiate and accelerate ethnic conflict (predisposing and triggering factors). Ethnic identities are constructed from objective attributes and contain subjective feelings and beliefs that reinforce such attributes and sometimes create them. How states and governments treat ethnic diversity within their borders also creates ethnic conflict. Government ethnic policy often generates conflicts but can be conducted to weaken, resolve, or avoid them. The formulation and modification of specific ethnic policies play an essential role in the conflict. Governments are rarely neutral observers, and more often, they participate in the dynamics and evolution of ethnic conflict. Ethnic conflicts always have an international component (Stavenhagen 1996).

Ethnic conflict is a prolonged social and political confrontation of opponents who define themselves and others according to ethnic characteristics. That means that criteria such as national origin, religion, race, language, and other features of cultural identity were used to distinguish between opposing groups (Stavenhagen 1996).

Observing the conflict in Kosovo and Metohija, it can be seen that it represents an ethnonational conflict between Albanians and Serbs. Namely, the conflict motivation and potential are in the ethnonational characteristics of both nations. At the same time, escalation factors cannot be ruled out in certain phases of this long-lasting conflict, such as religion and identity (Subotić 2017; Subotić 2019).

To achieve the maximum possible, sustainable, and mutually acceptable way of resolving the conflict, it is necessary to identify the basic ones, its cultural framework, and critical interests disputed by the parties, as well as preconditions that should provide conditions for resolving the conflict.

Communication and cultural framework of the Kosovo Conflict

The complexity of ethnonational conflicts requires a comprehensive approach to resolving them. Ethnic conflicts relate to conflicting interests, constitutional arrangements, political power, and incompatible (cultural) identities. From the point of view of the analysis of the characteristics of the ethnonational conflict in Kosovo, we start from the position that culture and identity are the basic concepts for studying ethnic conflicts (Ross 2007). In his discussion of the cultural-identity root of ethnonational conflicts, Ross (2007) states that: 1) cultural identity disputes offer a better understanding of multiple strata and problems in long-standing unresolved ethnic conflicts, 2) disputed cultural expressions can focus on emotional dimensions of conflicts and can complement models and tools of negotiation, 3) since cultural conflicts are constructed, they can also be reshaped and reconstructed in that direction to allow de-escalation. Of course, ethnic conflict concerns issues of culture and identity, tangible interests and power, state order, and legislation. Psychological and cultural examinations of ethnic conflict can help us to understand how the parties understand the development of events and critical issues and how they express their fears and frustrations. Through them, it is possible to penetrate how the parties position themselves in the conflict, its intensity, and the reasons for the conflict itself. Psychocultural narratives are invoked in psycho-cultural dramas that polarize events about cultural claims, threats, and rights that cannot be negotiated and become necessary because of their connection to group narratives and essential metaphors crucial to group identity. That is why it is crucial to understand the intensity of identity conflicts because it reveals the existential fears caused by group narratives (Ross 2007). They are shaped into complex forms of conflicting communication. Communication between rival, nationalist-oriented ethnic groups is generally divergent, as their semantic frameworks provoke each group to resist communicative contact with the other. The intransigence of nationalist views of the world and life hinders their ability to establish the overlap of meanings or reference points necessary to initiate actual dialogue. Their internal logic shows resistance to the essential condition that enables understanding between the subjects who communicate (Anastasiou 2008:153). It is challenging to achieve the essential precondition for resolving the conflict - establishing communication. Namely, communication is a central element in all conflicts, poor communication often creates or exacerbates conflict, and conflict inhibits and distorts communication. Therefore, improving communication before and during the conflict is essential for conflict prevention and effective management or resolution (Burgess and Burgess 1997:65).

Namely, the complexity of the problem of culminated ethnonational relations that led to the conflict points to the need to approach it gradually and flexibly, respecting the possibility of a linear (through institutions responsible for specific problem areas) but also Foucault's approach (Rabinow and Rose 2003). By cumulative action of solved sub-problems, i.e., conflicts at the micro-level, a shift in a linear and rational solution of segments that make up a general problem can be achieved. That implies the dispersion of power in resolving the conflict; the possibility of affirming the ability of an individual to contribute to solving problems on a personal level is delegated.

National culture, or culture defined at the level of a particular ethnic community, influences the interests and priorities of negotiators, as well as their preferred strategy or style of conflict resolution. The most widely studied cultural difference that influences one's negotiating strategy is the dimension of individualism versus collectivism. In individualistic cultures, the needs and autonomy of the individual are more important than those of the larger group. In contrast, the group's needs tend to take precedence in more collectivist cultures. This difference in cultural norms can lead to different conflict resolution styles because of what they imply about negotiators' goals and feelings of confrontation. It is, therefore, essential to explore how cultural norms, such as collectivism, influence conflict resolution strategies and through which mechanisms (Gomez and Taylor 2018).

