Prof.dr Alex P.Scmid

The Institute for National and International Security

DOI: https://doi.org/10.37458/ssj.4.1.1

Original Research Paper

Received: December 08, 2022

Accepted: January 27, 2023

Presentation by Alex P. Schmid prepared for the conference “Security Threats and Challenges: East and South-East Europe”, Belgrade, 3 December 2022.

When we talk about European Security, we take it for granted that we all know what “Europe” means. Yet we might not all have the same Europe in mind: is it about the defense of territory or the defense of European values? Almost until the 18th century, our peninsula to the west of Asia, was generally not known as Europe but known as the land of Christendom or Christianity. Only when it began to sink into the minds of more and more people that there was a whole other world out there, beyond the Atlantic and the Urals, and when the new thinking of the enlightenment took broader roots, the peculiar geographic and cultural nature of Europe became more apparent.

Europe has also been defined in non-geographic terms, as manifested in this quote from Paul Hazard in a book which was published in 1935 under the title The Crisis of the European Conscience (1680-1715):

Que’ est-ce l’Europe?

“Une pensée qui ne se contente jamais. Sans pitié pour elle-meme, elle ne cesse jamais de poursuivre deux quétes: l’une ver le bonheur; l’autre, qui lui est plus indispensable encore, et plus chère, vers la vérité. A peine a-t-elle trouve un état qui semble répondre a cette double exigence, elle s’aperçoit, elle sait qu’elle ne tient encore, d’une prise incertaine, que le provisoire, que le relative; et elle recommence la recherce désespéree qui fait sa gloire et son tourment.”[ ]

The search for a special form of well-being called happiness in this world rather than in a heavenly paradise, we find, of course not only in the Europe of the enlightenment but also in the American Declaration of Independence of 1776 which speaks of “Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness”.

While this search for happiness is continuing unabated, the search for truth – which is the hallmark of science – is under pressure, certainly in the United States where there is talk of a “truth decay” through “alternative facts” and some even talk about a “post-truth age”. Here in Europe, the war of aggression against Ukraine has again brought home to many of us the truth that defense is not just about territory but also, and perhaps foremost, about values. War crimes against civilians are committed there on a large scale by the aggressor. Is that so different from terrorism? Thirty years ago, in a report for the UN Crime Commission, I proposed to define acts of terrorism as “the peacetime equivalent of war crimes”. [ ] There are hundreds of definitions of terrorism. [ ] In the following presentation I will use two definitions, one from the social sciences, namely from the Global Terrorism Index Definition of Terrorism (Australia):

“The systemic threat or use of violence, whether for or in opposition to established authority, with the intention of communicating a political, religious or ideological message to a group larger than the victim group by generating fear and altering the behaviour of the larger group”. [ ]

….and one more legal in nature, namely from the European Union:

"Terrorist acts" mean intentional acts which, given their nature or context, may seriously damage a country or international organisation and which are defined as an offence under national law. These include:

- attacks upon a person's life which may cause death

- attacks upon the physical integrity of a person

- kidnapping or hostage taking

- causing extensive destruction to a Government or public facility, a transport system, an infrastructure facility

- seizure of aircraft, ships or other means of public or goods transport(…)

In order for these acts to constitute terrorist acts, they must be carried out with the aim of seriously intimidating a population, or unduly compelling a Government or an international organisation to perform or abstain from performing any act, or seriously destabilising or destroying the fundamental political, constitutional, economic or social structures of a country or an international organisation”. [ ]

Since the attacks of 9/11 and the declaration of a Global War on Terror (GWOT) by the United States, we have been made to believe that terrorism is global. However, far from all countries have been directly affected by non-state terrorism in recent years. Last year, for instance, 105 countries had experienced no terrorism and another 44 countries had fewer than 25 deaths from terrorism. [ ]

