Author: Jack Gill

Abstract: This paper analyses the motives of the Kremlin’s ongoing war in Ukraine, the Russian Federation’s significant geopolitical pivot away from Europe and the consequences thereof for Ukraine and the rest of Europe. In particular, the strategic importance of the Sea of Azov for the Kremlin’s access to the oceans is considered. After providing this context, the paper explores some possible ways in which Ukraine could join the European political-economic and security structures, and under what conditions, including by achieving security guarantees from the United States, similar to South Korea and Israel, as well as by declaring military neutrality. Thereafter, the paper examines the potential challenges to Ukraine’s redevelopment given the geopolitical circumstances and provides some conclusions.

Keywords: Ukraine; Russia; security; geopolitics; redevelopment.

Introduction

The course of Ukrainian history changed fundamentally in 2022. After Russia’s invasion of large parts of the country, Ukrainians’ steadfast resistance to Russian brutality and unmatched commitment to Western integration has made it beyond doubt that Ukraine’s future lies politically in Europe and not in Russia’s sphere of influence. The damage – not only physical but also psychological and sociological – wrought by the Russian military in Ukraine will make it difficult to reconcile the two sides in the years to come. Nevertheless, the Ukraine question – in other words, its future geopolitical and security status – is the primary issue of international relations of our time, and when viewed from a geopolitical perspective, taking into account great power interests and strategies and the historical outcomes of countries that faced and continue to face similar challenges to Ukraine, a wider picture begins to emerge in which Ukraine does not appear entirely unique. Many clever solutions have been devised for such countries with difficult (and larger) neighbours that challenge their sovereignty. As such, only by viewing Ukraine – and, indeed, its smaller but like-minded neighbours Moldova and Georgia – through such a wider lens can we understand the interests of all parties and develop inspired solutions to this geopolitical crisis. But in order to understand Ukraine’s difficulties, we must first examine Russia’s new “grand strategy”.

Putin’s Grand Strategy

The current conflict we are witnessing in Ukraine can be seen through a much broader global geopolitical lens. With Russia’s invasion and the imposition of crippling sanctions by most Western countries, the Kremlin is conducting a great pivot away from Europe towards Asia and the Middle East. As Europe no longer holds the strategic importance for today’s Russian Federation that it once did for the Soviet Union during the Cold War, the Kremlin is diversifying its economic and political partnerships with other global players, most notably by coupling with the People’s Republic of China (PRC).

As the next step in President Putin’s grand plan for global power projection, like for any other empire in history, ensuring year-round secure access to the world’s oceans is of critical importance. Although Russia has vast coastlines, its coasts along the Arctic Ocean are frozen for too much of the year to be relied upon for primary ports, while Vladivostok on the Sea of Japan is so far by land from the Russian heartlands in Eastern Europe that it also can only play a smaller role in Russian logistics.

This leaves the Baltic Sea and the Black Sea, which historically have provided Russia with its most important sea access. With the pivot away from Europe (and therefore also the North Atlantic), we have seen a significant decline in the strategic importance Russia places on the Baltic Sea, which, with the accession of Finland and (soon) Sweden to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), will soon become a largely internal NATO sea. A global power projection strategy is thus no longer feasible if the Baltic Sea were to be the main hub of the Russian navy and shipping. As a result, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine (both in 2014 and 2022) could be viewed as the Kremlin putting all of Russia’s resources into securing – permanently – Russia’s unrestricted access to the world’s oceans through the Black Sea. And while Russia invaded Crimea in 2014 to secure Sevastopol and the peninsula as a whole, capturing these territories was not enough.