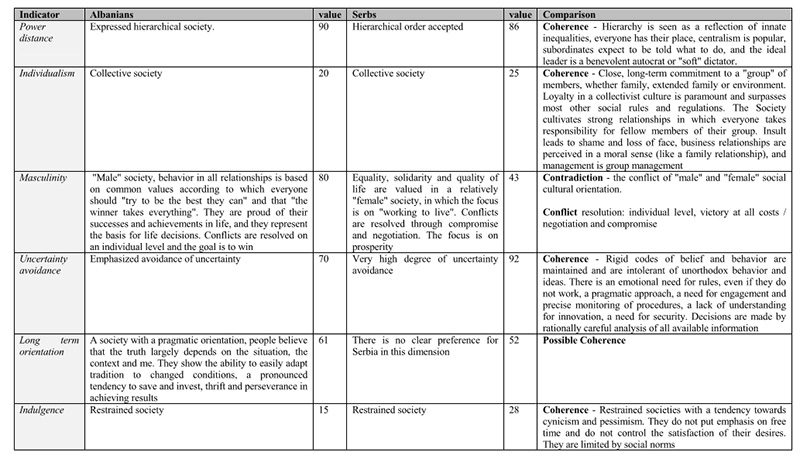

In analyzing cultural orientation according to possible forms and styles of conflict resolution, we will use the Hofstad scale of cultural characteristics of two peoples (Table 2): Albanians and Serbs (Hofstede Insights 2022).

Table 2: Comparative overview of the values of Albanians and Serbs in the context of the commitment to conflict resolution (Authors)

General description of cultural characteristics based on the Hofstede scale:

Albanian society is firmly committed to authoritarian leadership; with a strong sense of collectivity; commitment to achieving results and personal conflict resolution with the imperative of success; the existence of rules and norms (at least formal ones); preference for pragmatic solutions; future-oriented; with considerable restraint and control of daily desires.

Serbian society is committed to authoritarian leadership, with an emphasis on collectivity and; a relative focus on well-being; conflicts are resolved through compromise and negotiation; rigid codes of belief and behavior are maintained, and intolerance towards unorthodox behavior and ideas is expressed; without pronounced long-term orientation; and a pronounced restraint in meeting individual needs.

The Kosovo conflict is a complex confrontation between the Albanian and Serb peoples. Considering the above, the Kosovo conflict is inherently complex, compound, and burdened with all cultural and ethnic-based conflict characteristics. Also, the current general understanding of this conflict indicates that it is difficult to resolve with tremendous destructive potential. To enable modeling of the solution to this conflict, it has to perform a complex analysis of its genesis and typology.

Analysis of the ‘Drivers’ of the Kosovo Conflict

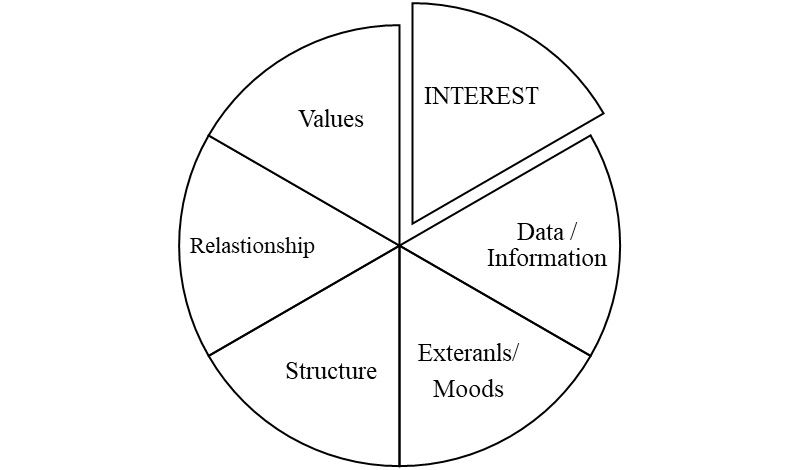

It stated earlier that ethnonational conflicts are based on a cultural-identity schism. However, its escalating forms, such as the centuries-long low-intensity conflict in Kosovo, always have physical, material, structural, institutional, political, economic, and other causes in their content. For this paper, we will use ’The Circle of Conflict model.

As a model or map of conflict, the Circle of Conflict tries to categorize the root causes or ‘drivers’ of conflict situations the researcher faces. Based on it, it is possible to create a framework for diagnosing and understanding the factors that create or encourage conflict. In addition, the Circle model offers basic strategic directions on encouraging conflict toward a solution (Furlong 2005: 29-35).

