Acculturation as an Instrument for Minimalization of Security Risks resulting From Immigration

(No. 1, 2021. Security Science Journal)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.37458/ssj.2.1.6

Author: Prof.dr Rastislav Kazansky

Abstract:

The paper focuses on various concepts deepening the term of „security“, on the Copenhagen school concept of societal sector of security, but also human security and the application of the acculturation theory. Human security is a concept, in which the deepening of contents of the term „security“ goes from a macro-level to a micro-level. The traditional concept of security takes into account only the state level and understands threats only to the state in itself, whereas human security redirects the attention towards the individual people. Societal sector, on the other hand, speaks of non-military threats to society and deepens the security concept even further. Based on the assumption, that the extent of risks to the receiving state depends on the effectiveness of incorporation of immigrants, the goal of the article is to apply the acculturation to the process of incorporation of immigrants into the majority population in order to minimize the negative impacts stemming from immigration.

Key words: immigration, security, acculturation, risks, incorporation, integration

INTRODUCTION

The current dynamic and at the same time turbulent development of human civilization brings, in addition to many positives, also several negatives, which are manifested in various areas of human life and the whole society (Ivančík, 2012). The deepening of economic, political, social, security and other activities across national borders because of increasing globalization processes subsequently brings, together with the growing interconnectedness of actors of those processes and the weakening of time and space barriers, various problems and challenges, which today's society must deal with (Ivančík, Baričičová, 2020).

The analyzed security concepts are concerned

with deepening the traditional understanding of the term and it will be the concept of human security and concept of societal sector of security, whose agenda is the closest to the issues of social incorporation in the immigration context. Consequently, we will move on to the theory of acculturation, what it means, what are its models and how it could be helpful for making the absorption of immigrants more effective and for better coexistence of all people in society.

It is our understanding, that the society is broken with aversions and tension, when there is a several parallel cultures or communities present, which do not understand that all are actually pulling on the same rope. In these situations, immigrants do not try to actively contribute to the society, because they are under impression, that the society rejects them and vice versa, majority society rejects them, because it’s under impression, that the immigrants are not interested in it. Should the result of the integration policies is not the absence of division to us and them, the strong communities of immigrants might represent security risks to the society.

1. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK OF THE CONCEPTS OF HUMAN SECURITY AND SOCIETAL SECTOR OF SECURITY

The first step for ou research is to start withe the theoretical framework – the definition of security. Security is Science about the condition of state and processes within the state, specifically, condition and processes which enable normal functioning of state and development.That condition is depending on internal and external risk/s. Security Science is based on theories of State and Law, the theory of Conflicts, the theory of Complex Systems as well as the theories of Catastrophe.

Starting from Plato Ideal Society within the Ideal States to Tomas Hobs and his description of the Natural condition of Mankind and Natural Laws and Contract.Security Science uses all social scientific methods and besides that, a spe-cial scientific methodology that is different from all other social sciences. It is a methodology used in the collection, processing, and analysis of data as well as the methodology of predictions. All of these specific methods coming from Natural Science.Security Science is indivisible but it can be viewed from several aspects such as environmental security, nuclear, energy, economic, legal security, and so on. In all these aspects of security it is a case about variety of conditions of the state as ordered society. In all of those aspects fact remain that it is a case of basic or fundamental conditions which determine normal function and development of society as whole. Whether it is a case of state or society at the national or international level, Security Science study, follow and monitor all the processes and phenomena that affect the aforementioned conditions. (Todorović, Trifunović, 2020) One of the important security phenomenom is a international migration.