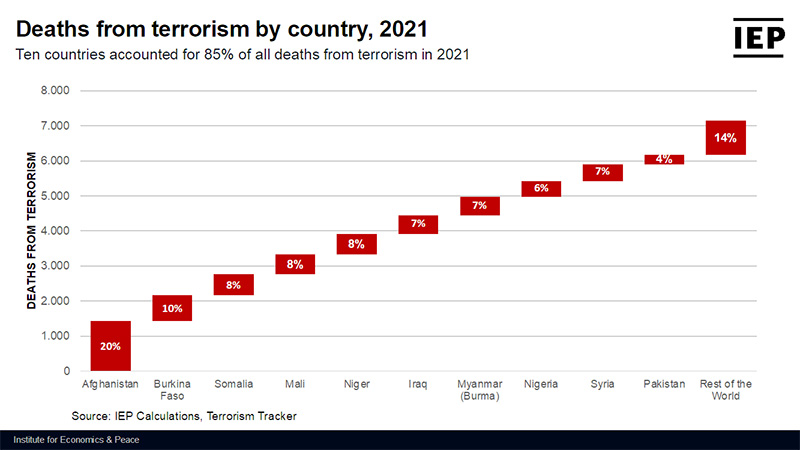

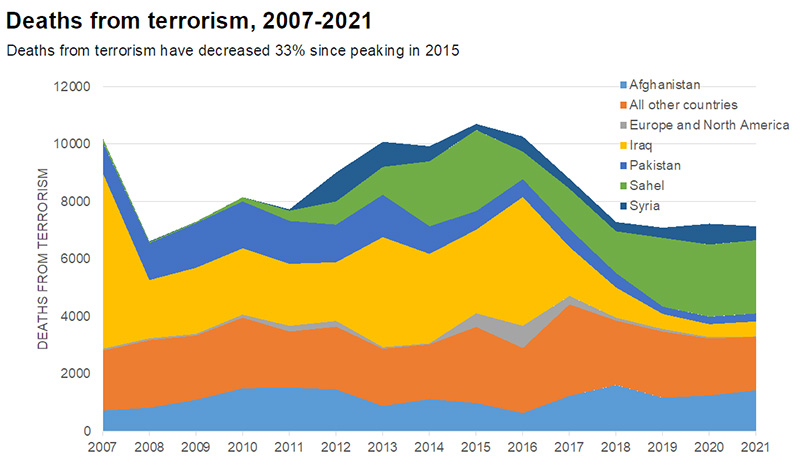

Like war crimes are generally related to civil and inter-state wars, most acts of terrorism are closely related to countries involved in minor or major domestic armed conflicts, as this graph from the Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP) makes clear:

If we look at the death toll of terrorism, it is evident that most deaths occur outside Europe. Last year, for instance, ten countries accounted for 85 percent of all terrorist deaths. Most of them happen to be Muslim majority countries.

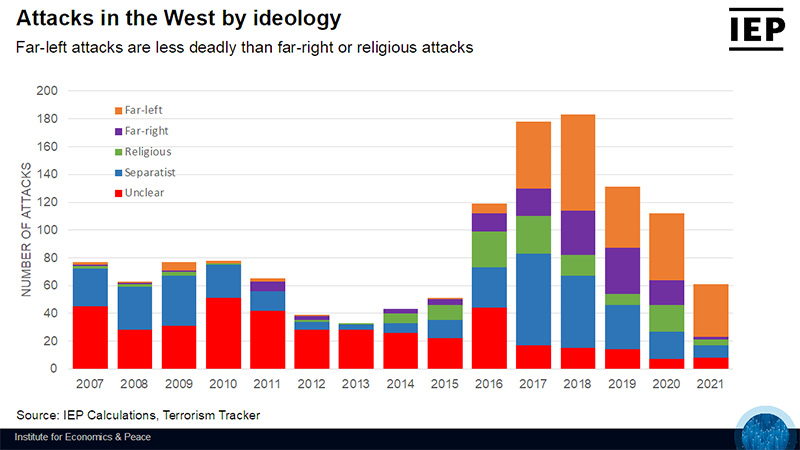

In terms of ideology, we see that religious terrorism is still by far the deadliest form of terrorism, followed more recently by right-wing terrorism which is often a reaction to Islamist extremism:

If we now turn our focus on the Western world, this ideological distribution breaks down in the following way:

Interesting in this graph is the category “unclear”. Partly this is because almost half of all attacks labelled “terrorist” are unclaimed, and partly this is due to many lone actor terrorists not belonging to a specific group. Such lone terrorists often adhere to a å-la-carte ideology. Some of these “lone wolves” also have mental health problems. In a recent analysis of “The Evolving Terrorism Threat in Europe”, Raffaello Pantucci noted:

“Perpetrators no longer seemed to have a coherent motivation based on only one ideology (or any external direction), but often related highly idiosyncratic ideologies that pulled in ideas from a wide range of sources (…) In the UK…the Home Office created an entirely new category, labelling a growing number of cases as originating in ‘mixed, unstable, or unclear’ ideology, as distinct from the more classical left-wing, right-wing, and violent Islamist ideologies”.[ ]

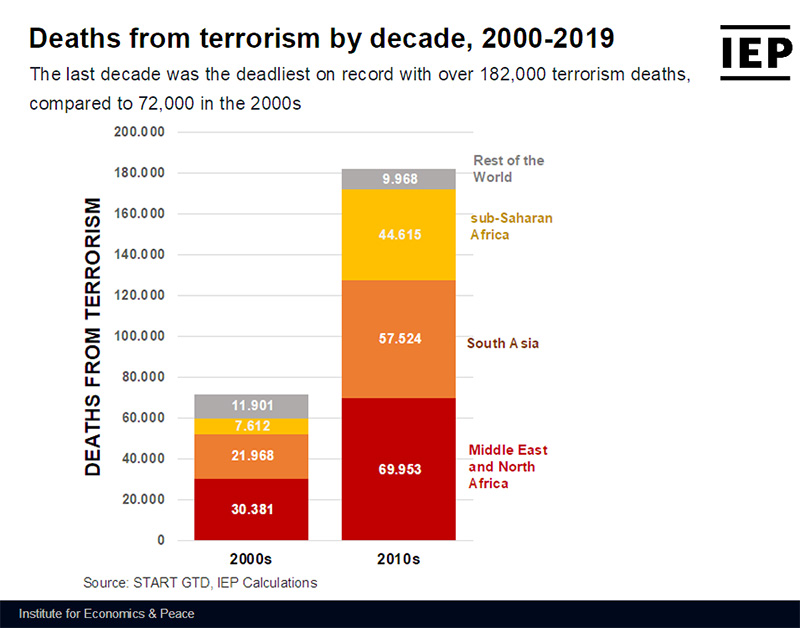

Compared to other parts of the world, Europe has been only a minor theatre of terrorist attacks. In this graph, Europe does not even have a category of its own but is subsumed in “Rest of the World”:

No European country figures among the top ten of countries affected most by acts of terrorism. These countries are all in the Middle East and Asia and in Africa, the majority of them Muslim-majority countries.