Figure 1. Overview of the content of the "Circle of Conflict" model (Furlong 2005: 21)

Interest – represents the declared interest of the parties to the conflict. Apart from the expressed interests, hidden interests may depend on the structure and nature of the conflict subjects, i.e., "leaders" in the conflict and their leaders and elites (political organizations, ethnic, religious, national groups, economic organizations, and states).

Values - includes all values and beliefs of the parties that contribute to or provoke the conflict. That includes ultimate values or values that define life (such as religious beliefs, ethics, and morals) and more straightforward everyday values used in a business or work context (such as customer service values and community loyalty). Conflicts of value occur when different values of the parties skirmish, and their clash causes or worsens the situation. Because values, morals, and ethics are so important to human beings, conflicts of values have the potential to heal the situation and involve personality traits.

Relationship – identification of specific negative experiences in the past (previous experiences, history, bad relationships) as a cause of conflict. Relationship conflict arises when previous history or experience with the other party creates or creates a current negative situation. Relationship problems often lead to stereotyping, lead people to limit or cut off communication with the other party, and often lead to unjust behavior, where one party notices unfair treatment and retaliates against the other party; the other side then perceives this as an unprovoked attack and in a way retaliates against the first party, which leads to further retaliation and endless conflict.

Externals/Moods - encompasses external factors that are not directly part of the situation but continue contributing to the conflict. External drivers create an atmosphere of conflict, which occurs when external forces cause part or all of the problem, thus exacerbating an already difficult situation.

Data - or information is identified as a critical driver of conflict. Data conflicts occur when the information that parties are working with needs to be more accurate or complete, or there is a difference in information - one party has essential information, and the other does not. These data problems often lead to further negative assumptions and further data problems. Another critical data issue is the interpretation of data in which the parties interpret the same information differently.

Structure - covers several different types of situations, all focused on problems with the very nature or structure of the system in which an individual or community realizes itself. Three common structural problems are limited resources, problems with authority, and organizational structures.

Analysis of conflict characteristics and preconditions for its resolution

The Kosovo conflict has dominant complex and destructive features of intergroup conflict. Using the indicators proposed by Lewicki (Lewicki et al. 2016:20), we can say that the Kosovo conflict is characterized by the following:

- Competitiveness; exceptionally opposing goals: Albanians - nothing less than complete independence; Serbs - nothing more than autonomy.

- Misperception and bias; the longevity and intensity of the conflict lead to a distortion of the perception and mutual subjective positioning of Albanians and Serbs. There are solid stereotypes, harsh classifications, and divisions between 'us and them.' Stereotypes are nourished and further developed. The critical approach to analyzing problems from the composition of both nations is minimal and marked as a ‘betrayal of national interests.'

- Emotion; A vital feature of the Kosovo conflict. There is a connection between the roots of the identity of Albanians (‘Albanians are Illyrians, and Kosovo is an Illyrian homeland before the arrival of Slavs – Serbs’) and Serbs (‘Kosovo is the cradle of Serbian statehood and national identity’) with the essence of conflict resolution. This narrative, used in daily political spheres, contributes to the constant growth of emotional charge with expressed frustrations and restrained rational thinking about a possible solution to the conflict but already contributes to maintaining its frozen, permanent state.

- Reduced communication. Ethnic communities in Kosovo itself live in almost wholly divided environments, and communication is limited to legal forms. Communication within the negotiations is also minimal and sporadic, with no sincere progress or contribution to the solution. Narrative and gestures in sporadic negotiations are provocative, with a tendency to defeat and belittle the other side. The Albanian side believes that only full recognition of independence is possible. The Serbs believe the status should be discussed later, with the absolute rejection of Kosovo's self-proclaimed independence.

- Blurred problems; The general environment of forced stereotypes, the absence of a rational approach to the problem. A tense general (through the media) and particular narrative (in occasional negotiation sessions of negotiating groups of different levels) contribute to the loss of the image of the essence of the problem.

- Firm positions; The Albanian and Serbian sides are firmly positioned in their positions, strongly argue for the interpretation of the problem from their point of view, and blame the other side for all the failures and problems. Possible compromises that relativize the set goals (independence vs. autonomy) are considered betrayal and defeat on both sides.

- Increased differences, minimizing similarities; By consolidating their positions, Albanians and Serbs constantly emphasize differences (ethnic identity, language, religion) and confront common characteristics (history, shared living space, economic interests). As a result, communities are becoming increasingly distant, and finding coexistence becomes more and more difficult.