We dare to argue, that the multidisciplinarity of international migration reflects the trend of deepening the traditional concept of security. The fact, that it could be perceived through the prism of international relations, geography, political science, sociology, demography, or other disciplines is in accord with all the fields in which we can find threats and risks resulting from migration. This inherently relates to the concept of human security, which was underlined by the Resolution 66/290 of General Assembly which defined it as an approach, which should help all the member states in identificating and addressing the challenges concerned with survival, livelyhood and dignity of their citizens. It calls to people-focused, complex, context-specific and prevention-oriented answers, which strengthen protection and status of all people (United Nations Trust Fund for Human Security, 2021). This definition, however, is too vague and it’s more closely described by Catia Gregoratti, who argues, that human security is an approach to national and international security, which gives priority on human beings and their complex social and economic interactions (Gregoratti, 2021). Thus, it is essential to perceive human security as a certain – relatively new – paradigm in international relations and security studies, which focuses its attention to a micro-level, so to speak. It doesn’t see only the prism of what could hurt a state, but of all that, which could hurt an individual. Therefore, with this category we could cover even poverty or diseases. As Gregoratti says: central to this approach is the understanding that as the lack of human security can undermine peace and stability inside or between states, even the excessive emphasis on state security may be harmful for human well-being (Gregoratti, 2021). Nevertheless, the first ever mention of human security can be found in a document from 1994, Human Development Report 1994 published by United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Although it evades the specific definition with the argument that as a concept of human freedom, human security is more easily defined by its absence than its presence (UNDP, 1994: 23), it puts forward 7 categories which should, in general cover all threats that exist for human security. They are:

- Economic security

- Food security

- Health security

- Environmental Security

- Personal security

- Community security

- Political security

We could consider secured basic income as a condition of achieved economic security. Therefore, all the other aspects in this category will move around this axis. That means, to agenda of economic security belongs even employment, the ability to find work, the ability to hold the job, but even the work conditions for example. This category basically speaks of the ability to materially sustain oneself, or family.

Food security is achieved when all persons by all means have physical, as well as economic access to basic food, which doesn’t mean only a sufficient amount „ready“, but access in itself: when it runs out, they can easily get new, either by growing them or buying them.

As the name suggests, health security is concerned with one’s health. In developing countries, dominant cause of death are diseases, while most of these are associated with weak nutrition and dangerous environment, such as polluted water. On the contrary, developed countries are affected by significant issues of mental health and thus we consider problems with depression, or anxiety a lack of health security as well.

Environmental security covers degradation of the local ecosystems as well as global environment. In context of developing countries, the greatest threats for environment are those, which are concerned with water or deforestation, whereas when it comes to developed countries it is primarily air pollution. Environmental security is perceived even from the global perspective – as a threat to states, or world population – but within the frames of human security agenda it is specified toward individuals. On this category, it is possible to illustrate the difference between human and state security: while global macro-level looks upon the prognosis of development and focuses on what can be done collectively to amend the environmental situation, micro-level points out how it influences the daily life of individuals.

Personal security speaks of security from physical violence. In this manner, the report of UNDP classifies threats to physical security to: threats from the state (physical torture), threats from other states (war), threats from other groups of persons (ethnic tensions), threats from individuals or gangs against other individuals and gangs (crime, street violence), threats against women (rape, domestic violence), threats against children based on their vulnerability and dependence (child abuse), threats to self (suicide, drug use) (UNDP, 1994). Basically everything, what poses a threat of physical damage to an individual.

Community security represents security we get from the membership in a certain group, be it family, community, organization, racial or ethnic group, which could provide cultural identity and set of values. Such groups can provide even practical support and members within them help each other in various ways. A community, however, according to UNDP, can have a darker side in a form of practiced cruel customs (as, for example, a female circumcision in some African communities) (UNDP, 1994). Thus, in the end, this category can actually work the opposite way.

Finally, political security is reached in societies, which value basic human rights. In other words, persons can feel politically secure in democratic states and threats to political security could be seen as violations of basic human rights (UNDP, 1994).

This concept in itself was targetted by a lot of criticisms, but it’s important to realize, that „human security“ does not replace the traditional concept of security, rather complements it. This could be actually applied to all types of deepening – they meet with criticism from people, who prefer the traditional understanding of the „security“ term and a frequent argument is that by excessive widening of its agenda, the term’s meaning depreciates.