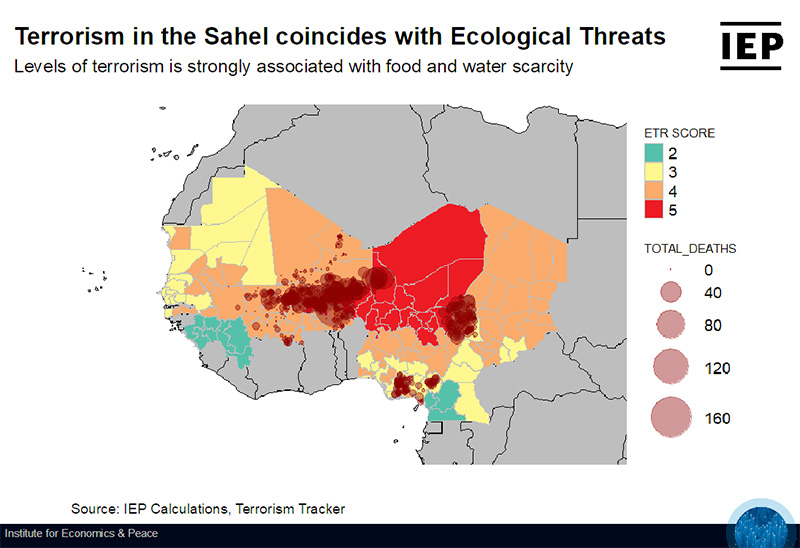

The Sahel region has become the new epicentrum of non-state terrorism, with ten times more deaths from terrorism than fifteen years ago, in 2007. High fertility rates, desertification and other natural and man-made disasters have contributed to this crisis situation.

Last year, thanks to some successes of the Nigerian government against Boko Haram, deaths in the Sahel region declined by ten percent. There has also been some reduction in the Middle East and North Africa where terrorism declined 14 percent from 2020 to 2021. Worldwide, deaths from terrorism have also declined in the last four years, hovering now between 7.100 and 7.300 people killed even though the number of attacks increased between 2020 and 2021 and stand at 5.226 attacks.[ ]

Nevertheless, there is a significant decline compared to the peak years of 2014 and 2015 when the global death toll from terrorism was much higher, especially in Syria and Iraq.[ ] The main perpetrator at that time was the Islamic State which even last year managed to kill more than two thousand (2,066) persons in 20 countries.[ ]

As can be seen from the following graph: attacks in the West – Europe and North America - the grey ribbon in the middle on this graph - have fallen for the last four years by 70 percent, with 59 attacks but only 10 deaths in 2021.

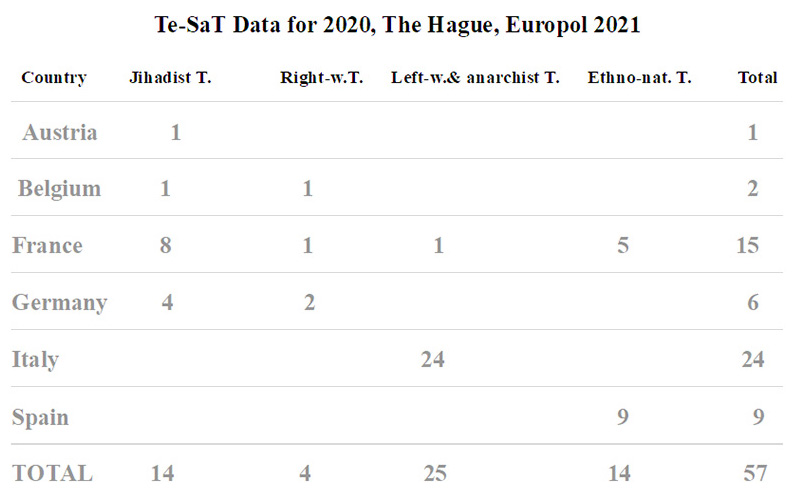

Let me now turn to Europe, looking at EUROPOL’s overview of failed, foiled and completed attacks.[ ]

Since 2019 completed, foiled or failed attacks by jihadists in Europe fell from 18 to 14 in 2020 and to 11 in 2021. In the same period, right-wing attacks changed from 2 to 4 to 3. Left-wing and anarchist attacks decreased from 26 in 2019 to 25 in 2020 and 19 in 2021. Ethno-nationalist and separatist attacks increased from 1 to 14 and then dropped to zero. There were 2 other attacks in 2019 and 6 non-specified attacks in the same year. The total number of terrorist attacks changed from 55 in 2019 to 57 in 2020 and further declined to 15 in 2021.