- Conflict escalation. The conflict is currently in a frozen phase. However, all the antagonisms between the two sides point to the danger of possible escalation. Albanians and Serbs are completely divided on the issue of solutions, communities are communicatively and functionally separated, and strong stereotypes and dehumanized perceptions of the other side dominate, which is a fertile ground for escalating conflict.

Observing the dimensions of the conflict, based on the Greenhalgh matrix (Greenhalgh 1986: 45-51), the Kosovo problem has a monolithic dimension of the dispute over one indivisible problem: the issue of statehood. A possible solution is to simplify this issue and deviate from absolute recognition by insisting on general warming of relations, relaxation of general communication between Albanians and Serbs, and solving individual economic and life issues (social protection, education, health, culture, science). Reducing the conflict potential of relationships through establishing functional and balanced relations, with the obligatory absence of domination, with developed interethnic communication would separate the public from the stereotypical approach to another community, and the problem would be more relaxed. Such a division of the problem into smaller parts would contribute to its simplification, and only the solution of the ultimate issue of the dispute, ' independence vs. autonomy,' would gain the perception of reduced emotional and rational understanding. This top issue would be considered a complex and not a monolithic problem, with finding an emotional, identity, social, legal, economic, and security framework for its solution. That would stimulate cultural characteristics that determine the satisfaction of needs and the absence of uncertainty.

Furthermore, with such an approach, Albanians and Serbs would feel an insurmountable gap and an issue that only allows for mutual satisfaction. Deviating from the ‘zero-sum’ approach, in which only the defeat of the opposite side is accepted as a possible solution, must change. Change must come from political elites and cultural and social circles, which are conditioned by the collectivity and cohesion of both sides. At the same time, the media have a significant role in this process by suppressing negative narratives, generalization, encouraging and developing new stereotypes, but by highlighting positive and motivating examples with emphasized objectivity in reporting. In this approach, it is possible to use the cultural characteristics of the Hofstad, i.e., the commitment of both peoples to the acceptance of self-sufficiency and emphasized collectivity.

The current development and conflict with the manifested aspiration for domination, the lack of communication between groups, and the emphasis on only the ultimate solutions indicate that both nations have been tragically misled. Namely, the relationship between Albanians and Serbs in Kosovo is seen as a dead-end; that is, the future of relations is not projected. That is a profoundly wrong approach because both nations share the same space and are inevitably directed toward each other in the future. It is necessary to build awareness of possible coexistence by presenting the shared future of both peoples in the same living space, which is rapidly shrinking in the era of globalization, and borders are becoming virtual domains that do not hinder people from exchanging ideas, knowledge, cultural and products and services.

The third parties involved had a significant impact on the Kosovo conflict. The United States and Germany are predominantly on the side of Albanian interests, which conditions the support of institutions in which these countries are leaders (NATO and the EU). The performance of the United States and Germany so far can be interpreted as biased, with unconditional support for Albanian interests, both in international forums, bilateral action, and presence on the ground in Kosovo (military, police, and other forces), with pressure and conditioning from the Serbian side. On the other hand, Serbian interests at the level of international politics (they do not have an effective presence on the ground in Kosovo) are represented by Russia and China. However, both forces state that any solution Serbia adopts is acceptable to them. Also, both forces do not exert extraordinary pressure on Kosovo and do not show a desire for more significant engagement in resolving the conflict. No objective and neutral third party in the Kosovo conflict contributes to its continuation and current frozen form. Third parties (USA, Germany, Russia, and China) are engaged in the conflict, primarily guided by their interests and projections of the realization of power. That did not contribute to establishing trust and a sustainable and acceptable solution but to a state of coercion and imposed compromises that can be equated with the continuation of the ‘pendulum of domination.'

Preconditions for Resolving the Kosovo Conflict

The conflict in Kosovo and Metohija is predominantly characterized by: longevity, the complexity of value and historical contradictions, the sociological and physical distance of participating parties, the existence of stereotypes and prejudices, diametrical opposition of goals, interests of external participants, cultural and religious opposition, identity conflict and lack of communication (Mitrović 2022).