Similar deepening of the security issues – although in this case it is a widening of the state security, not just a narrowing to a micro-level – offers a theory of researchers from The Copenhagen Peace Research Institute (COPRI), also called The Copenhagen School. Their greatest contribution in this field is the theory of securitization and related division of security into different sectors. Out of the sectors, for this article is essential societal sector in particular. Researchers from The Copenhagen School say that in association with threats to society there is a few casual topics and one of them is migration, which they describe as a situation when two bundles of people exist and one of them is overburdened, or disturbed by a strong influx of persons from the second bundle. That ultimately ends with the first bundle, or rather this community being not as it was before, since it is created by different people and thus, identity of the bundle is changed (Buzan, Wæver, de Wilde, 1998). This goes hand-in-hand with a concept mentioned in the context of societal sector and that’s the so called „horizontal competition“, which represents a situation of people from the first bundle being exposed to such high, increasing and overwhelming cultural and linguistic influence of the persons belonging to the second bundle that they are forced to changed their way of life (Buzan, Wæver, de Wilde, 1998). An alternative to the „horizontal competition“ is the so called „vertical competition“ described as a situation, when people from the first bundle stop identifying themselves as people from the first bundle due to existence of a certain higher unit, be it some integration unit or a project as Yugoslavia, or European Union. Or vice versa, they stop identifying themselves with the first bundle due to separatist projects such as Catalonia, or Quebec, which cause a dilemma for the people whether to take a more inclusive or exclusive stance toward their own identity (Buzan, Wæver, de Wilde, 1998).

According to the theory of securitization, as the referent objects (objects under an existential threat) in the societal sector can be considered any groups, communities or associations whose subjects are available to clearly identify with one another and it’s possible to determine a threat to this common identity. That means races, religious or ethnic groups, nations, clans, or tribes. It might be sexual minorities as well as groups of people with a common opinion for which they are being persecuted. Threats to these groups could be various, as we have already mentioned, it could be a persecution from the state in the case of authoritarian or totalitarian regimes, or as in the abovementioned „horizontal competition“, when a society is threatened by an influx of people with a different identity breaking the already existing one.

We dare to argue, that in a certain sense, society is a basic building unit of all state spheres be it economic, social, political, a state basically starts from the society and when it’s broken, all the state areas are affected. An extensive immigration can affect society negatively, destabilizingly and that is reflected and will always pose challenges and risks or even threats to the target state and its society. In this manner, we consider intensity of this challenges and risks to be dependent on the effectiveness of immigrant incorporation to the majority society. A level of incorporation could be considered essentially as a level of these persons‘ contribution to society and how authentically they are a part of their casual social processes, whether it is still them or they already belong among us.

2. THEORY OF ACCULTURATION AS AN INSTRUMENT FOR EFFECTIVE INCORPORATION OF INTERNATIONAL MIGRANTS

For an effective merger of immigrants to the majority society is integral that they can manage to identify themselves with cultural characteristics of the domestic population. They don’t need to necessarily accept all of the customs, traditions and social standards, it is more about not standing in opposition to common behavioural patterns and social habits to which the dominant society is used to. For an immigrant to be fully merged to society, he needs to adopt certain aspects on which the dominant society is built on. That is naturally happening – consciously or subconsciously – and it is a phenomenon which John W. Berry called acculturation. He characterizes it as a process in which an individual adopts, acquires and adjusts to a new cultural environment (Berry, 1997). In this manner, it’s necessary to emphasize the word new, since it includes a second-level learning of behavioural patterns, as opposed to so called ,,enculturation” which refers to first-level learning, mostly during childhood. Essential for us is acculturation since this process is what drives the process of incorporation.

It’s necessary to differentiate these terms. By „incorporation“ we understand a process of merging immigrants into the majority society, which can have a plethora of forms depending on relationship between these groups (oppressive, or by contrast welcoming). During acculturation, an individual adopts a new cultural environment, which doesn’t necessarily needs to end up in incorporation. It is necessary to imagine this as two streams of processes, which may or may not take place in parallel and have their own separate paths and course, although the goal remains common. Individuals of different cultures try to incorporate into a new, dominant culture by participating, or rather by engaging in various aspects of this dominant culture such as traditions. This fact alone does not necessarily involve the loss of one's own cultural characteristics. The effects of acculturation can be observed on several levels, as well as on people belonging to the dominant culture as well as on those who enter it (Berry, 1997).

At the group level, acculturation results in changes in culture, religious customs, or other social areas, while at the individual level, the acculturation process is a process of socialization by which foreigners mix values, customs, norms, or cultural attitudes and behaviours of majority culture with their own. Manifestations of this process tend to be associated with everyday behaviour, numerous changes in the psychology of individuals, and the like (Berry, 1997).