For the Balkan region, Europol registered only one attack: “On 19 April 2021, a 34-year-old Albanian citizen was arrested on charges of terrorism, after having stabbed five people in a mosque in Tirana”.[ ].

The Europol figures reflect, on the one hand, a diminished terrorist threat and, on the other hand, also the success of prevention and pre-emption. There has been a hight number of arrests in recent years – 260 suspects were arrested in 2021 and 254 in 2020 and 436 in 2019. [ ]

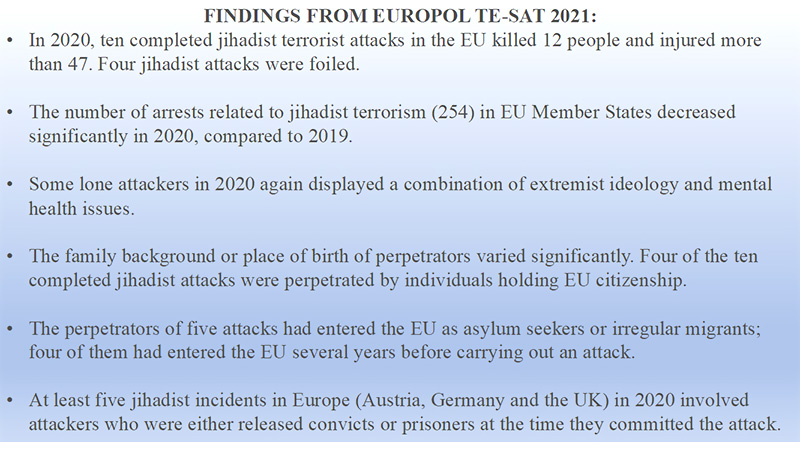

Here are some more findings from the EUROPOL Terrorism Situation and Trend report[ ]:

If we turn for a moment to the academic literature covering a longer period of time, the following picture emerges, based on an analysis of 151 jihadist plots in Western Europe between mid-1994 and mid-2015:” ….as much as 70 percent of the plots involving single actors went undetected and reached the execution stage, while group-based plots were foiled in almost 80 percent of cases”.[ ]

A study by the Dutch intelligence service AIVD, surveying 112 jihadist incidents between 2004 and 2018, concluded that 85 percent of the attacks were directed at soft targets with little or no surrounding security measures. Only 5 percent of all attacks targeted well-protected (hard) targets while 8 percent of the targets had some form of access control (e.g. entry tickets and bag checks) and 12 percent of the targets were under the physical protection of police officers or the military.[ ]

These days, most attacks in Europe are the work of lone actors who are, however, part of social media-based extremist transnational networks. Without greater internet surveillance and new rules regarding limiting end-to-end encryption of mobile phones, such persons are difficult to identify and arrest in time. A growing threat is the rise of anti-establishment and anti-government violence which in most cases has not yet take the form of terrorism but manifests itself in hate campaigns resulting in targeted assassinations of both national and local politicians.[ ]

What is not yet reflected in published Europol information is the recent situation in the Ukraine in the last nine months. Some acts of non-state terrorism in the Ukraine might be hidden by the fog of war. However, contrary to other ongoings wars like those in Ethiopia or Yemen, the war in the Ukraine has received ample coverage in both mass and social media, What emerges from these reports is that the Russian invasion has increasingly focused on attacking civilian infrastructures, with the number of civilians killed and injured going into the thousands and the numbers of displaced persons going into the millions. In peace time, much of that sort of unprovoked violence against unarmed civilians would be termed terrorism. Unable to achieve a military victory against the armed forces of the Ukraine, President Putin has apparently decided to terrorise the Ukrainian people by destroying electricity networks and other civilian infrastructure, in the hope that “comrade winter” will bring the government of Ukraine accept his conditions for peace.

In the light of this new tactic, the European parliament adopted on 23 November 2022, a resolution declaring Russia to be a “terrorism-sponsoring state”.[ ]. The issue of state terrorism was also brought before the Security Council of the United Nations which was addressed by Volodymyr Zelenskyy. He said on November 23, 2022:

"Today is just one day, but we have received 70 missiles. That's the Russian formula of terror," Zelenskyy said via video link to the Council chamber in New York. He said hospitals, schools, transport infrastructure and residential areas had all been hit. "When we have the temperature below zero, and millions of people without energy supplies, without heating, without water, this is an obvious crime against humanity."

In his speech, Zelenskyy called for the adoption of a UN resolution condemning energy terror. Ukraine is waiting to see "a very firm reaction" to Wednesday's airstrikes from the world, he added.(…) "We cannot be hostage to one international terrorist," he said. "Russia is doing everything to make an energy generator a more powerful tool than the UN Charter."[ ]

The repercussions of this war of aggression are felt worldwide, resulting, inter alia, in food insecurity in Africa and energy insecurity in much of Europe.

Non-Terrorist Threats to European Security

This brings me to non-terrorist threats which Europe and, to varying extents, parts of the rest of the world are currently facing.