An earlier analysis suggests that the existence and assumption of expectations of a continued 'pendulum of domination' deepen the crisis and disrupt relations. At the same time, there is a real need to establish a sustainable solution to the conflict based on respect for interests and a sincere commitment to the peaceful coexistence of two ethnic communities, that is, existence through coexistence. Implementing solutions based only on the bureaucratic application of the law is rigid and raw. It has shown inefficiency without communication and bringing the solution closer to all community levels. Moreover, this approach leads to a new escalation of the conflict due to the inability of the state to establish effective multiethnic cohesion, and its actions contribute to inciting ethnonational intergroup conflict. The need to establish direct interethnic communication at the micro-level of communities was emphasized, which will gradually reduce the influence of stereotypes. The environment of long-term oriented communication that would lead to conflict resolution needs to have the following prerequisites:

- Establishing restorative justice. The crimes are resolved, with compensation, identifying and apprehending those responsible, and involving the community in resolving conflicts. The parties' participation is an essential part of the process that emphasizes building relationships, reconciliation, and developing agreements on the desired outcome between victims and perpetrators. Restorative justice processes can be adapted to different cultural contexts and the needs of different communities (OUN 2006). In the case of the conflict in Kosovo, the parties to the conflict must take an objective and impartial position that will: punish all perpetrators and their superiors, send a message that crimes committed during the conflict do not become obsolete, and enable victims' families. In this way, it is possible to understand restorative justice in the context of large-scale conflict and its role in peacebuilding (Rohne et al. 2012:16-19).

- Suppression of the truth dichotomy: Different interpretations of truth and its emphasis as an axiom in creating relationships contribute to the absence of constructive communication. That is the case for the Western world and the Albanians, the NATO air operation' humanitarian intervention’, and for the Serbs aggression and war; Albanian refugees were ‘victims of genocide,' and Serb civilian victims were ‘collateral damage’; the secessionist movement and the terrorist organization of the KLA are ’freedom fighters,' and the legal formations of the YA are occupiers on their territory. Different attitudes toward the truth are based on opposing political goals and stereotypes. The political abuse of centuries-old myths about Kosovo has resulted in cycles of conflict at the macro and micro levels (Nikolic-Ristanovic 2012:160). Suppressing different interpretations of the truth also reduces emotional distance and a more rational perception of achievable goals. However, in addition to the parties directly involved in the conflict, a third party, the international community, has a significant role in establishing a balanced relationship with the truth. Its role is particularly damaging in applying the policy of double standards when the international community seems to take a side in the conflict instead of mediating and helping to build trust and a multicultural society. Insisting on the ‘truth’ that is accepted by only one of the parties to the conflict is especially risky when it comes from a party that acts as a mediator in resolving the conflict or when a third party is inconsistent, i.e., sends contradictory messages and thus loses trust (Nikolic-Ristanovic 2012:164).

- Establishing an immediate dialogue. Direct dialogue gives people the opportunity to learn more about themselves and others. Negative stereotypes can be reconstructed, and a more complex understanding of oneself can replace monolithic self-representation. By discovering the opposite aspects of oneself and the similarities between oneself and the other, one can achieve the process of communication and deconstruction of a negative view of the other side (Bar-On 2005:184). Research suggests that direct interaction between people with different beliefs or cultural, ethnic, or religious statuses will increase the ability to understand the perspective of opponents' attitudes and thus reduce prejudice against that group (Allport 1954; Duckitt 1992).

The proposed solution to the Kosovo conflict

Based on the characteristics of the conflict presented so far and the potential for its resolution/escalation, we will start modeling the resolution of the Kosovo conflict based on the Circle Model. We will consider the interests, values, and relationships of the conflicting parties, the data/information aspect, and the influence of third parties.

- Interest: the status of Kosovo, a political issue, a wholly confronted, conflicting interest, a ‘zero-sum’ solution.

Albanians - full international recognition of independence and further possible relations at the level of two sovereign states.

Serbs - the most comprehensive autonomy, cooperation at the level of state institutions, and ‘temporary institutions in Pristina.'

A possible solution is a reconciliation of interests. Since there is a conflict between the de facto and the desired condition of affairs, it leads to the continuation of the frozen conflict. This position is not suitable for the Albabiabs or Serbs in Kosovo, and the solution can be seen in the relaxation of interests and compromise between the two. Namely, Subotic offers an advanced approach to solving problems, skillfully incorporating the interests of both nations, according to the following:

‘Serbia does not recognize Kosovo but undertakes not to block its admission to international institutions.

(Hypothetical projection)

Serbia and the interim authorities in Pristina have reached a legally binding agreement. Serbia was not required to de jure recognize Kosovo's independence but not to block its membership of Kosovo in international organizations. Thanks to the signed condition that formal recognition of Kosovo's independence will not be necessary for EU membership, Serbia has become a full member of the EU, and so-called Kosovo is starting to open a chapter. Kosovo has changed its constitutional framework to allow for establishing the Union of Serb Municipalities, which has full autonomy in education, culture, language, local self-government, and health care, as envisaged in the so-called Ahtisaari Plus Plan. Serbia no longer opposes Kosovo's membership in international organizations, including membership in the United Nations. Therefore, Serbia has not de jure recognized Kosovo, but the status of Kosovo is no longer a contentious issue in the mutual relations between the two sides’ (Subotić 2021).