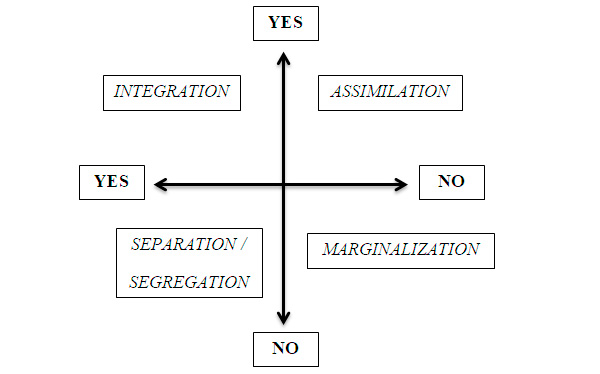

As part of his theory of acculturation, Berry created a four-part paradigm forms model, which works on a bilinear basis and in principle categorizes acculturation strategies on two dimensions, or lines.

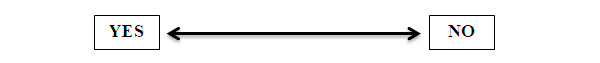

The first dimension is The Cultural Preservation and it speaks about the extent to which cultural identity and its characteristics are considered important by individuals and the extent to which its preservation is wanted. This first dimension creates a horizontal axis with the question:

,,Is it considered valuable to preserve one’s identity and characteristics?”

(Own source, 2021)

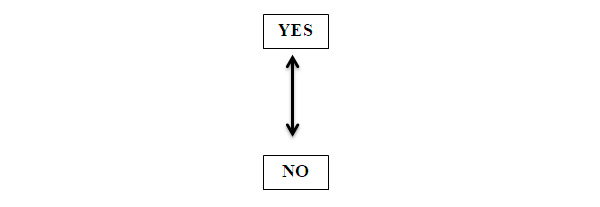

The second dimension Berry calls The Contact and Participation which speaks about the extent to which individuals should engage with other cultural groups, or whether they should remain primarily among persons from their own cultural group. The second dimension creates a vertical axis with the question:

„Is it considered valuable to maintain one’s relationship with a larger society?”

(Own source, 2021)

When these two lines intersect in the middle, based on the answers to both questions and the position of the quarter on the given scheme, we can determine one of the four Berry’s paradigmatic forms of acculturation.

(Berry, 1997)

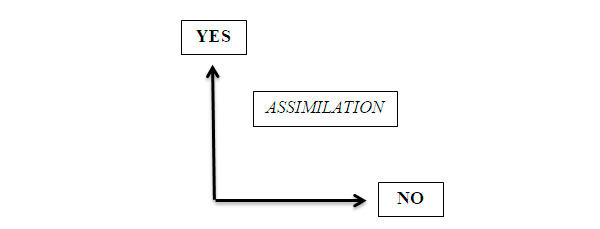

We consider answer ,,yes” to be the dominant expression of the groups, while the answer ,,no” to be the submissive expression. Assuming that individuals in a certain group do not preserve their cultural identity (submissive expression, answer ,,no” on the horizontal axis), but wish to maintain relations with the majority society (dominant expression, answer ,,yes” on the vertical axis), then we speak of assimilation. In practice, we can imagine this as a situation where immigrants have been able to incorporate into the majority society, become part of it, but without preserving their own cultural characteristics.

(Own source, 2021)

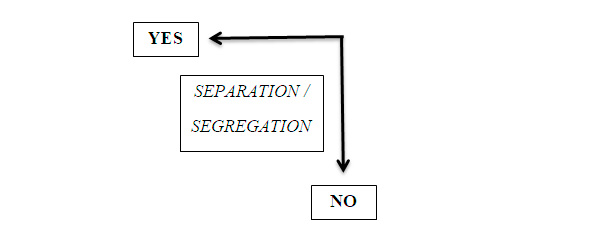

By contrast, when individuals value their culture, they do not want to give it up (dominant expression, answer ,,yes” on the horizontal axis) and at the same time do not seek interaction with other cultures, or rather with the majority culture, they directly avoid it, or are excluded by it (submissive expression, answer ,,no“ on the vertical axis), then we speak of separation/segregation.