There are many insecurities that worry people these days. They tend to fall into one of these three categories introduced by a former US Secretary of Defense, Donald Rumsfeld in 2002 [ ]:

(i) there are things we know we know.

(ii) We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say, we know there are some things we do not know.

(iii) But there are also unknown unknowns – the ones we don’t know we don’t know”.

Here I will focus only on a few of the areas/threats that “we know we know”. I will leave out the COVID-pandemic which has still not run its course and currently haunts mainland China where it originated from.

What are some of the major security problems we face now and in the near future? To find out, I consulted a few “doom” books. Here are some of the threats I found in a work by Alok Jha: 50 Ways the World Could End (2011):

- Human Threats: include Global Pandemic, Mutually Assured [Nuclear] Destruction, Overpopulation

Tech Threats: include Cyberwar, Biotech Disaster, Artificial Superintelligence

- Environmental Threats: include Death of the Bees, Desert Earth, Global Food Crisis, Water Wars, Rising Sea Levels, The Gulf Stream Shuts Down, Ozon Destruction, Asteroid Impact, Mega Tsunami, Supervulcano, Oxygen Depletion, Geomagnetic Reversal, Superstroms

- Space-based Threats: include Sun Storms, Gamma Rays from Space, Hostile Extraterrestrials, Death of the Sun, Galactic Collision

- Genetic Threats: include Organic Cell Disintegration.

Some of these threats are in the very distant future, e.g., the Galactic Collision of our galaxy with Andromeda which is still many light years away. So far astronomers have catalogued 200,000 galaxies of an estimated total of 100 billion galaxies out there beyond our own Milky Way. We cannot do anything about such interstellar natural security threats. We are not even able to control earthquakes which have killed hundreds of thousands of people in the last century alone. [ ]

However, other threats to our safety and security on this list can be reduced by human intervention. For instance, there has, through collective international action, been some success in shrinking the size of the Antarctic Ozon hole from a peak in the early 2000s so that we are less exposed to dangerous levels of ultraviolent light [ ]. What is striking is that almost all the threats on this list have little or nothing to do with national security since these are in most cases planetary threats crossing manmade borders.

We can, however, do something against some other threats on this list – for instance, the threat of overpopulation. When I was born in 1943 our planet had fewer than two billion people. Last month we passed the eight billion mark and until 2050 we are likely to reach, according to the UN Population Division, close to ten billion people [ ]. Most of the 120 million babies born each year will be born in the global south, mainly in Africa.[ ]

Population growth not only leads to the depletion of natural resources and rises in the cost of living but also tends to translate into social tensions and international migration pressure.

Mass migration also features as a security threat in the following list which is based on another doomsday book: Joel Levy’s Scenarios for the End of the World (2005):

- The Frankenstein Effect: including Pandemic, Superbug, Rogue AI, Physics experiment gone wrong

- Threat of Third World War: incl. Terror unlimited, Extremism and Fundamentalism, Mass Migrations

- Threat of Ecocide: incl. Poisoning the Planet, the Parched Earth, the Barren Land; The Starving Ocean, Acid Sea

- Threat of Climate Change: incl. Global Warming, a New Ice Age

- Threat of Cataclysm: incl. Comet and Asteroid Impacts; Super-volcano, Mega-Tsunami; Reversal of the Poles; Cosmological Catastrophes.

Let me offer you a few observations on migration. While Western and Central European countries have this year welcomed more than seven million people from Ukraine, the welcome in 2015/16 of roughly one million Syrians – many of whom had also fled Russian bombardments – was less enthusiastic. Today Europe sees new refugee flows involving hundreds of thousands of people from places like Afghanistan but also from countries with less repressive regimes like Tunisia, Bangladesh and India – and, partly thanks to the visa-free travel to Serbia – also from Burundi.[ ] Last October, the number of “irregular border-crossings” into the EU stood at 281,000 people for 2022– an increase of 77 percent compared to the year before. It is likely to cross the 300,000 mark before the end of 2022.

This largely uncontrolled immigration has fed conspiracy theory talk about The Great Replacement – white people becoming a minority in their own land. Some mainstream populist politicians in the West have adopted variations of this greatly exaggerated replacement theme. In some European countries irregular immigration is indeed back to levels last seen in 2015/16. However, on average, Europe received only about 500,000 asylum seekers each year - which is about one tenth of one percent of the total population of the European Union – something that should be easily manageable if there was enough solidarity with frontier countries like Italy and Greece – countries which bear the major burden.

In the future we might see much bigger challenges. Currently the number of immigrants is around 20 percent in many countries on our continent (Austria: 19%, Germany:19%, Sweden: 20%, Switzerland: 29%)[ ]. Immigration is, in most cases, becoming a major problem only if and when integration fails – something which can be dealt with by intensive civic education courses for newcomers.

If climate-induced migration in the years ahead is taken into account, many more people are likely to seek salvation on our shores. Climate change induced migration is likely to be massive. One UN estimate suggests that water stress alone could displace 700 million people by as early as 2030.[ ] Many of these people might head for the global north, including Europe, creating stress and resistance, exaggerated by the rhetoric of populist politicians.