Hypothetically, this scenario offers the maximum level of fulfillment of the interests of both parties, leaves neither side in a position of humiliation, enables the progress of all, the development and well-being of the local environment, and extinguishes the accumulated conflict potential. A "Win-Win" solution is a long-term, sustainable, and acceptable solution for everyone.

- Data/information: a dichotomy of truth, information manipulation, wrong and tendentious information, selective and tendentious data, and opposing narrative.

Albanians and Serbs trust only the information they receive from their media or ‘objective’ foreign reporters, provided they support their adopted perception of the truth in the conflict. There is zero tolerance for the smallest, at least extremely well-intentioned, critical attitude that confronts existing stereotypes and generalizations.

Possible solution: achieving the preconditions in connection with stopping, above all, media manipulation and starting to change the narrative towards moderate and further affirmative reports. Mutual opening of newsrooms in national media houses, the functional connection of news agencies and journalist associations. Formation and development of social networks that favor reconciliation and a common future within the region and beyond. Activities supporting the establishment of non-tension reports and confrontational manipulative narratives must be supported by the political, economic, and cultural elites of both nations for the effects to penetrate all structures of society. The strength of the leader's authority, hierarchical affection, and strong collectivity that characterize both nations are the basis that nonstop action in the information field can create a changing environment of understanding the other side, thus reducing existing animosities.

- Third parties: Considering the forms of engagement shown so far, the United States and Germany are the most engaged in actions toward achieving a solution to the conflict in Kosovo. In the escalating phase of the conflict, both sides represented the Albanians. In the current moment of frozen conflict, the actions of the United States and Germany give the impression of striving to resolve the conflict, with a strong position on respecting the status quo and turning to the future.

Albanians and Serbs (de facto and dejure status of Kosovo) put pressure from the authorities on the leaders and elites of both sides. Possible solution: With the support of previously set premises for creating an environment for resolving the conflict in Kosovo (restorative justice, unique truth, and information and uncaptured and safe communication and movement of members of both nations), based on mutual consensus for problem-solving. Both sides have a remarkable capacity for US influence in the necessary direction of the Albanian side and as a guarantor of fulfilling its obligations from the Brussels Agreement (Union of Serbian Municipalities). Germany has a significant role in motivating the Albanian side through the conditional enabling of European integration (first visa liberalization) and Serbia with accelerated accession to the EU. Also, the United States and Germany have the economic power to stimulate development investment funds on both sides.

- Values: the absolute commitment to good and evil is undivided among both peoples. Cohesion within both entities, collectivity, commitment to authority, and low personal preference for pleasures allow the set (negative) value categorization to be multiplied by the actions of opinion leaders. The problem is that the centuries-old, and at the end of the twentieth century, armed escalation conflict has created a physical distance and separation of Albanians and Serbs, which conditions the determination that the other side is badly responsible for everything.

Possible solution: Encouragement of modern and personal preference values based on technology and global media penetration. Through interaction with members of another community, to achieve the penetration of positive thoughts, a view ‘over the wall,' where the general value system is stimulated and facing the fact that belonging to an ethnic community does not mean a negative connotation. The realization of an individual within the traditional culture of his ethnic community does not conflict with the general knowledge of good and evil.

- Relationship: negative experiences from the past, stereotypes, poor and failed communication, repeated negative behaviors.

Possible solution: through prominent examples of restorative justice, promote a uniform attitude towards value systems (‘all crimes are punished,' ‘there are no those protected from justice’). In this way, establish a relationship of trust, where harmful experiences/crimes/crimes are categorized as the actions of specific individuals and not the entire Albanian or Serbian people. That reduces the generalization and the basis for creating negative stereotypes. Implementation requires the support of leaders, political and social elites, and the media.

- Structure: Conflict is fought over the same geographical area, ethnic groups are physically separated and live in parallel realities of conflict awareness, authorities are national leaders who have legitimacy in conflict communications, negotiations on technical issues are sporadic, and negotiating teams have limited powers and dependence from the national leaders.

Possible solution: Present Kosovo as a geographical concept as a space of ordinary life and future for Albanians and Serbs. Insist on the functional competencies of negotiating teams on expert issues related to people's lives. Interested third parties provide constructive support to leaders in achieving a dispersion of responsibility for negotiations on individual issues (health, social protection, education, science, labor) as part of a gradual resolution of the de facto status of Kosovo. Eliminate pressure from negotiators to link every issue, even the most trivial, to Kosovo's status issue.