(Own source, 2021)

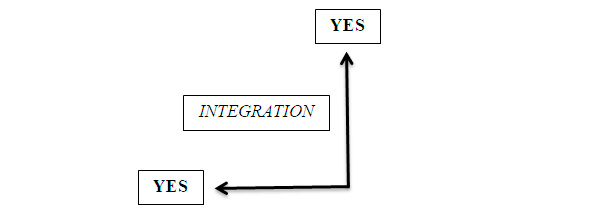

Assuming that individuals from the minority are interested in maintaining their cultural identity and at the same time interacting with other groups, or rather with the majority society, then we are talking about integration. In principle, it can be said that this is the situation that is most favourable for both parties, ideally the fairest compromise.

(Own source, 2021)

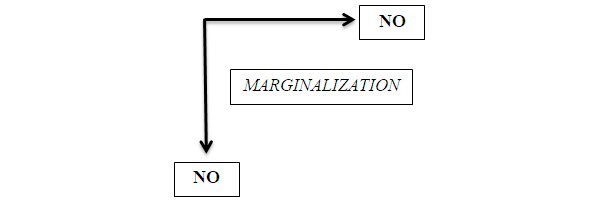

If there is little chance or little interest in preserving cultural identity (often it can be the result of oppression or coercion) and little interest in contact with the majority society (or this contact is not allowed), then we speak of marginalization. This situation will most likely not happen in democratic states.

(Own source, 2021)

However, such an understanding is based on the assumption that individual groups can choose the form or they get into it spontaneously, naturally which may not always be the case. The nature of individual forms can also change depending on whether the group seeks it or has been forced to do so. For example, if a group decides to maintain its cultural characteristics and not associate with others, we are talking about separation, but if it is pushed out by the majority society, we are talking about segregation. Also, when assimilation is voluntary, when people naturally lose ties to their cultural background, we can use the well-known term ,,melting pot”, but provided that assimilation is forced (the state/society explicitly suppresses the cultural background of the minority), the term ,,pressure cooker” is more suitable (Berry, 1997). In the context of marginalization, it is a form that a cultural group, of course, seldom chooses, and as its position on the above-mentioned scheme suggests - it is the result of attempts at forced assimilation (pressure cooker) in combination with forced exclusion (segregation). Integration, in turn, can only be freely achieved if the majority society is open and inclusive of cultural diversity, so mutual openness is a precondition - in other words, the minority society must adopt at least the core values of the majority society, while the majority society must adapt its institutions (education, health, job opportunities) to the needs of all groups living in a pluralistic society. Simply put, an integration strategy can only be followed in societies that are explicitly ,,multicultural”, or rather they seek to achieve multiculturalism and embody certain psychological preconditions - for example, widespread acceptance of the value of a society based on cultural diversity (presence of a positive ,,multicultural ideology”), relatively low levels of prejudice (minimal ethnocentrism, racism and discrimination), positive attitudes between cultural groups (no specific intergroup aversions) and a sense of identification with a larger society of all groups (Berry, 1997).

However, these issues are influenced by various factors and one of them is, for example, the appearance. Physical features that separate groups from mainstream society (e.g., Koreans in Canada or Turks in Germany) may experience prejudice or discrimination and thus be categorically against assimilation. As far as assimilation is concerned, Berry further divides it into two forms, which, when fully manifested, create the complete assimilation. These are cultural assimilation and structural assimilation (Berry, 1997). Both of these forms are already linked to the above-mentioned lines, or axes in such a way that cultural assimilation moves on a horizontal axis and is defined by a low degree of Cultural Preservation. In contrast, structural assimilation is tied to the second line, or axis and is thus defined by a high degree of Contact and Participation.