A third work I consulted is “Global Catastrophic Risks” (2008), edited by Nick Bostrom and Milan M. Cirovic. [ ]. It lists some of the same threats as the other two doom authors but also introduces new ones.

- Environmental Threats: including Drastic and Rapid Climate Change; Volcanic Winter; Solar flares; Cosmic Rays from nearby supernovae

- Plagues and Pandemics: including Microbes that threaten without infection; man-made viruses

- Technical failure: including Runaway technologies

- War: including Continuing threat of nuclear war; nuclear winter

- Bio- and Nano-Technology: including biological weapons; creating novel pathogens; nano-built weaponry.

- Totalitarian Threat: including Stable Totalitarianism

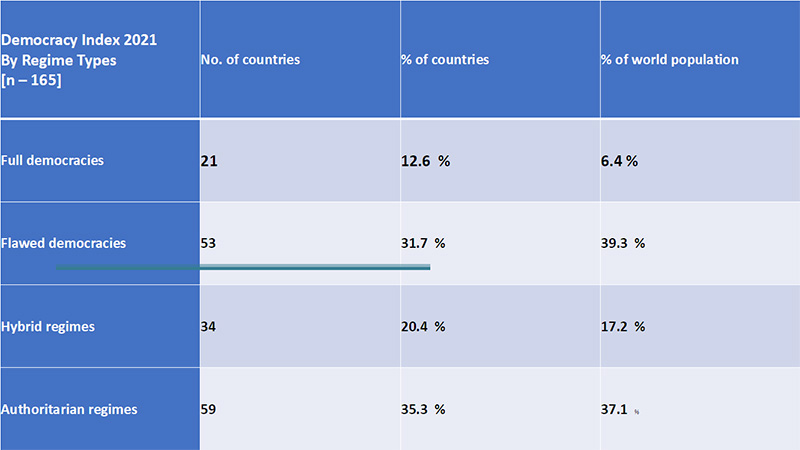

From this third doom scenario book I would like to pick the last item, the totalitarian threat for closer consideration. Totalitarian regimes – contrary to authoritarian regimes – have in the past tended to have a short life span.[ ] However, this might be changing due to the widespread use of new surveillance and repression technologies. While after the end of the Cold War the number of democracies increased to 120 by the year 2000, there has been a reversal of the trend, leading to a new authoritarianism and, in some cases, even totalitarianism since 2010 - the aftermath of the global financial crisis of 2008.

This is important for international security. Liberal democracies generally do not attack other democracies, [ ] although they might attack non-democracies. That is one of the few well-documented rules in international relations theory. Autocracies and totalitarian regimes are generally much more aggressive than democracies, threatening not only the human security of their own citizens but also the national security of their neighbours.

Let us look at the figures. The following table is from The Economist’s annual democracy index [ ], reflecting the situation in 2021, and is based on 165 countries:

According to this table, less than half of the world’s population lives in some sort of a democracy, and less than seven percent of all people on earth live in a “full democracy”. There are, according to this count, only 21“full democracies”. 53 democracies are “flawed democracies” while another 34 are classified as “hybrid democracies”.[ ] Some of the 59 “authoritarian regimes” have since 2021 moved closer towards “totalitarian regimes”. This includes Russia and China - next to smaller rogue regimes which rule with an iron fist – countries like North Korea and Iran. Worldwide, democracy is “in recession”. In the last 15 years two thirds of the countries covered by the Economist’s Democracy Index (108 countries) [ ] have seen a decline of their standing based on the five indicators of the Democracy Index. This includes 19 out of 21 countries in Western Europe where both civil liberties and trust in government have been eroded, partly due to their handling of the COVID pandemic. The consequences of this are profound for both human security and national security as well as for global governance - the security of the international system.

Are the institutions designed to secure global order in 1945 still up to their task? Winston Churchill once said that: “democracy is the worst form of government – except for all the others that have been tried.”[ ] The same can be said about the liberal international order that came into existence in 1945 with the creation of the United Nations and its sister institutions, the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. Flawed as this security system is, the alternatives currently on the horizon are worse. The United States seems to be no longer willing and able to defend the rule-based international order created in1945. The European Union is still too divided to play a bigger role and Russia is too weak and still ruled by former KGB figures. Yet a new world order “with Chinese characteristics” shaped by China’s Communist Party appears to be much worse than the present US-led international order which was created at the end of the Second World War.

We have entered period of instability and insecurity. What happens in states where elites cannot be replaced by honest democratic elections is that the ruling class tends to become predatory, seeing the state as its public instrument to enrich themselves privately. China, for instance, has one of the world’s most unequal wealth distribution – worse than the United States [ ], despite being run by a Communist Party that pretends to adhere to an egalitarian ideology. In a growing number of states there are close ties between organised crime and government and some political leaders in fact not only act like criminals but are gangsters. [ ] In order to prosecute their enemies, not only at home but also abroad, they use legitimate international instruments like Interpol’s arrest warrant to go after them - if they do not send their own agents or hired killers to murder them in foreign lands.