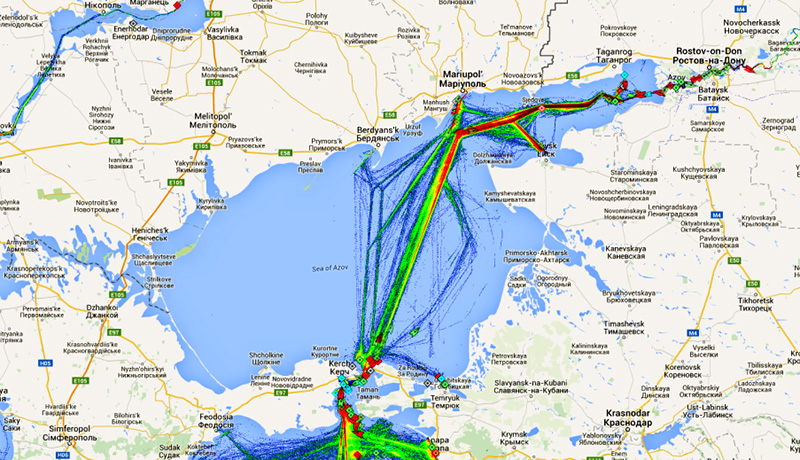

Although Russia already has a coastline along the Black Sea, it has only one large port with direct access – Novorossiysk, Russia’s largest cargo port. But equally weighty for Russia is control of the Sea of Azov – a smaller sea, on the western half of which lie the Ukrainian regions (oblasts) of Kherson and Zaporizhzhia. As the Sea of Azov is the shallowest in the world with a maximum depth of just 14m, all shipping through the sea to the Russian port at Rostov-on-Don and onwards to the Volga River and Caspian Sea must sail through Ukrainian territorial waters, close to the Ukrainian city of Mariupol. Moreover, to access the Black Sea from the Sea of Azov, a ship would need to sail through the tight Kerch Straight, which separates Crimea from southern Russia. If Ukraine had kept control over Crimea and joined NATO, then, like in the Baltic Sea, Russian ships would have to tiptoe along the Russia/NATO maritime border and would undermine Putin’s strategy.

Additionally, because Turkey controls the straights of the Bosphorous ¬– the only entrance or exit to the Black Sea – maintaining close relations with Turkey must also remain a very high priority for the Kremlin, and Turkish President Recep Erdoǧan has courted the Kremlin on a number of strategic issues, including increasing economic ties in contrast to most European countries, as well as positioning Turkey as a neutral party in the conflict despite the country’s membership in NATO.

By taking control over much of the Ukrainian regions of Kherson and Zaporizhzhia, the Kremlin has likely achieved the main strategic goal of its war in Ukraine. It must now hold on to them. Whether the Ukrainian military can launch a successful counteroffensive to reconquer these territories in addition to Crimea and Donbas remains to be seen. In any case, by invading the Ukrainian territories around the Sea of Azov, Russia is attempting to secure this vital ocean access for the years to come. Ukraine and especially Crimea joining NATO would, so to speak, be checkmate to NATO, as Russia would have only the remote port of Vladivostok and the frozen port of Murmansk as its primary ocean ports that are not in extreme proximity to NATO.

Figure 1: Sea of Azov Traffic Density Map (23/07/2023). Source: Shiptraffic.net http://www.shiptraffic.net/2001/04/sea-of-azov-ship-traffic.html

Figure 2: Sea of Azov Maritime Border Map. Source: http://opennauticalchart.org/

Security Guarantees for Ukraine

As it cannot be assured that Ukraine will defeat Russia on the battlefield, let alone reconquer all of its lost territories, foreseeing Ukraine’s redevelopment in the context of current Russian aggression and likely future Russian malevolence, Ukraine will certainly need powerful security guarantees at the end of the conflict to ensure its stable reconstruction. In this regard, we need not necessarily look to Europe to provide us with examples of successful security guarantees for countries in difficult geopolitical situations. Indeed, other countries around the world, most notably Israel and South Korea, serve as far more relevant examples of the geopolitical environment wherein Ukraine finds itself. With hostile and threatening neighbours, Israel’s and South Korea’s external security is guaranteed primarily through extensive bilateral military agreements with the United States.

Israel, for example, has extensive foundational agreements on defence and security with the United States, including an “Agreement relating to mutual defense assistance” (1952). In the case of South Korea, the Mutual Defense Treaty Between the United States and the Republic of Korea, signed on 1 October 1953, stipulates that the two countries

“will consult together whenever, in the opinion of either of them, the political independence or security of either of the Parties is threatened by external armed attack. Separately and jointly, by self help and mutual aid, the Parties will maintain and develop appropriate means to deter armed attack and will take suitable measures in consultation and agreement to implement this Treaty and to further its purposes.”