However, Milton Gordon sees differences between a culture that consists of language, customs, or values, and the social structure of society, which in turn is made up of organizations, schools, and communities (Powers, 2013). Based on this, Gordon formulated his own view of Berry's theory of assimilation by compiling essentially 3 stages of assimilation: Stage 1 - cultural assimilation - manifests itself in immigrants learning the language and customs of the majority society. Only when this stage is completed can they move to the second stage, the social structure of society - structural assimilation. He argues that migrants must be integrated first into secondary institutions such as schools or work, and only then into primary institutions such as various clubs, leisure activities, or social groups based on friendship (Powers, 2013). Interestingly, schools and work are considered secondary, but it makes sense in a discussion on the level of assimilation. Education and work are obligatory institutes, it is true that they help to connect different groups by their very nature, but there is no dimension of the free will of the individuals - in other words, they do not join work and education because they want to, but because they have to. On the other hand, leisure activities, clubs or friendships are purely optional and, as a result, speak of a higher level of interconnection of cultural groups - they are not connected because they have to, but because they want to. When structural assimilation is achieved, according to Gordon, the third stage is reached - the so-called intermarriage and thus absolute interconnection and full assimilation achieved.

Assimilation may be the most desirable situation for the receiving state, as it allows it to accept immigrants without any concessions or compromises, and in principle avoids what the Copenhagen School describes as a threat to the societal sector - that social identity begins to be lost due to the arrival of a new identity. However, this situation may not suit immigrants who do not want to give up their culture and assimilation is seldom chosen by them themselves. As mentioned above, integration is a compromise on both sides and is therefore (at least for immigrants) the most appropriate form. Integration is sometimes referred to as ,,biculturalism” (Martinez, Haritatos, 2005), and some sources suggest that this form is associated with the most favourable psychosocial outcomes of all Berry's forms, especially among young immigrants (David, Okazaki, Saw, 2009). Integrated individuals tend to be better adapted, show higher self-esteem, lower propensity for depression, socialize (Chen, Benet-Martinez, Bond, 2008) and are better able to adopt competitive principles from the different cultures to which they are exposed (Benet-Martinez, Haritatos, 2005). However, this process is not always the same. It depends on the cultural distance of the communities that come together, and this can, of course, have a positive or negative effect on the process, and this needs to be taken into account. This is also confirmed by Floyd Rudmin, who states that the degree of simplicity versus difficulty in integrating an immigrant's original and foreign culture is at least partly determined by the degree of similarity (actual or perceived) between the original and foreign culture (Rudmin, 2003). If ethnicity is a constant, knowing the language of the destination country is a great advantage for immigrants over those who face a language barrier. For example, Jamaicans will face less discrimination or acculturation stress than Haitians (Schwartz, Unger, Zamboanga, Szapocznik, 2010). Also, as mentioned above, differing ,,at a glance” can potentially open up a new level of barriers and, last but not least, mental cultural traits, such as religion, which may prevent them from participating in certain social activities typical of the target country. If a Slovak tries to integrate into the Czech Republic, he will probably face less resistance than someone from Syria. For this reason, Berry's model also met with criticism - he was criticized for trying to apply one size to all migrants, regardless of their individuality (Rudmin, 2003).

In order to fully understand acculturation, it is necessary to fully understand the interaction context in which it takes place, and by this context we understand the characteristics of individual migrants, groups or countries of origin, socio-economic status and resources, country and local community in which they settle and also fluency in the language of this country (Schwartz, Unger, Zamboanga, Szapocznik, 2010), these are all factors that fundamentally influence the acculturation process and cannot be ignored. At present, public discourse seeks to avoid discrimination based on racial or ethnic characteristics, as this can often bring with it some form of discrimination, but for the process of acculturation or incorporation as such, it is integral. Schwartz and his psychology colleagues cite two terms that are relevant to acculturation and require clarification and definition, namely ,,ethnicity” and ,,culture”, because so many current migrants to the United States or other Western countries come from a non-European background (Steiner, 2009; C. Suárez-Orozco, Todorova, 2008), ethnicity has become an integral aspect of the process of acculturation and reception of migrants - where ethnicity refers to membership in a group that maintains a specific cultural heritage and set of values, beliefs and customs (Schwartz. Unger, Zamboanga, Szapocznik, 2010, 240). And since acculturation in practice means cultural change, it is necessary to define the content of the term ,,culture” as shared meanings, understandings and references maintained by a group of people (Shore, 2002; Triandis, 1995). Floyd Rudmin also acknowledges that the similarity between the culture of the destination state and the culture of immigrants helps to define the difficulty of the acculturation process as the migrant adapts to the culture of the destination country (Rudmin, 2003). Schwartz and colleagues also add that ,,permutations between language, ethnicity and cultural similarity, among other factors, affect the ease or complexity associated with the acculturation process. For example, a white, English-speaking Canadian who moves to the United States will most likely have much less work to do with acculturation than an indigenous migrant from Mexico or Central America. This is not only because of the common language shared by the United States and Canada, but also because of other cultural similarities (e.g. similar orientations towards individualism versus collectivism) and the ability of white migrants to merge with the American mainstream (Schwartz, Unger, Zamboanga, Szapocznik, 2010, 240).