Many citizens have lost faith in the ability of their governments to guarantee their security. Rich citizens and corporations have increasingly turned to private security services to protect them. Private security is now a 24 billion dollar business [ ] The inequality in the world has increased. Half of the world’s population – four billion people - live on US $ 5.50 a day (while twenty years ago the share of those having to live on less than $2 a day was 2.8 billion).Three billion people cannot afford a healthy diet. Such misery and inequality nourishes a sense of revolt on the one hand and a desire for harsh repression by the elite that has captured the state on the other hand. It also leads to voluntary and involuntary migration. In the year 2000 there were 173 million international migrants. Today, there are 281 million, or 3.6 percent of the world population. Global forced displacement rose from 22.3 million people in the year 200 to 79.5 million in 2020. According to one database, the number of state-based armed conflicts rose from 37 in 2000 to 54 in 2019, including 7 wars [ ] Other databases suggest even higher figures.

The Heidelberg Institute for International Conflict Research, which monitors disputes, non-violent crises, violent crises, limited wars and wars, publishes since 1990 an annual Conflict Barometer. It recorded for the year 2021 355 conflicts worldwide, of which 204 were fought violently while 151 were fought out without recourse to violence. For 2021, the Conflict Barometer recorded, next to 20 limited wars, 20 full wars - one less than in 2020 but still the second highest number of wars ever documented in three decades of monitoring conflicts.[ ]

Is there no hope left? Yes, there is: science can help enormously to solve threats to our security as the response of the global scientific community to the COVID-19 pandemic has shown. If we fully harness the power of science to deal with global warming and with other challenges facing us - then there is indeed hope. If we listen to populist demagogues spreading conspiracy theories that put the blame for things that have gone wrong on one or another scapegoat, who in their view needs to be physically destroyed, we will be lost. For science to triumph over simplistic pseudo-solutions, the efforts of all of us are called for. I hope that the Institute for National and International Security and its international network are going to play an important role in this.

References

- Bostrom, Nick and Milan M. Cirkovic. (Eds.) Global Catastrophic Risks. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

- European Union. Document 32001E0931 Article 1(3) of Common Position 2001/931/CFSP. URL: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32001E0931

- Europol. European Union .Terrorism Situation and Trend Report, Luxembourg, Publications Office of the European Union, 2022.

- Ferguson, Niall. Doom. The Politics of Catastrophe. Penguin Press, 2021.

- Gardener, Dan. Risk. The Science and Politics of Fear. London: Virgin Books, 2008.

- Institute for Economics & Peace. Global Terrorism Index 2022: Measuring the Impact of Terrorism, Sydney, March 2022. URL: http://visionofhumanity.org/resources.

- Jha. Alok 50 Ways the World Could End. London: Quercus, 2014.

- Levy, Joel. The Doomsday Book. Scenarios for the End of the World. London: Vision Paperbacks, 2005.

Notes

[1 ] [Translated from French: “A way of thinking that is never satisfied. Without mercy for itself, it never ceases to pursue two objectives: one towards happiness; the other, which is even more indispensable to it and more precious, towards truth. Hardly has it found a state [of equilibrium] which seems to (co-)respond to these two requirements, it becomes aware that it is not yet there, that it is still uncertain, provisional and relative; and it resumes the desperate search which is both its glory and its torment”. - Paul Hazard. La crise de la conscience europeenne (1680-1715). Vol. II, pp. 279-296. Paris, 1935.

[2 ] Alex P. Schmid. The Definition of Terrorism. A Study in Compliance with CTL/9/91/2207 for the U.N. Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice Branch. Leiden: Center for the Study of Social Conflicts, December 1992, p. 9.

[3 ] Cf. Alex P. Schmid. Handbook of Terrorism Research. New York and London: Routledge, 2011, where 260 definitions are listed.

[4 ] Institute for Economics & Peace [IEP]. Global Terrorism Index 2022: Measuring the Impact of Terrorism, Sydney,I EP, March 2022, p. 6 URL: http://visionofhumanity.org/resources. The definition is based on the source of data utilised by this Australian institute: data generated for the US government by the University of Maryland (START) and, more recently, by the George Mason University, Fairfax County, Virginia.

[5 ] Article 1(3) of Common Position 2001/931/CFSP sets out the meaning of "terrorist act". See: European Union. Document 32001E0931 Article 1(3) of Common Position 2001/931/CFSP. URL: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32001E0931

[6 ] IEP, p.6.

[7 ] Raffaello Pantucci. The Evolving Terrorism Threat in Europe. Current History, March 2022, p.102 and p.106.

[8 ] All data from Global Terrorism Index (GTI). Some other estimates are higher. According to the US State Department, basing itself on data collected by George Mason university, there were in 2021, 10,17 terrorist incidents, resulting in 29,389 fatalities and 18,413 wounded, in addition to 4,471 kidnappings. See: Country Reports on Terrorism 2020, p.5; October 29, 2021 Prepared for U.S. Department of State Bureau of Counterterrorism. URL: www.dsgonline.com

[9 ] Terrorism by Hannah Ritchie, Joe Hasell, Edouard Mathieu, Cameron Appel and Max Roser

URL:https://ourworldindata.org/team .