Conclusion

The longevity and complexity of the Kosovo conflict have had a profound and destructive effect on the Albanian and Serbian people. Considering all the connotations of the conflict, and its ethnic and cultural structure, it is concluded that a rational approach to this problem (de facto and dejure status of Kosovo) must encourage a solution and end the frozen conflict. That is primarily important because of this conflict's destructive escalation potential. Namely, in the turbulent events on the threshold of Europe reflected in the war in Ukraine caused by Russian aggression, it is possible that the great powers (third parties in the Kosovo conflict, primarily the US and Russia) were interested in this war will try to provoke new hotspots to relax their position and secure their negotiating potential. From this aspect, in the long run, it is more beneficial for the Albanian and Serbian people to orient themselves towards solving their problems and not allow them to become instruments in the game of power of the great powers. Getting out of the vortex of prejudices and rationalizing the situation by objectifying the goals of both nations is imperative in the starting points for resolving this ethnonational conflict.

The presented aspects and characteristics of the conflict in Kosovo and a possible model for its resolution are based on a hypothetical model that enables the fulfillment of the optimal level goals of Albanians and Serbs. Also, it is essential to develop an approach that does not lead to a new state of ‘pendulum domination’ through the development of further relations. The state of domination and the absence of constructive communication with disregard for the mutual ethnic, cultural, religious, and social needs of any nation leads to a latent conflict and, in the case of a frozen conflict, to its escalation. In the case of Kosovo, history has shown that domination is an unsustainable concept and leads to a spiral of horror, revenge, and hatred. All state administrations that claimed the legitimacy of governing Kosovo from the end of the nineteenth century until today did not contribute to calming down with their actions; on the contrary, they ignited antagonisms and ethnic intolerance.

The emphasized cohesion of both groups with the affection for authoritarian leadership, as well as the collectivity of Albanians and Serbs, assigns a unique role to the leaders of both nations. Significant responsibility lies with social leaders and opinion leaders of both nations. Therefore, the leaders and elites of both nations must, for the future benefit of Albanians and Serbs, make an effort and support a constructive dialogue, free from the past and turned to the future of both peoples in Kosovo. Only with the expressed visionary courage and visionary leadership lucidity can the intersection of this seemingly insoluble conflict, the Balkan and European Gordian knot, be achieved.

References

- Allport, G. (1954). The Nature of Prejudice. Reading: Addison-Wesley.

- Anastasiou, H. (2008). The broken olive branch: Nationalism, ethnic conflict and the quest for peace in Cyprus. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press.

- Bar-On, D. (2005). “Empirical criteria for reconciliation in practice.” Intervention, 3 (3), pp. 180-191.

- Blagojevic, M. (2000). “The Migration of Serbs from Kosovo during the 1970s and 1980s: Trauma and/or Catharsis.” In Popov, N. (Ed.). The Road to War in Serbia: Trauma and Catharsis. Budapest: Central European University Press.

- Burgess, H. and Burgess, M. G. (1997). Encyclopedia of conflict resolution. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO.

- Deutsch, M. (1958). "Trust and suspicion." Journal of Conflict Resolution, 2 (4), pp. 265–279.

- Duckitt J. (1992). The Social Psychology of Prejudice. New York: Praeger.

- Folger, P. J., Poole, S. M. and Stutman, K. R. (1993). Working through conflict: Strategies for relationships, groups, and organizations (2nd ed.). New York: HarperCollins.

- Furlong, T. G. (2005). The conflict resolution toolbox: models & maps for analyzing, diagnosing, and resolving conflict. Mississauga: John Wiley & Sons Canada.

- Gomez, C. and Taylor, A. K. (2018). “Cultural differences in conflict resolution strategies: A U S–Mexico comparison.” International Journal of Cross-Cultural Management, Vol. 18(1), рр. 33–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470595817747638

- Greenhalgh L. (1986). “Managing Conflict.” Sloan Management Review 27, No. 6, pp. 45–51.

- GRS - The Government of the Republic of Serbia (2013). "Brussels Agreement." https://www.srbija.gov.rs/cinjenice/en/120394, 15/10/2021. (Accessed: 12 Septembre 2022).

- Hofstede Insights (2022). “Compare countries.” Culture Compass. https://www.hofstede-insights.com/fi/product/compare-countries/ (Accessed: May 3, 2022).

- Lewicki, J. R., Barry, B. and Saunders, M. D. (2016). Essentials of negotiation: sixth edition. New York: McGraw-Hill Education.

- Lulzim N. (2018). “The Democratic Values of the Student Movement in Kosovo 1997/1999 and Their Echoes in Western Diplomacy.” Review of European Studies, Vol. 10. No. 2, pp. 167-174.