Last but not least, the types of individual migrants need to be taken into account in acculturation, as the acculturation options available to people may vary depending on the circumstances of their migration (Steiner, 2009). Berry divided migrants into 4 types: voluntary immigrants, refugees, asylum seekers, and sojourners (Berry, 2006). He describes voluntary immigrants as individuals who leave their homes at their own discretion in order to find employment, economic opportunities, get married, or join family members who have already immigrated before them. According to him, refugees are those who have been involuntarily displaced by war, persecution or natural disasters and are relocated to a new country. He understands asylum seekers as those who voluntarily seek refuge in a new country for fear of persecution or violence. Finally, sojourners travel to a new country only for a limited period of time and for a specific purpose with the intention of returning to their home countries as soon as the period expires - these are international students or seasonal workers (Schwartz, Unger, Zamboanga, Szapocznik, 2010). We dare to disagree with Berry's classification, as we consider the category of refugees and asylum seekers as, in the context of the intentions with which they found themselves in the destination country, the same. Also, to claim that asylum seekers seek refuge ,,of their own free will” is highly erroneous, and we can argue that there is as much free will in a given decision as is in the case of a refugee decision to escape because of war. We would also like to say that for the majority society or the culture of the destination country, it is the same if an asylum seeker from Syria or a refugee from Syria is in it, not to mention that the two categories are often the same. The same is true for voluntary immigrants and sojourners, for whom we also consider the influence of their motivation to come is the same on the acculturation process. So should we establish only two out of these four categories - voluntary and involuntary - we can agree not only with Berry but also with other authors writing that migrants who are perceived as contributing to the economy or culture of the host country - such as volunteers, doctors or other professionals - can be welcomed with open arms, while refugees/asylum seekers, i.e. the involuntary ones, can be seen as a burden on the resources of the host state (Steiner, 2009) and have a better chance to face discrimination (Louis et al., 2007). This is only logical, because in the case of voluntary migrants we can expect that since they are interested in employment and actively contribute to the destination state, they are in some way prepared for it and want to be active in it, while involuntary migrants are forced to leave unexpectedly to the receiving state and must be actively involved in it, as they have no choice. In such a case, it is natural that the acculturation process is hampered and that migrants who are rejected or discriminated against may have more difficulty adapting and may refuse to adopt the customs, values and identity of the destination state (Rumbaut, 2008). And in such situation, we face the fact that risks or threats to the security of the receiving states become significant, because there is neither integration nor assimilation, but most probably separation and emergence of parallel cultures within a single demarcated area. Such a situation does not offer migrants the opportunity to connect with the majority society and become acquainted with it, to adopt its behavioural patterns - it pushes them to the margins, thus creating a settled community of people who stay ,,among their own”, setting an undesirable precedent for potential other migrants from this ethnicity or cultural background, who will automatically tend to this settled community rather than the majority society. (Hreha – Rajda, 2019) Even the children of such migrants may not be accepted as full members of the host society, suggesting that accultural stressors and discrimination may persist beyond the first generation (Suárez-Orozco et al., 2008). And this brings us back to the situation described by the Copenhagen School in the societal security sector, when it spoke of the conflict between the identities of two different unions. Ole Wæver also emphasizes this in his study, where he defines societal security as ,,the defense of identity against a perceived threat, or more precisely, the defense of a community against a perceived threat to its identity” (Wæver, 2008: 581).