[10 ] GTI, op. cit.

[ 11] Europol TE-SAT 2022, pp.8-9.- These figures exclude post-Brexit Great Britain (62 incidents) and non-EU Switzerland (2 probably terrorist incidents)

[12 ] Europol TE-SAT 2022, pp. 36-37.

[13 ] Europol TE-SAT 2022, p. 9.

[14 ] Europol, TE-SAT, 2021, data for 2020, p. 42.

[15 ] Petter Nesser. Islamist Terrorism in Europe. A History. London: Hurst, 2016, pp. 59-60.

[ 16 ]Algemene Inlichtingen- en Veiligheidsdienst. Insights into targets. Fifteen years of jihadist attacks in the West. The Hague: AIVD, 2019, p. 20.

17 Cf. Special Issue of Perspectives on Terrorism, Vol. XVI, Issue 6, December 2022, guest-edited by Tore Bjørgo and Kurt Braddock .

[18 ] 494 votes were in favour, 58 votes against and the resolution, with 44 abstentions.URL: https://t.co/zyspaI9ng8. The European parliament’s resolution stated:” “The deliberate attacks and atrocities committed by Russian forces and their proxies against civilians in Ukraine, the destruction of civilian infrastructure and other serious violations of international and humanitarian law amount to acts of terror and constitute war crimes”. - Cit. Al Jazeera, 25 November 2022.

[19 ] Deutsche Welle, 23 November 2022; URL: www.dw.com .

[20 ] Niall Ferguson. Doom. The Politics of Catastrophe. Penguin, 2021, p.356.

[21 ] Cf. Niall Ferguson. Doom. The Politics of Catastrophe. Penguin Books, 2021, pp.87-88.

22 Cf. URL: U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration 26 October 2022. Antarctic Ozon Hole slightly smaller in 2022. URL: https://www.noaa.gov/news-release/antarctic-ozone-hole-slightly-smaller-in-2022 .

23]According to the projections of the UN Population Division, the estimate for 2050 is 9.7 billion people.

[24 ] IHME, Global Burden of Disease (2019); URL: www.worldometers.info .

[25 ] The Economist,19th November 2022, p.29. 40 percent of the irregular immigrants come via the airport of Belgrade. – Die Presse, 25 November 2022.

[26 ] Nick Routley. Countries with the Highest (and Lowest) Proportion of Immigrants. Visual Capitalist ,22 November 2022; URL: www.Visualcapitalist.com. Data based in Source: UN via World Population Review.

[27 ]Eamonn Noonan with Ana Rusu, Strategic Foresight and Capabilities Unit PE 729.334 – March 2022. European Parliamentary Research Service. The Future of Climate Change. URL: europarl.europa.eu

[28 ] Nick Bostrom and Milan M. Cirkovic. Global Catastrophic Risks. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

[29 ] Idem, p.507.

[30 ] The democratic peace thesis – that liberal democracies do not attack other democracies, has strong empirical support in international relations research. Cf. Rummel, Rudolph J. (1997). Power Kills: Democracy as a Method of Nonviolence. New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers.Some critics argue that peace causes democracy rather than the other way round.

[31 ] The Economist’s Democracy Index is based on five categories: electoral process and pluralism, functioning of government, political participation, political culture, and civil liberties. Based on its scores on a range of indicators within these categories, each country is then classified as one of four types of regime: “full democracy”, “flawed democracy”, “hybrid regime” or “authoritarian regime”. The Index excludes micro-states - countries with fewer than one million inhabitants.

[32 ] The Economist. Democracy Index 2021.The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2022, p.4; URL: www.eiu.com .

[33 ] Larry Diamond coined the phrase “democratic recession” to describe the global retreat of democracy since 2006 (Journal of Democracy, Vol 26, Issue 1, January 2015).

34 Winston S. Churchill in House of Parliament, 1947.

[35 ] Lili Pike. Chinas economic inequality is worse than America’s. URL: grid.news. 26 July 2022.

[36 ] Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime. The Global Illicit Economy: Trajectories of Transnational Organized Crime. Geneva, March 2021: “There is a common perception in many countries, be they democracies or autocracies, that the ruling class uses public resources and systems to enrich themselves, while ignoring the interests of citizens.”, p.52.

[37 ] Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime. The Global Illicit Economy: Trajectories of Transnational Organized Crime. Geneva, March 2021, p. 100 (URL:www.globalinitiative.net): “But just as criminal groups are splintering and fortifying with weapons, so too is the global security framework. One result has been the growth in the global market for private security services (PSS), which includes private guarding, surveillance and armed transport, now worth an estimated US$24 billion. These fractured security structures blend private and public regimes, national and international actors, and are ripe for corruption and violence – and even criminal group infiltration – as transparency shrinks.”

[38 ] Cf. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/the-number-of-active-state-based-conflicts?country=~OWID_WRL .

[39 ] Heidelberg Institute for International Conflict Research. Heidelberg Conflict Barometer 2021 Disputes, Non-Violent Crises, Violent Crises, Limited Wars, Wars. Heidelberg: HIIK, 2022, p.15. URL: www.hiik.de