Given the economic and developmental success of South Korea since the 1950s, it is clear that the protection offered by the US played a key role in deterring its neighbours from launching full-scale invasions, allowing for stable economic and democratic development. For Ukraine, the post-war settlement will certainly involve the US, and significant security guarantees on the part of the US would be a major gain for Ukraine.

Military Neutrality

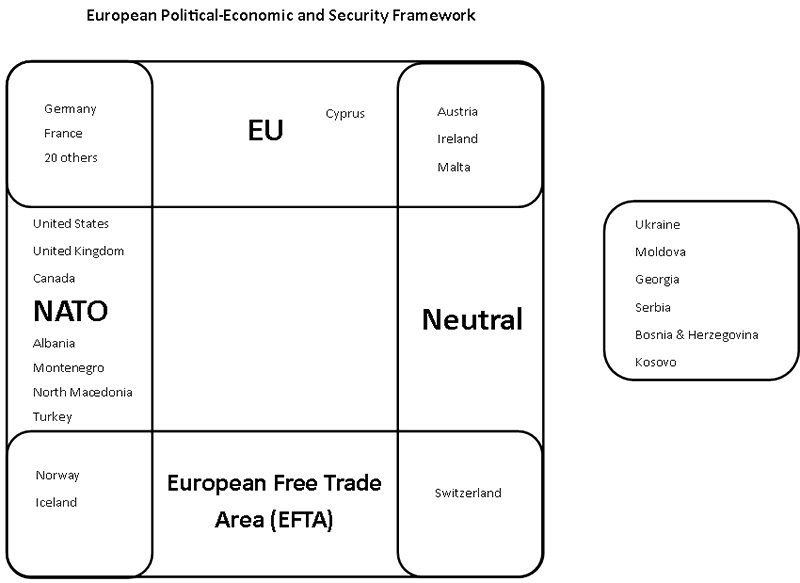

Key to the settlement of the Second World War in Europe was the status of two countries in particular – Austria and Finland – which occupied strategic areas and decided to become neutral. For Finland, which had a significant land border with the USSR, neutrality was the only option given its strategic location at the side of the Gulf of Finland, a key entry for the Soviet navy to the open seas and the mouth of Russia’s second-largest city, St Petersburg. In 1948, Finland signed the “Agreement of Friendship, Cooperation, and Mutual Assistance” with the Soviet Union, which allowed Finland to maintain its liberal democratic system while guaranteeing that “no third party would exploit Finland’s territory against the Soviet Union”. This was known as the Paasikivi Policy. Preventing Finland from joining NATO was a major success for Soviet foreign policy. By contrast, Austria occupied a very different but equally important location in Central Europe. On the border between NATO and the Warsaw Pact, Austria broke the NATO front between West Germany and Italy. After being reconstituted as a neutral country in 1955, the country also became a key meeting point for Eastern and Western officials and home to many international organisations, including some United Nations (UN) institutions and the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE). For nearly half a century during the Cold War, neutrality allowed Austria and Finland to develop nonetheless in a Western direction. Both countries became highly economically successful and free democracies. Where countries like Austria differ from Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia is that although they are not inside NATO, their security is guaranteed by their internationally recognised military neutrality, which has allowed them to join the European political-economic framework, i.e. either the European Union itself or the European Free Trade Area (EFTA). However the ongoing war in Ukraine ends, by declaring its own military neutrality, Ukraine (as well as Georgia and Moldova) could make a large step into the western structures, outside of which they are currently located. Neutrality could offer these countries a geopolitical stability unlike anything they have had previously, allowing for increased foreign investment and stabler democratic development, while also demonstrating that they will not become a threat to the Kremlin by joining NATO.

Figure 3: European Political-Economic and Security Framework. Credit: Author.