The theory of acculturation offers us a closer look at the processes that take place in society after the arrival of new cultures. The societal security sector - unlike the concept of human security - is not concerned with the protection of ,,human life” as such, but, as Wæver writes above, with explicitly identitary aspects of society. A person is, of course, the basic building unit of society, and therefore his absence should naturally pose an existential threat to it, but as Wæver puts it, although in situations such as plague, famine, or war, which is not aimed at killing civilians, the collective survival of identity may be endangered, but we cannot interpret the deaths of the individuals in this way. In the case of the Holocaust or other ethnic cleansing policies, of course, this is possible, but when an individual loses his life, the loss of identity is usually not at the center of this view. Not unless a given death occurs in combination with a perceived rivalry with another identity (Wæver, 2008). Most people are more afraid of losing their lives than the fact that their demise contributes to the demise of the collective's identity, but this is only true if their life as such is targeted, not their identity. More graduate processes of negative development in demography tend to be perceived more dramatic and are more likely to be perceived as a collective security issue and do not necessarily need an aggressor to be securitized (Wæver, 2008).

Different societies have different weaknesses depending on how their identity is constructed. If one's identity is based on separation, distance and a certain form of solitude, even a small mixture with foreigners can be perceived as problematic, and also states with a small population are vulnerable to communities with higher fertility rates. Acculturation as a process in which one acquires a foreign culture (usually a majority one) and adapts to a new cultural environment can be a useful tool for understanding the realities of merging immigrants into majority society. The high intensity of the negative consequences of immigration tends to be the result of the inefficient incorporation of immigrants, as they do not become one society with the dominant one, and there is a certain form of competition in the dynamics of their relationship. All communities in such situation are pulling their own end of the rope, and acculturation as a theory of these processes of merging can make them more effective, if applied correctly.

REFERENCES

- General Assembly (2012): Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 10 September 2012. 2012. [online]. [cit.2021.20.01]. Available at:

- Gregoratti, C. (2021): Human Security. 2021. [online]. [cit.2021.20.01]. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/human-security

- Hreha, L. – Rajda, Z. (2019)Zákonná úprava v boji proti súčasnému fenoménu extrémizmu. In: Národnáa medzinárodná bezpečnsoť 2019, Liptovský Mikuláš : AOS LM 2019, ISBN 978-80-8040-5823, p. 155-16

- Ivančík, R. (2012): Teoreticko-metodologický pohľad na bezpečnosť. In: Vojenské reflexie. Vol. 7, No. 1/2021, pp. 38-57. ISSN 1336-9202.

- Ivančík, R. – Baričičová, Ľ. (2020): Gnozeologické pramene skúmania bezpečnosti v 21. storočí. In: Policajná teória a prax. Vol. 28, No. 2/2020, pp. 20-43. ISSN 1335-1370.

- Jolly, R., Ray, D. B. (2006): The Human Security Framework and National Development Reports: A Review of Experiences and Current Debates. 2006. 38 p. [online]. [cit.2021.20.01]. Available at:

- Rudmin, F. W. (2003): Critical History of the Acculturation Psychology of Assimilation, Separation, Integration, and Marginalization. In: Review of General Psychology. 2003. p. 3-37. [online]. [cit.2021.20.01]. Available HERE

- Schwartz, S. J., Unger, J. B., Zamboanga, B. L., Szapocznik, J. (2010): Rethinking the Concept of Acculturation: Implications for Theory and Research. In: American Psychologist, 65(4). 2010. p. 237-251

- Todorović, B. Trifunović, D. (2020): Security science as a scientific discipline - technological aspects. In: Security Science Journal. Vol. 1 No. 1 (2020). p. 9 -20

- United Nations Development Programme (1994): Human Development Report 1994. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1994. 226 p. ISBN 0-19-509170-1

- United Nations Trust Fund For Human Security (2021): What is human security? 2021. [online]. [cit.2021.20.01]. Available at:

- Wæver, O. (2008): The Changing Agenda of Societal Security. In: Globalization and Environmental Challenges. Hexagon Series on Human and Environmental Security and Peace, vol. 3. New York: Springer. 2008. p. 581-593. ISBN 978-3-540-75977-5

Prof.dr Rastislav Kazansky

Assoc. prof. PhDr. Rastislav Kazansky, PhD., MBA Professor of Department of Security

Studies, Faculty of Political Sciences and International Relations, Matej Bel University,

SLOVAKIA

Review Paper

- Received: November 3, 2020

- Accepted: December 9, 2020