- Mitrović, M. (2022).“The paper on the strategic communication on the Kosovo-Metohija security issue.” Vojno delo, 2/22, pp. II 127 – II 142. http:/ 0.5937/vojdelo2203127M/

- Nikolić, L. (2003). “Ethnic Prejudices and Discrimination: The Case of Kosovo.” In Bieber, F. and Daskalovski Ž. (Eds.). Understanding the war in Kosovo. London: Frank Cass Publishers, pp. 51-73.

- Nikolic-Ristanovic, V. (2008). “Potential for the use of informal mechanisms and responses to the Kosovo conflict – Serbian perspective.” In Aertsen, I., Arsovska, J., Rohne, H-C., Valinas, M. and Vanspauwen K. (Eds.). Restoring Justice after Large-scale Violent Conflicts. Devon: Willan Publishing, pp. 157-182.

- OUN - United Nations (2006). “UN Handbook on Restorative Justice Programmes.” Vienna: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

- Raduški, N. (1997). “Neke demografske odlike nacionalnih manjina u SRJ Jugoslaviji.” [“Some demographic characteristics of national minorities in FRY Yugoslavia.”] Teme, 20 (3-4), pp. 239-253.

- Rohne, H-C., Arsovska, J. and Aertsen, I. (2008). "Challenging restorative justice - state-based conflict, mass victimization and the changing nature of warfare." In Aertsen, I., Arsovska, J., Rohne, H-C., Valinas, M. and Vanspauwen K. (Eds.). Restoring Justice after Large-scale Violent Conflicts. Devon: Willan Publishing, pp. 3-45.

- Ross, M. H. (2007). Cultural Contestation in Ethnic Conflict. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- RSE - Radio slobodna Evropa (2021). “Vučić i Kurti bez dodirnih tačaka.” ["Vučić and Kurti have no common points."] RSE, 15. Jun 2021. Available at: https://www.slobodnaevropa.org/a/vučić-i-kurti-u-briselu-o-dijalogu-srbije-i-kosova/31306467.html (Accessed: 3 March 2022).

- Sotirovic, B. V. (2014). “Kosovo & Metohija: Ten years after the 'March pogrom' 2004.” Serbian Political Thought, No. 1, year 21, vol. 43, pp. 267-283.

- Stavenhagen R. (1996). Ethnic conflicts and the nation-state. Hampshire, and London: Macmillan Press Ltd./ New York: St. Martin's Press.

- Subotić, M. (2021). “ (Non)Achievability of certain national interests proclaimed by the national security strategy of the Republic of Serbia”, [Милован Суботић, “(Не)Достижност одређених националних интереса прокламованих стратегијом националне безбедности Републике Србије.”] Политика националне безбедности, Година XII, vol. 20, број 1/2021. стр. 55-73. https://doi.org/10.22182/pnb.2012021.4

- Subotić, M. and Mitrović, M. (2018). “Hybrid nature of extremism – cohesive characteristics of ethnonationalism and religious extremism as generators of Balkan insecurity.” Vojno delo, 1/18, pp. 22-33. https://doi.org/10.5937/vojdelo1801022S

- Subotić, R. M. (2017). “Extremism of Kosmete Extremism of Kosmete Albanians: supremacy of ethno-nationalism over religious extremism.” National Interest, Year XIII, vol. 30, No. 3 pp. 221-237. [Суботић, Р. М. “Екстремизам косметских Албанаца: супремација етнонационализма над верским екстремизмом,” Национални интерес/, Година XIII, vol. 30, Број 3, стр. 221-237]. https://doi.org/10.22182/ni.3032017.10

- Subotić, R. M. (2019). "Between Serbian and Orthodox: Nation and confession 800 years after the autocefality of Serbian Orthodox Church.” Culture of Polis (Special edition 2), year XVI, pp. 77-93. [Суботић, Р. М. “Између Српства и Православља: однос нације и конфесије 800 година након признања аутокефалности СПЦ.” Култура полиса, год. XVI, посебно издање 2, стр. 77-93].

- Trbovich, S. A. (2008). A Legal Geography of Yugoslavia’s Disintegration. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Woehrel, S. (1999). “Kosovo: Historical Background to the Current Conflict.” CRS Report for Congress, 3 Јune 1999. https://sgp.fas.org/crs/row/RS20213.pdf (Accessed: June 10, 2022).

- Zdravković, M. (2021). “The causes of the first conflicts between Serbs and Albanians throughout history." National Interest, vol. 40, No. 2, pp.183-204. [Здравковић, М. (2021) “Узроци првих сукоба Срба и Албанаца кроз историју,” Национални интерес, vol. 40, број 2, стр. 183-204]. https://doi.org/10.22182/ni.4022021.8