Another Way into Europe

Given the similarities in the challenges Ukraine faces with its fellow post-Soviet states of Moldova and Georgia, namely their post-communist transition and democratisation, as well as their internal breakaway territories, proximity to Russia (in the case of Ukraine and Georgia) and efforts to join the Euro-Atlantic security architecture, Ukraine, Georgia and Moldova are sometimes referred to as the Association Trio (A3) thanks to their signing association agreements with the EU. As a collective, the A3 represent an altogether different challenge to European integration than other groupings of former communist countries, such as the Baltic States, the Visegrad 4 or the Western Balkans 6. Because of the A3’s – and especially Ukraine’s – geostrategic location and their historical importance to Russia, as well as their ongoing issues with breakaway territories, their future is a geopolitical challenge unlike any other in Europe. Joining NATO is not an option for the A3 in the short or medium term due to their lack of territorial integrity and the perceived risk that this would pose to the Kremlin. Instead, their first step to join the European political-economic and security framework could be to become neutral and, upon satisfying the EU’s Copenhagen Criteria, thereafter join the EU or the European Free Trade Area (EFTA). The latter could only happen when the former is complete. To aid in this process, the creation of a “European Grouping of Neutral States”, including Switzerland, Austria, Ireland and Malta could offer encouragement and support to prospective neutral states in Europe, representing a real alternative path to European integration than the traditional goal of both EU and NATO membership.

Conclusion

Turning to Europe today, we see a similar need to find a status quo that suits all sides, and just like in the aftermath of the Second World War, military neutrality may again provide the best solution. On the other hand, with credible and far-reaching security guarantees from the US and the EU, Ukraine, like Israel and South Korea, would be in a much better position to develop economically and politically, without necessarily becoming explicitly neutral. Though many believe the Western alliance should arm Ukraine until it somehow achieves victory over the Russian war machine, the final settlement of the conflict will have to take into account Russian as well as Ukrainian interests. When we look at history, the post-war settlement in Europe after 1945 reflected the geopolitical interests of two great powers, the United States and the Soviet Union. Similarly, the outcome of this war will be a compromise unlikely to thrill anyone, central to which will be the military status of Ukraine as well as the Sea of Azov and the Ukrainian lands on the western side thereof. Nevertheless, based on the arguments laid out in this paper, some useful conclusions may be drawn.

1. Russia’s pivot away from Europe towards other parts of the world means that we are entering a new period of geopolitics with regard to Russia. Central to the Kremlin’s new strategy is security in the Black Sea and especially the lands on the other side of the Sea of Azov, namely the Kherson and Zaporizhzhia oblasts. Whatever the outcome of the conflict, the new security arrangement of Ukraine will have to consider Russian interests in this area.

2. There are a number of ways to guarantee Ukraine’s security in the aftermath of the ongoing war with Russia. This paper explored two possible situations regarding Ukraine’s future military status: far-reaching security guarantees offered especially by the United States (similar to South Korea) as well as the European Union, and/or a military neutrality arrangement that does not preclude Ukraine from joining the European Union. Due to the sheer size of Ukraine, its complex history and enormously strategic location, solving the Ukraine question is the geopolitical challenge of our time in Europe. Its path into the European political-economic and security framework could be unique to Ukraine, but solving it as soon as possible is the best guarantee of European security for the foreseeable future.

Index:

1. Volume of cargo handled in Russia in 2022, by largest port (in million metric tons). Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1023550/russia-cargo-throughput-by-port/#:~:text=The%20Russian%20seaport%20Novorossiysk%2C%20located,million%20metric%20tons%20of%20cargo. Accessed 25/07/2023.

2. “Sea of Azov. Britannica.com. https://www.britannica.com/place/Sea-of-Azov. Accessed 24/07/2023.

3. “Erdoğan: I have a ‘special relationship’ with Putin — and it’s only growing”. Politico. 19 May 2023. https://www.politico.eu/article/turkey-special-relationship-russia-grow-recep-tayyip-erdogan-valdimir-putin//. Accessed 25/07/2023.

4. Agreement relating to mutual defense assistance. Exchange of notes at Tel Aviv July 1 and 23, 1952. Entered into force July 23, 1952. 3 UST 4985; TIAS 2675; 179 UNTS 139. U.S. Department of State. Treaties in Force.

(p.218). https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/TIF-2020-Full-website-view.pdf

Article II, Mutual Defense Treaty

Between the United States and the Republic of Korea; October 1, 1953. https://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/kor001.asp

“The Paasikivi Policy

and Foreign-Policy Thinking”. https://web.archive.org/web/20040613052725/http://www.paasikivi-seura.fi/society/paasikivipolicy.htm. Accessed 25 July 2023.